Few ideas in everyday life are as widely accepted, casually invoked, and confidently defended as the “5-second rule.” Drop a piece of food on the floor, scoop it up quickly, and reassure yourself that it is still safe to eat because it did not remain in contact with the ground for long enough to become contaminated. This rule is repeated in kitchens, dorm rooms, playgrounds, and restaurants across the world. It feels intuitive, comforting, and practical. It also feels harmless, a small act of rationalization in an imperfect world.

Yet when examined through the lens of microbiology, physics, and food science, the 5-second rule collapses almost entirely. It is not merely a harmless exaggeration or a slight oversimplification. It is a misconception that fundamentally misunderstands how microbes behave, how contamination occurs, and how quickly invisible processes can unfold. The truth is less reassuring, but far more fascinating. Food does not need seconds to become contaminated. In many cases, it does not even need a moment.

Understanding why the 5-second rule is a lie requires letting go of human-scale intuition and entering the microscopic world, where time, contact, and cleanliness operate by very different rules. The following five reasons explain, in scientifically grounded detail, why the 5-second rule fails—and why believing it says more about human psychology than about food safety.

1. Bacteria Transfer Happens Almost Instantly

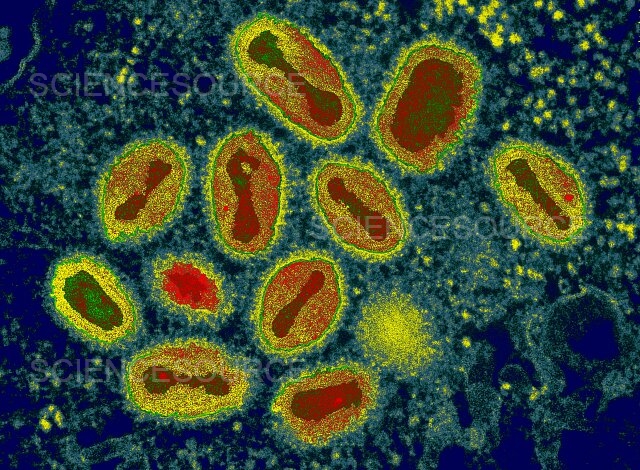

The central assumption behind the 5-second rule is that bacteria require time to move from a surface onto food. The image is often imagined like insects slowly crawling upward, as if contamination were a gradual process that can be interrupted by quick action. In reality, bacterial transfer is not a slow migration. It is a near-instantaneous physical interaction.

When food touches a surface, bacteria are transferred through direct contact. This process is governed by basic physics and surface chemistry, not by biological decision-making. Bacteria do not need time to “climb” onto food; they are already present on the surface, and contact alone is enough to move them. The moment food makes contact with a contaminated surface, bacteria can adhere to it.

Laboratory studies examining bacterial transfer have consistently shown that measurable contamination can occur in less than one second. The transfer does not increase smoothly over time from zero to danger. Instead, it often occurs immediately, with longer contact time only slightly increasing the number of bacteria transferred. In other words, the difference between one second and five seconds is often negligible compared to the difference between zero contact and any contact at all.

This is particularly true for moist or soft foods. Moisture acts as a bridge, allowing bacteria to move more easily between surfaces. A slice of watermelon, a piece of bread, or a cooked noodle provides an ideal environment for bacterial transfer because water allows adhesion forces to act efficiently. Dry foods may transfer fewer bacteria, but fewer does not mean none.

The emotional discomfort of this fact lies in how it contradicts common sense. Humans experience time in seconds and minutes, so we assume that biological processes must follow similar scales. In the microbial world, however, physical contact is what matters, not duration. From a bacterium’s perspective, the moment food hits the floor is already an eternity.

