Long before the telescope reshaped astronomy, when European star charts were still sparse and speculative, Chinese astronomers were looking up at the heavens with a determination and precision that continues to astonish scientists today. For more than two millennia, they recorded celestial events—comets streaking across the sky, eclipses casting sudden shadows, planets aligning in celestial choreography, and mysterious “guest stars” that appeared suddenly, lingered in stillness, then faded into obscurity.

These guest stars—transient luminous objects—have intrigued generations of astronomers. Some turned out to be novae or supernovae; others remain unidentified, buried in historical ambiguity. But with every ancient record lies a potential treasure: evidence of astronomical phenomena that can be traced, analyzed, and matched with modern astrophysical data. One such tantalizing mystery, first documented in 1408 CE during the Ming Dynasty, has puzzled experts for centuries—until now.

A breakthrough led by Boshun Yang and his team at the University of Science and Technology of China has shed new light on this 600-year-old event. Their research, recently posted on the arXiv preprint server, offers compelling evidence that the so-called guest star of 1408 was not merely a curious entry in an imperial almanac—it was a real astronomical nova, and its story has finally been told.

The Guest Star That Wouldn’t Leave

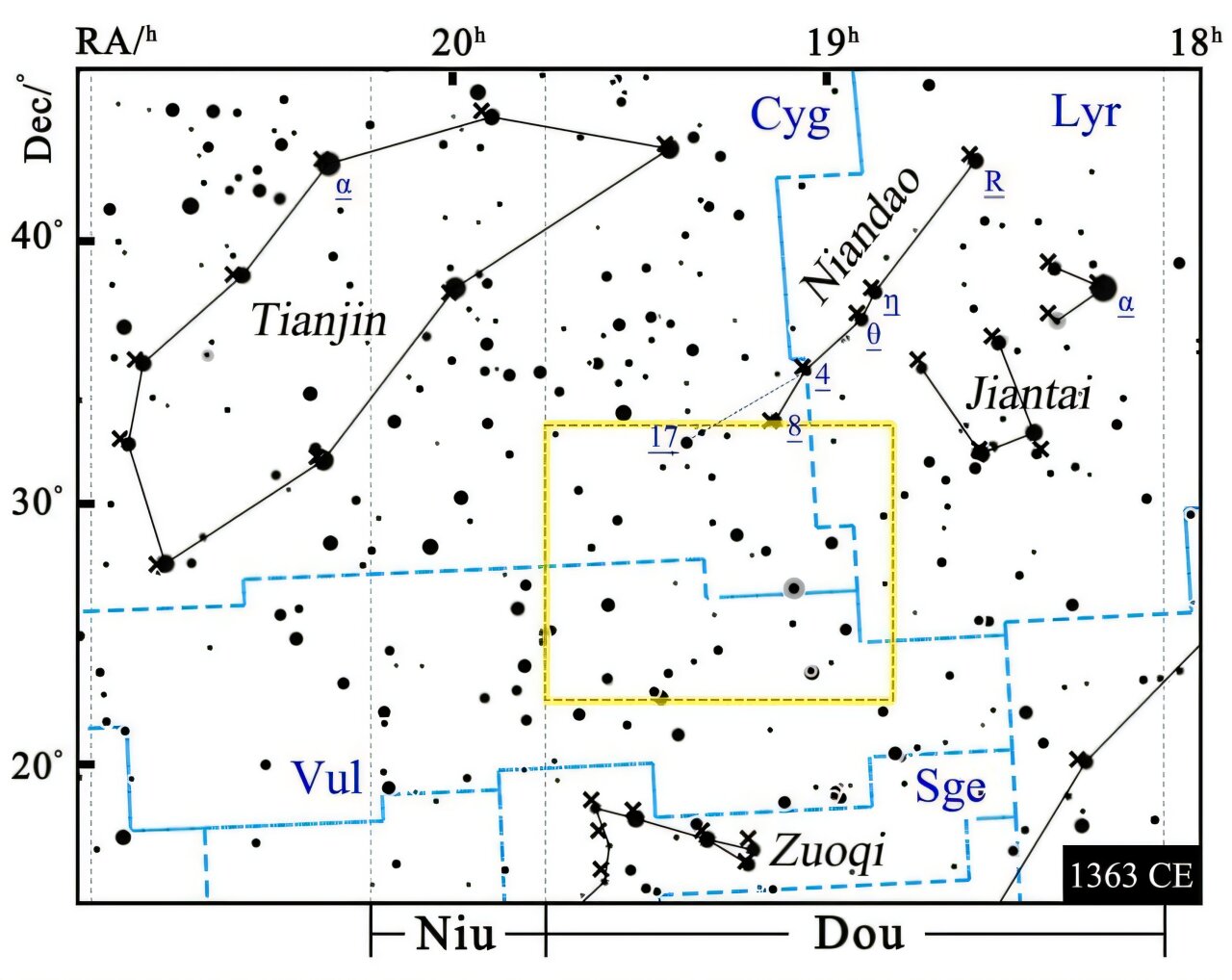

The 1408 event wasn’t flashy in modern terms, but for the stargazers of the Ming court, it was unusual enough to be preserved in official documents. On an October night in that year, a luminous yellow object appeared in the sky near the “Niandao” asterism—a star grouping now located within the modern constellations of Cygnus and Vulpecula.

The object stood out immediately. It didn’t move like a comet. It didn’t flicker or dart across the sky. Instead, it stayed put—serenely, steadily glowing—for more than ten days. Observers described it as bright, yellow, and strangely calm. In an age when celestial phenomena were often interpreted as omens from the heavens, the language used to describe this one was curiously positive.

