China’s story is one of the longest and most enduring in human history. To speak of Ancient China is to speak of a civilization that has endured for millennia, shaping not only its own destiny but also influencing cultures far beyond its borders. Like the mighty Yellow River—both nurturing and destructive—the flow of dynasties across time carved the heart of a nation. Each dynasty, with its triumphs and tragedies, innovations and collapses, became a layer in the living bedrock of Chinese civilization.

When we look back at the dynasties of Ancient China, we are not merely recounting dates and rulers; we are tracing the growth of an identity. These dynasties did not exist in isolation—they were stages in a continuous play of power, philosophy, art, and survival. From myth-shrouded beginnings to the glory of imperial courts, the dynastic story of China is a tale of resilience, reinvention, and unbroken cultural memory.

The Legendary Beginnings: Xia Dynasty

The roots of Chinese civilization reach deep into legend. The Xia Dynasty, said to have existed around 2070–1600 BCE, is often regarded as the first dynasty in Chinese history, though its existence blends myth with archaeology. Ancient texts such as The Records of the Grand Historian by Sima Qian recount the story of Yu the Great, a cultural hero who tamed the devastating floods of the Yellow River and established a hereditary line of rulers.

For centuries, the Xia was doubted as a historical reality, dismissed as a fabrication of later dynasties seeking legitimacy. But archaeological findings at sites like Erlitou in Henan Province suggest a flourishing Bronze Age culture that could correspond to the Xia. Whether myth or reality, the Xia dynasty holds an essential place as the symbolic beginning of Chinese civilization, representing humanity’s triumph over chaos through ingenuity, leadership, and community.

The Shang Dynasty: The Dawn of Recorded History

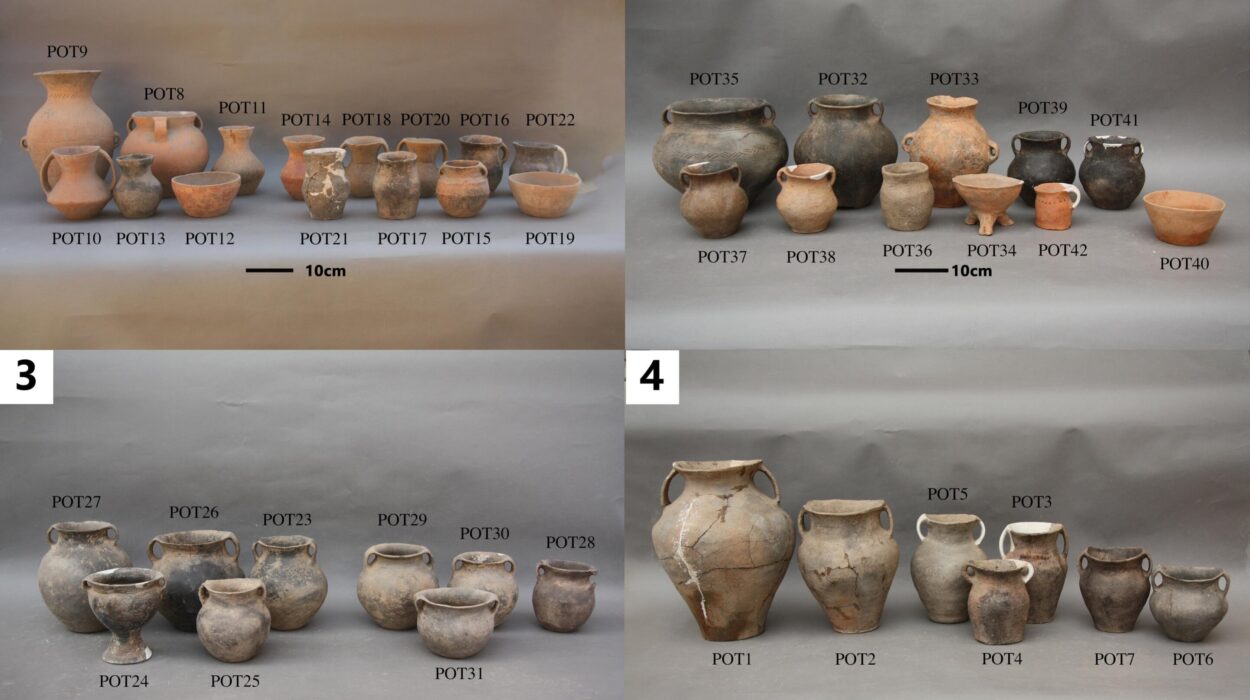

Around 1600 BCE, the Shang Dynasty emerged, leaving behind the first clear evidence of Chinese writing, culture, and statecraft. Known for their mastery of bronze casting, the Shang created ritual vessels of exquisite design, objects that were as much spiritual as they were artistic. These vessels connected the living with the ancestral spirits, reflecting a society deeply rooted in reverence for lineage and the supernatural.

