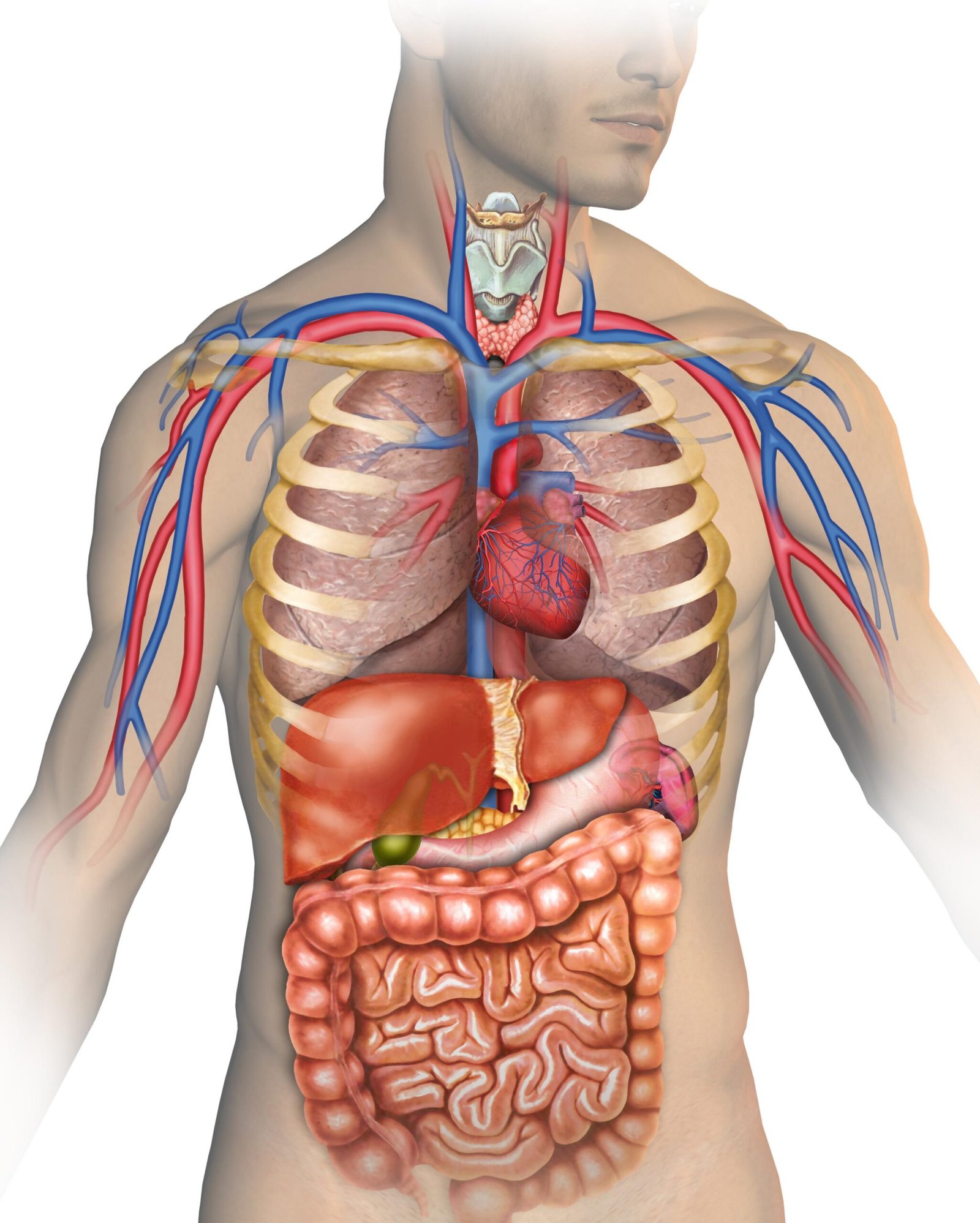

The human body feels complete, intentional, almost perfectly designed. Every bone, nerve, and organ seems essential, working together in a delicate balance that keeps us alive. And yet, hidden within us are reminders of a very different past. Evolution does not erase things cleanly. It modifies, repurposes, and sometimes leaves behind structures that once mattered deeply but now linger like architectural relics in an ancient city.

These parts are not mistakes. They are evolutionary echoes—biological fossils embedded in flesh. Some still perform minor roles, others are mostly silent, and a few can even cause trouble. They tell the story of where we came from, what we used to be, and how survival reshaped us over millions of years.

Here are seven parts of the human body we no longer truly need, and the remarkable evolutionary stories behind them.