That detail was not lost on astronomers. Describing a guest star as “pure yellow,” “smooth and bright,” and “stationary” seemed to speak not only to the nature of the object, but also to the political climate of the time. Court astronomers were responsible not only for identifying stars but also for filtering their descriptions in ways that would not displease the emperor. It was a dance between science and diplomacy, where a poorly worded report could mean disaster for the astronomer rather than the empire.

Yet for all its delicacy, the record was specific. And that specificity, when revisited by modern astrophysicists with access to new data and sharper models, turned out to be a scientific goldmine.

Reading the Sky in Ancient Chinese

Identifying historical astronomical events is far more than a matter of translation. Ancient Chinese star charts used different constellations, different coordinate systems, and deeply symbolic terminology. The Niandao asterism, for example, is not something that maps directly onto our familiar Western constellations. Understanding what it meant required scholars to reconstruct the celestial worldview of a culture where the stars were not just points of light but active participants in human affairs.

Over the centuries, many guest star observations were dismissed as either legendary or exaggerated. Some lacked enough data to draw firm conclusions. But Yang and his colleagues were determined to revisit the 1408 report with fresh eyes—and a new piece of the puzzle.

That piece came in the form of a previously overlooked primary document, a detailed memorial written by court scholar Hu Guang shortly after the event was observed. Unlike the brief, summarized entries in traditional star catalogues, Hu’s report was a vivid and formal narrative prepared for the imperial court. It gave context, description, and tone—crucial for interpreting whether the guest star had been a comet, a nova, or something else entirely.

The Imperial Memorial: A Glowing Description

Hu Guang’s memorial described the object as “as large as a cup,” which in pre-modern Chinese astronomy typically referred to angular size—a tricky descriptor, but one that signals unusual visibility. More importantly, it described the guest star’s light as “pure yellow” and “smooth and bright”, with no motion, no erratic behavior, and a visible presence that lasted for over ten days.