Oracle bones—inscribed turtle shells and ox scapulae—are the most striking legacy of the Shang. They record divinations, battles, weather patterns, and royal decrees, forming the earliest written Chinese records. Through them, we glimpse the lives of kings, priests, and warriors, and the complex ritual system that bound heaven, earth, and human rulers into one cosmic order.

The Shang capital, Anyang, reveals a society of hierarchy and sophistication: palaces, workshops, and tombs where rulers were buried with treasures, servants, and even sacrificed captives. Though their reign ended in violence, the Shang left a written language, technological mastery, and a cultural foundation that endured across dynasties.

The Zhou Dynasty: The Mandate of Heaven

The fall of the Shang around 1046 BCE gave rise to the Zhou Dynasty, which lasted longer than any other—spanning nearly 800 years. The Zhou introduced one of the most powerful ideas in Chinese history: the Mandate of Heaven. Unlike the divine right of kings in Europe, the Mandate of Heaven was conditional. Heaven granted rulers the right to govern, but if they became corrupt or tyrannical, heaven would withdraw its favor, justifying rebellion. This concept legitimized dynastic change for centuries to come.

The Zhou period was marked by profound cultural and intellectual growth. Early Western Zhou rulers maintained feudal structures, distributing land to loyal nobles who owed military service. Over time, however, power fragmented, ushering in the Eastern Zhou era, divided into the Spring and Autumn Period and the Warring States Period.

This era of division was paradoxically one of China’s most fertile intellectually. It was the time of the “Hundred Schools of Thought,” when Confucius taught morality and order, Laozi articulated the path of Daoism, and Legalists emphasized strict laws and governance. The Zhou may have lost political unity, but they created a philosophical foundation that still guides China today.

The Qin Dynasty: The First Empire

Out of the chaos of the Warring States arose the Qin, under the formidable leadership of Qin Shi Huang. In 221 BCE, he proclaimed himself the First Emperor of China, uniting the fractured states into one empire for the first time. Though the Qin Dynasty lasted only 15 years, its impact was monumental.

Qin Shi Huang centralized power, abolished feudal fiefdoms, standardized weights, measures, currency, and even the written script. These reforms bound the empire together, fostering unity across vast territories. His ambition extended to monumental projects: the first version of the Great Wall to ward off northern nomads, and the construction of roads and canals that connected his empire.

But Qin rule was also infamous for its harshness. Guided by Legalist philosophy, the emperor imposed strict laws and brutal punishments. Dissent was crushed—famously through the burning of books and the execution of scholars. His tomb, guarded by the awe-inspiring Terracotta Army, symbolizes both his power and his obsession with immortality.

Though short-lived, the Qin Dynasty laid the blueprint for imperial China, proving that a vast, centralized empire could exist and endure.

The Han Dynasty: The Golden Age

Following the fall of the Qin, the Han Dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE) rose to power, ushering in one of the most celebrated golden ages of Chinese civilization. Under the Han, China expanded its borders, stabilized governance, and nurtured arts and sciences that flourished for centuries.

The Han adopted Confucianism as the ideological backbone of the state, blending it with Legalist practicality. The creation of the imperial examination system allowed talented men, not just nobles, to enter government service, laying the foundation for a meritocratic bureaucracy.

It was during the Han era that the Silk Road opened, linking China to Central Asia, the Middle East, and Rome. Silk, paper, porcelain, and ideas traveled along this route, making China a hub of global exchange long before globalization was conceived.

Technological and scientific advancements thrived. Paper was invented, revolutionizing record-keeping and literature. Astronomers mapped the skies, doctors refined herbal medicine, and artisans perfected ceramics and metallurgy.

The Han Dynasty also shaped China’s cultural identity. To this day, the Chinese people call themselves the Han, a testament to the dynasty’s lasting influence. Yet, like all dynasties, it too faced decline—corruption, natural disasters, peasant uprisings, and invasions weakened the empire, leading to its fall in 220 CE.

The Era of Division: Three Kingdoms to Sui

The collapse of the Han plunged China into centuries of disunity, known as the Period of Disunion (220–589 CE). Warlords carved the land into rival states, most famously the Three Kingdoms: Wei, Shu, and Wu. This era inspired legendary tales of loyalty, betrayal, and strategy, immortalized in the epic Romance of the Three Kingdoms.

Despite political chaos, Chinese culture adapted and grew. Buddhism spread from India, offering solace in uncertain times and reshaping Chinese spirituality. Northern and southern dynasties flourished artistically, producing poetry, painting, and Buddhist sculpture of remarkable beauty.

Eventually, reunification came under the Sui Dynasty (581–618 CE). Though brief, the Sui built the Grand Canal, linking north and south, and restored centralized governance, setting the stage for the Tang—a dynasty often hailed as China’s greatest.