1. The Appendix

The appendix has become the most famous “useless” organ in the human body, largely because of how dramatically it can betray us. This small, finger-like pouch extends from the large intestine and for generations was dismissed as a pointless leftover from evolution. If it becomes inflamed, it can rupture, causing life-threatening infection. Millions of people live perfectly healthy lives after having it removed. That alone raises a powerful question: why do we have it at all?

To understand the appendix, we have to travel back to a time when human ancestors relied heavily on plant-based diets rich in tough, fibrous material. In many herbivorous mammals, a large appendix or cecum helps break down cellulose using specialized bacteria. As human diets changed and cooking softened food, this digestive function became less necessary. The appendix shrank dramatically, losing its primary role.

Modern research suggests the appendix may still serve as a reservoir for beneficial gut bacteria, helping repopulate the intestines after severe illness. But this role is not essential. People without an appendix do just fine, and many species thrive without one entirely. The appendix is not useless in the strictest sense, but it is no longer necessary for survival. It is a quiet remnant of a digestive system we no longer use.

Emotionally, the appendix reminds us that evolution favors “good enough,” not perfection. Nature does not redesign from scratch; it adapts what already exists, even if it becomes fragile or risky over time.

2. Wisdom Teeth

Wisdom teeth are a modern rite of passage, often associated with pain, swelling, and surgical removal. These third molars usually emerge in late adolescence or early adulthood, long after the jaw has finished growing. For many people, there simply isn’t enough room for them, causing crowding, infection, or impaction.

But wisdom teeth once had a purpose. Early humans had larger jaws and ate coarse, unprocessed foods that wore down teeth quickly. Extra molars were valuable backup tools for grinding roots, raw meat, and tough plants. Losing teeth was common, and replacements mattered.

As cooking, tool use, and food processing became widespread, jaws grew smaller and diets became softer. Teeth experienced less wear, and extra molars were no longer necessary. Evolution has not yet caught up fully, so wisdom teeth still form in many people, even though they often create more problems than benefits.

Some people are now born without wisdom teeth at all, a sign that evolution may be phasing them out. Their gradual disappearance is happening not because we consciously decided they were unnecessary, but because bodies that didn’t form them had fewer complications.

Wisdom teeth are a reminder that our biology still reflects ancient survival needs, even when modern life has made them obsolete.

3. The Coccyx (Tailbone)

At the base of your spine sits the coccyx, commonly known as the tailbone. It is small, curved, and often painful when injured. Its name alone hints at its origin: it is the remnant of a tail.

Our distant ancestors had tails that helped with balance, communication, and movement through trees. As humans evolved upright posture and bipedal walking, tails lost their usefulness. Over time, they shrank, fused, and became the coccyx.

Today, the coccyx does serve as an attachment point for muscles and ligaments that support pelvic organs. However, these muscles could function without it, and injuries to the coccyx can cause chronic pain without providing any survival advantage. People born without a coccyx can live entirely normal lives.

Occasionally, humans are even born with vestigial tails, a striking developmental reminder of our evolutionary past. These rare cases underscore that the genetic blueprint for tails still exists, quietly embedded in our DNA.

The coccyx is a silent storyteller. It whispers that humans were once something very different, shaped by gravity, trees, and movement in ways our modern bodies no longer require.

4. Body Hair (in Its Original Form)

Humans are mammals, and mammals are supposed to be furry. Yet compared to our relatives, humans are strangely naked. We still grow hair, but not in the dense, insulating coat that once covered our ancestors.

Early humans were likely covered in thick body hair that protected against cold, sun, and insects. As our ancestors began to walk upright and travel long distances in hot climates, heavy fur became a disadvantage. Sweating became a more efficient cooling system, and bare skin allowed heat to escape more easily.

Over time, thick body hair was lost, leaving behind fine, short hairs known as vellus hair. These hairs still exist across most of the body, but they no longer serve their original purpose. They offer minimal insulation and protection.

Some body hair remains functional, such as scalp hair, which protects against sun exposure, and eyebrows and eyelashes, which help keep debris out of the eyes. But the widespread body hair humans once needed for survival is no longer necessary in modern environments.

The persistence of fine body hair is an evolutionary compromise. It costs little energy to maintain, so there has been no strong pressure to eliminate it entirely. Like many vestigial traits, it remains simply because it does not interfere enough to be removed.

5. The Plica Semilunaris (Third Eyelid Remnant)

In the inner corner of each human eye is a small fold of tissue called the plica semilunaris. Most people never notice it, yet it is the vestige of a third eyelid, known as the nictitating membrane.

In many animals, this membrane sweeps across the eye horizontally, providing protection and moisture while maintaining vision. Birds, reptiles, and some mammals rely on it for survival, especially in harsh environments.

Humans no longer need this structure. Our eyes evolved differently, relying on blinking and tear production instead. The plica semilunaris no longer moves or serves a protective role. It remains as a faint anatomical trace of a function that once mattered deeply.