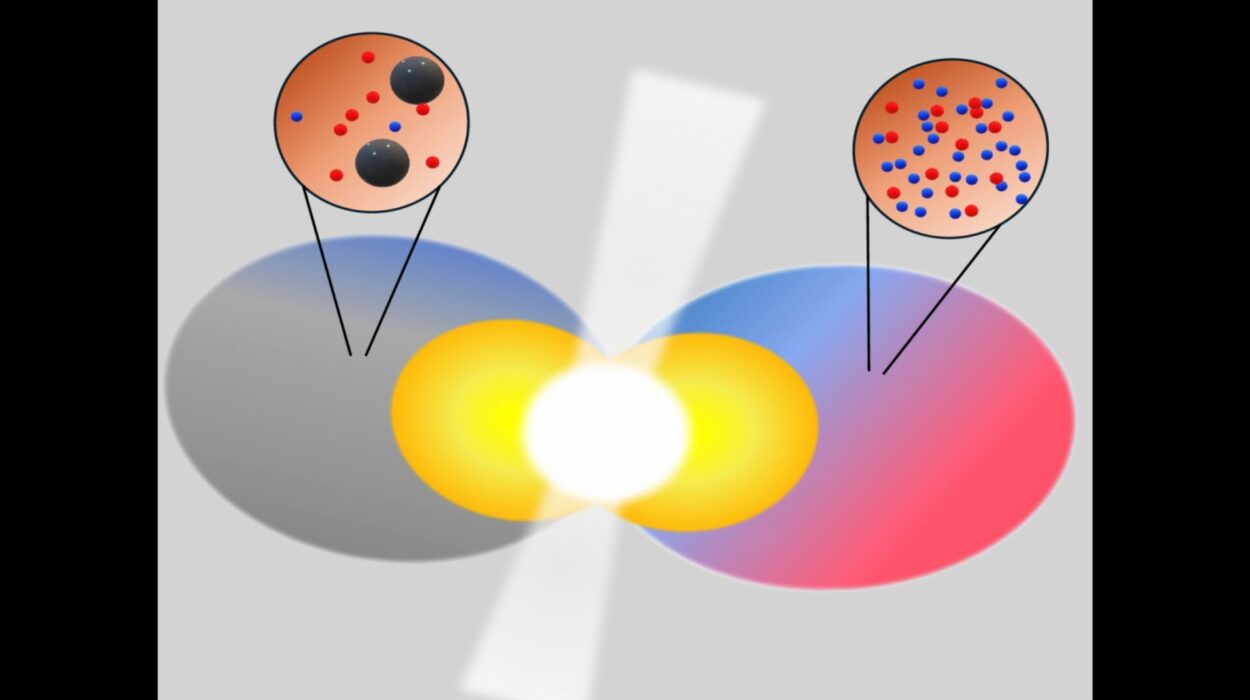

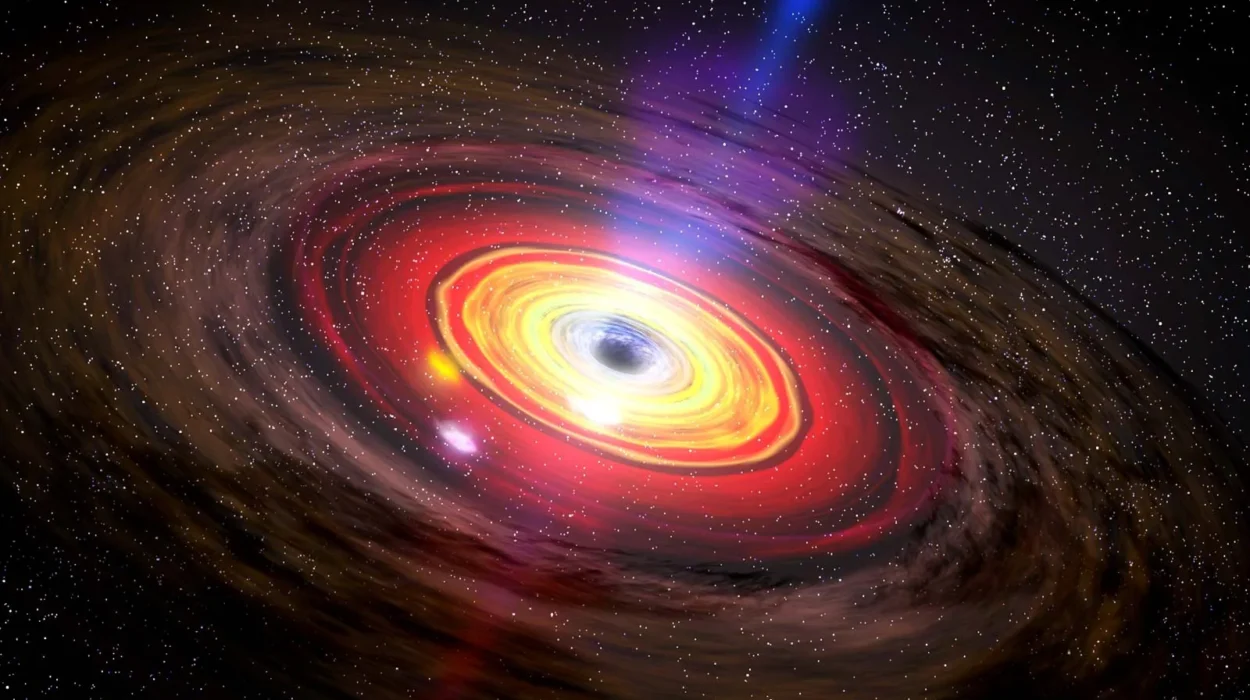

To modern astrophysicists, these characteristics are unmistakably suggestive of a nova—a powerful thermonuclear explosion on the surface of a white dwarf in a binary system. Unlike supernovae, which are catastrophic stellar deaths, novae are more like celestial hiccups: brilliant and dramatic, but ultimately survivable for the star involved. Their light curves can vary—some flare and fade within days, others plateau in brightness before dimming over weeks or months.