The Tang Dynasty: The Flourishing Empire

The Tang Dynasty (618–907 CE) stands as a pinnacle of Chinese civilization, a time of unmatched prosperity, openness, and cultural brilliance. With Chang’an (modern Xi’an) as its capital, Tang China became one of the largest and most cosmopolitan cities in the world. Merchants, scholars, and travelers from distant lands converged there, making it a hub of global exchange.

Under Tang rule, China expanded its borders, asserting influence across East and Central Asia. The dynasty perfected the civil service system, ensuring that officials were selected through rigorous examinations rooted in Confucian classics.

Culturally, the Tang was a golden age of poetry, with masters like Li Bai and Du Fu crafting verses that continue to resonate. Painters captured landscapes with philosophical depth, while Buddhist art reached new heights in cave temples such as Dunhuang.

Women in Tang society enjoyed greater freedom than in many other dynasties, epitomized by Empress Wu Zetian, the only woman to rule China in her own name. Yet, even this golden age eventually succumbed to internal rebellion, corruption, and nomadic pressures, leading to its decline.

The Song Dynasty: Innovation and Refinement

Emerging after the Tang, the Song Dynasty (960–1279 CE) presided over another era of remarkable advancement, though one often overshadowed by foreign invasions. Despite military challenges, the Song excelled in innovation, economy, and culture.

Song China witnessed the world’s first use of paper money, advanced banking systems, and a thriving urban culture. Agricultural innovations, such as fast-ripening rice from Champa (Vietnam), fueled population growth and prosperity.

Scientifically, the Song led the world in discoveries: movable-type printing revolutionized knowledge; gunpowder changed warfare forever; and the magnetic compass enabled navigation across oceans. Song painters and calligraphers elevated the arts, capturing nature’s subtle beauty with philosophical sophistication.

Yet military weakness plagued the dynasty. Northern invasions by the Jurchen and eventually the Mongols forced the Song southward, where the Southern Song held on until Kublai Khan’s conquest in 1279, marking the dawn of Mongol rule.

The Yuan Dynasty: Mongol Rule in China

The Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368 CE), established by Kublai Khan, marked the first time China was ruled entirely by a foreign power. The Mongols, though conquerors, adopted Chinese systems of governance while also opening China further to global connections.

Kublai Khan’s court welcomed visitors like Marco Polo, who described the wealth and marvels of the empire to Europe. The Yuan facilitated trade along the Silk Road, integrating China into a vast Eurasian network.

Yet Mongol rule was also harsh, with ethnic divisions privileging Mongols and foreign allies over the Han Chinese majority. Heavy taxation and corruption led to widespread resentment. Rebellions eventually rose, paving the way for the native Ming Dynasty.

The Ming Dynasty: Restoration and Greatness

The Ming Dynasty (1368–1644 CE) restored Han Chinese rule, emphasizing stability, tradition, and grandeur. Its rulers rebuilt infrastructure, strengthened the Great Wall, and promoted Confucian governance. The Forbidden City in Beijing, constructed during this era, symbolized imperial authority and architectural brilliance.

The Ming also looked outward. Admiral Zheng He led vast naval expeditions in the early 15th century, reaching as far as Africa with treasure fleets that dwarfed European ships. These voyages demonstrated China’s maritime power but were later abandoned in favor of inward-looking policies.

Ming artisans perfected porcelain, silk, and literature, creating cultural treasures still admired worldwide. Yet, by the 17th century, corruption, economic strain, and external threats weakened the dynasty, leading to its fall to the Manchu-led Qing Dynasty.

The Dynastic Legacy

From the legendary Xia to the mighty Ming, the dynasties of Ancient China shaped a civilization unparalleled in endurance and influence. Each dynasty contributed to the grand tapestry—philosophy, governance, art, science, and the ever-evolving idea of what it meant to be Chinese.

What makes China’s dynastic history so remarkable is not merely its longevity but its adaptability. Dynasties rose and fell, but Chinese civilization persisted, absorbing foreign influences, reinventing traditions, and maintaining continuity across thousands of years.

Conclusion: The Eternal Mandate

The dynasties of Ancient China were more than political regimes; they were embodiments of a cosmic rhythm—the rise, flourishing, and decline that mirrored the cycles of nature. Each dynasty carried the Mandate of Heaven, and when it faltered, another rose to take its place.

Today, when we reflect on Ancient China, we see not just a sequence of rulers, but the birth of ideas that continue to shape the modern world: the importance of harmony, the value of learning, the balance of authority and morality, and the resilience of culture.

The dynasties that shaped China did more than build walls, palaces, or armies. They built a civilization that has endured for over four thousand years, a civilization that, like the rivers that nourish it, continues to flow—eternal, resilient, and profoundly human.