This tiny fold of tissue is one of the clearest examples of a body part that serves no meaningful purpose today. It does not harm us, but it does not help us either. It is a biological footnote, a quiet annotation left behind by evolution.

6. The Palmaris Longus Muscle

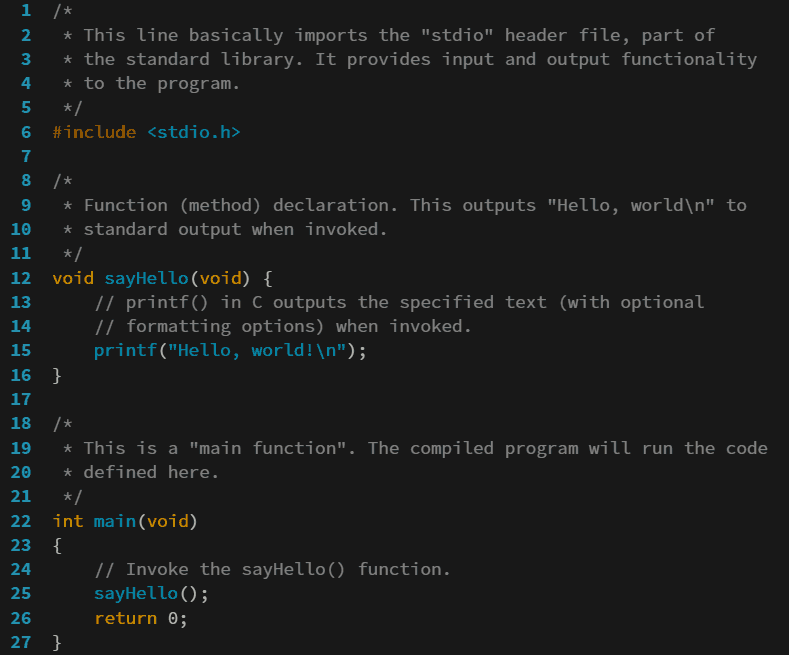

The palmaris longus is a slender muscle in the forearm that helps with wrist flexion and grip strength. Here’s the fascinating part: about 10–15 percent of people don’t have it at all, and most never notice.

You can test for it by touching your thumb to your pinky and flexing your wrist. If a tendon pops up in the middle of your wrist, you have it. If not, you’re missing it—and your life is almost certainly unaffected.

This muscle was once more important for climbing and grasping, especially in arboreal ancestors who relied on strong, sustained grips. As humans transitioned to tool use and different movement patterns, this muscle became less critical.

Surgeons often remove the palmaris longus tendon for reconstructive procedures because its absence causes no functional loss. That alone confirms its redundancy.

The palmaris longus is a striking example of evolution in progress. Some people still have it, some don’t, and the difference rarely matters. It is a body part quietly fading out, generation by generation.

7. Male Nipples

Male nipples often provoke jokes, but their existence is rooted in early human development. All human embryos follow the same basic blueprint during the earliest stages of growth. Nipples form before sex differentiation occurs. By the time hormones shape male or female anatomy, nipples are already there.

In females, nipples play a critical role in lactation and infant survival. In males, they serve no biological function. They cannot produce milk under normal circumstances, and their removal would not affect health or reproduction.

Male nipples persist because there is no evolutionary pressure strong enough to eliminate them. They do not cause harm, and removing them would require a complete redesign of early embryonic development, which evolution rarely does unless necessary.

Their presence is not evidence of poor design, but of efficiency. Evolution modifies what exists rather than rebuilding from scratch. Male nipples remain because they are harmless passengers on the developmental journey.

They are a reminder that biology is not guided by intent or aesthetics, but by practicality and survival.

What These Vestigial Parts Teach Us About Being Human

These seven body parts are more than curiosities. They are living records of evolutionary history written into flesh and bone. They show us that the human body is not a finished product but a snapshot in an ongoing process.

Evolution does not care about comfort, beauty, or logic. It cares about survival and reproduction. If something does not significantly interfere with those goals, it can remain—even if it is no longer useful.

These remnants also challenge the idea of perfection. The human body is extraordinary, but it is not flawless. It carries inefficiencies, vulnerabilities, and contradictions. And yet, those imperfections tell a deeper story: one of adaptation, resilience, and continuity.

When we look at these unnecessary parts, we are not seeing mistakes. We are seeing evidence of our connection to every organism that came before us. We are seeing the long, winding path that led to modern humanity.

In that sense, these vestigial structures are not useless at all. They remind us that we are not separate from nature, but shaped by it. They show that our bodies are archives, carrying memories of ancient lives, forgotten environments, and survival strategies that once mattered.

To understand them is to understand ourselves—not as static beings, but as evolving stories still being written.