What makes this nova unique is its exceptional stability. Its brightness did not fluctuate noticeably during the observation period. It remained “calm,” as the records noted. That plateau-like light curve is characteristic of a specific subclass of novae—possibly a slow nova, which can remain near-peak brightness for extended periods.

Color and Culture: The Yellow Light

The color of the object—described clearly as “yellow”—has also fueled rich scientific discussion. Ancient Chinese observers used a limited color vocabulary, and the word for yellow carried cultural weight. It was the color of royalty, prosperity, and virtue—terms that reflected favorable interpretations. In many astronomical records, unpleasant or frightening events were often described as dark, red, or spiky—linguistic codes meant to signal disorder or danger.

The choice of “yellow” in the 1408 record is thus telling. It could reflect both the star’s actual appearance and the court astronomers’ desire to frame the event positively. Regardless, the ability to discern color in a stellar object implies high brightness. Typically, only stars of magnitude 2 or brighter show distinct color to the naked eye. This detail, combined with the object’s sustained visibility and ceremonial significance, supports the idea that the 1408 event was a bright, long-lasting nova—perhaps reaching as bright as magnitude -1 or -2, rivaling Jupiter in the night sky.

From Guest Star to Nova: The Astronomical Forensics

Matching a historical observation to a known astrophysical source is no easy task. But Yang’s team dug deep into star catalogs and modern sky surveys, looking for lingering signs of a stellar outburst that could correspond to the 1408 guest star.

They focused on the region near Cygnus and Vulpecula, the general location specified in the historical records. Today, this area is rich with potential nova candidates, but one target stood out: V606 Vulpeculae, a nova-like system that has shown behavior matching the slow-brightening and prolonged decay typical of classical novae.

Spectral analysis, positional alignment, and theoretical modeling all point to V606 Vul as a prime candidate. While astronomers can’t yet confirm this conclusively—novae don’t leave behind the same dramatic remnants as supernovae—the evidence is strong enough that the 1408 event can now be considered a likely nova with high confidence.

Why It Matters: The Past Illuminating the Present

So why does identifying a 600-year-old guest star matter? It matters because novae are still poorly understood in many ways. Their frequency, luminosity profiles, and aftermaths are areas of active research. Historical observations offer a rare baseline—independent data points that help calibrate our models and confirm our theories.

The 1408 event also reminds us that pre-modern societies were not merely passive observers of the cosmos. Chinese astronomers, in particular, recorded the sky with a rigor that rivals modern scientific practice. Their data, though filtered through cultural and linguistic lenses, remain astonishingly valuable. When these records are matched with modern telescopic data, they don’t just confirm ancient wisdom—they expand the timeline of observable celestial behavior, extending the reach of astrophysics into centuries long before the invention of photography or spectroscopy.

Moreover, this case underscores the interdisciplinary magic of modern science. Solving the mystery required not just astronomy, but also sinology, history, linguistics, and cultural anthropology. It was a detective story that spanned six centuries, where old paper and new algorithms worked side by side.

Beyond 1408: Charting the Historical Sky

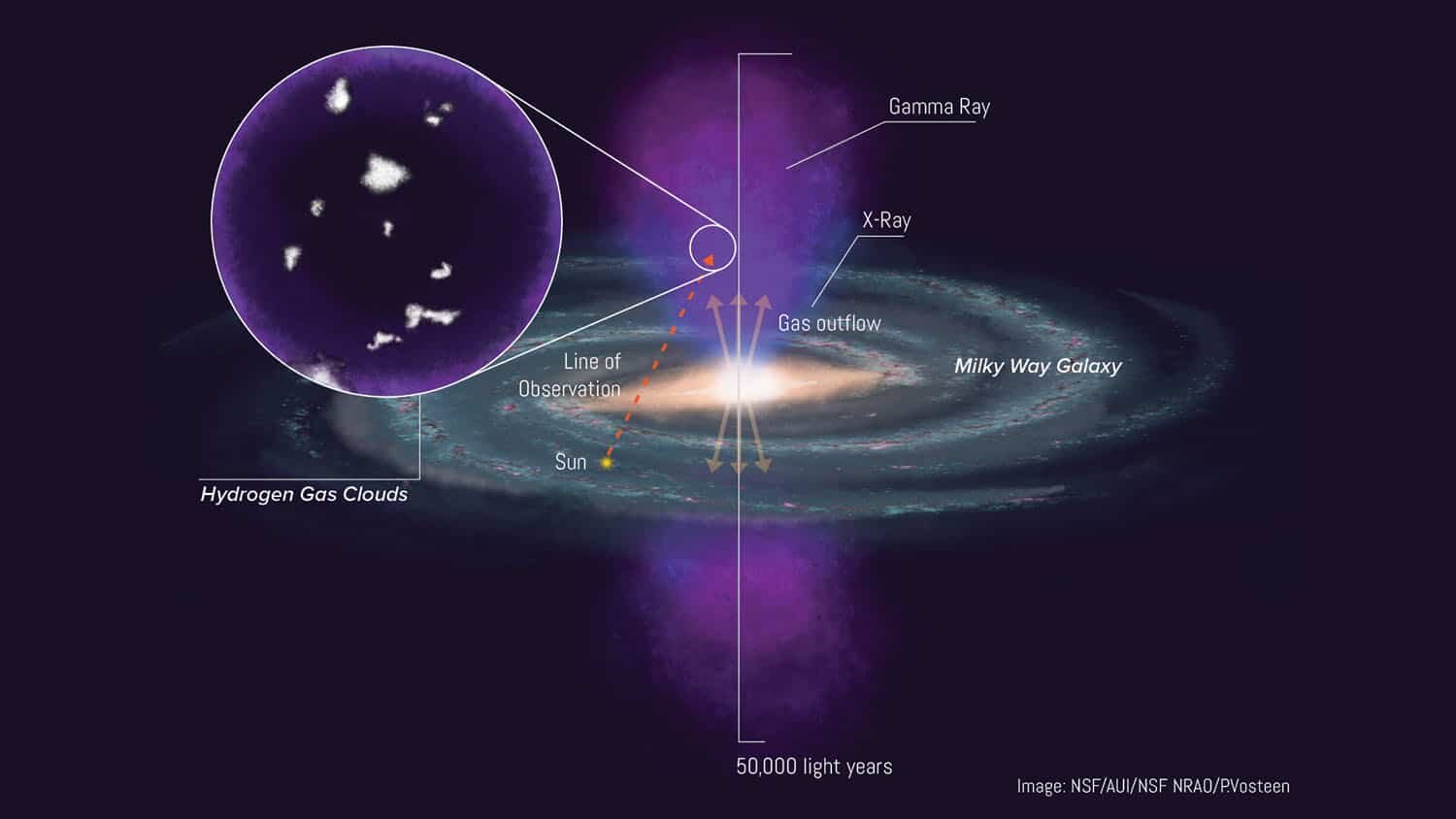

The identification of the 1408 nova joins a growing list of historical Chinese guest stars that have been matched with known astronomical events. Perhaps the most famous is the supernova of 1054, observed so clearly in Chinese records that it led modern astronomers to the Crab Nebula—a glowing supernova remnant still expanding today.

These identifications offer powerful reminders that the sky is a living archive. With every nova we match to a guest star, we extend the temporal resolution of astrophysics and build a deeper understanding of the stars’ long-term evolution. The universe, it turns out, keeps meticulous records of its own—as long as someone is watching, and someone else is listening hundreds of years later.

The rediscovery of the 1408 nova proves that sometimes, the light from long-dead stars reaches us not just through telescopes, but through ink and parchment, patience and scholarship. In that sense, Hu Guang and his fellow court astronomers were not just chroniclers of the sky. They were the earliest astrophysicists, offering us, across centuries, a glimpse of a cosmos in motion.

Reference: Boshun Yang et al, Was there a (super)nova in 1408? arXiv (2025). DOI: 10.48550/arxiv.2505.10728