2. Floors Are Far Dirtier Than They Appear

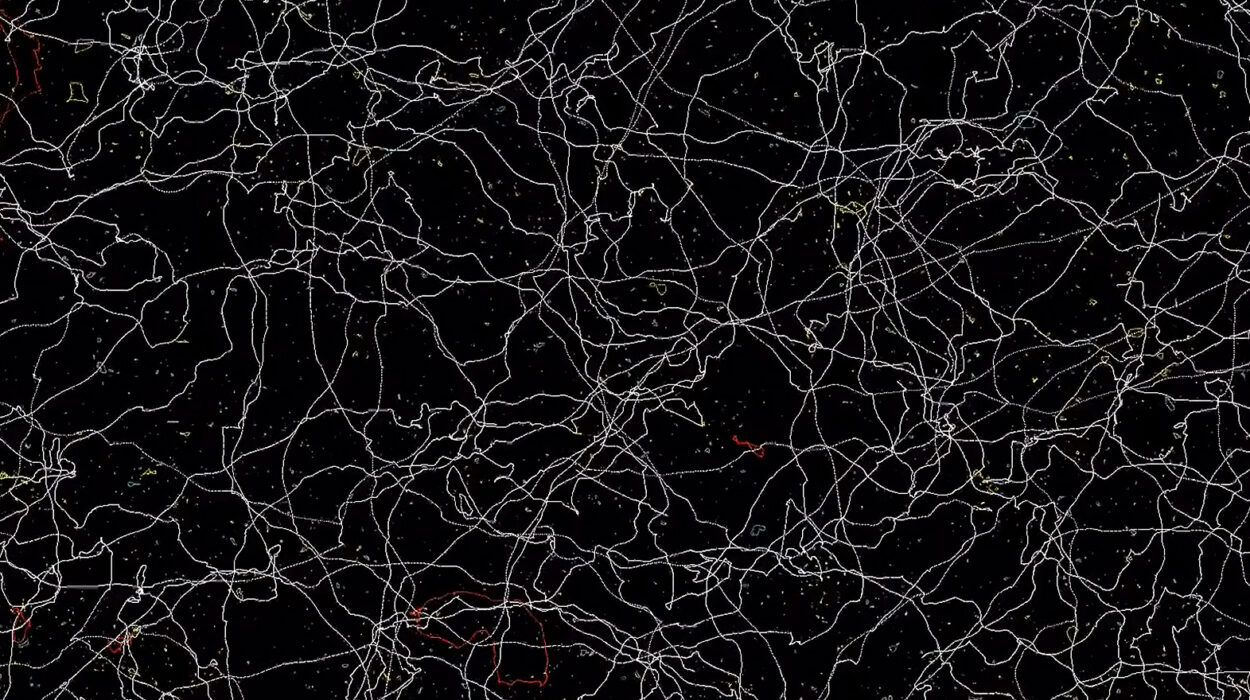

Another comforting belief supporting the 5-second rule is the idea that floors are not really that dirty, especially in familiar environments such as one’s own home. The logic goes something like this: if the floor looks clean, smells clean, and is cleaned occasionally, then it must be relatively safe. This belief confuses visual cleanliness with microbiological safety.

Floors are among the most microbially diverse surfaces in indoor environments. They accumulate bacteria from shoes, pets, air currents, food particles, and human movement. Every step brings microorganisms from outside, including soil bacteria, fecal microbes, and environmental pathogens. Even barefoot walking redistributes skin bacteria across the floor.

Importantly, many dangerous microorganisms are invisible and odorless. A surface does not need to look dirty to be heavily contaminated. Pathogenic bacteria such as Salmonella, Escherichia coli, and Staphylococcus aureus cannot be detected by sight or smell. A kitchen floor that appears spotless may still harbor millions of bacterial cells per square centimeter.

The problem is compounded by the way floors are cleaned. Typical household cleaning removes visible dirt but often does not eliminate all bacteria. Even disinfectants reduce microbial populations rather than sterilizing surfaces completely. Within hours of cleaning, bacteria begin to recolonize surfaces through air movement and contact.

Public spaces are even more concerning. Cafeterias, classrooms, hospitals, and public transport areas accumulate microbes from countless individuals. Dropping food in such environments exposes it to a microbial community shaped by thousands of human interactions, not just one household’s habits.

The emotional pull of the 5-second rule depends on trust—trust in our environment, our routines, and our sense of control. Science reveals that this trust is often misplaced. Floors are not neutral surfaces waiting to contaminate food slowly. They are already alive with microscopic activity.

3. Not All Bacteria Are Harmless, and You Cannot Tell Which Are Present

A common defense of the 5-second rule is the argument that “a little dirt is good for you” or that exposure to bacteria helps strengthen the immune system. While it is true that not all bacteria are harmful and that the human body coexists with trillions of beneficial microbes, this reasoning fails when applied indiscriminately to food safety.

The problem is not that all bacteria are dangerous, but that there is no reliable way to know which bacteria are present on a given surface. Pathogenic bacteria do not announce themselves. They look exactly like harmless microbes under everyday conditions. The immune system may handle small exposures, but it is not invincible, and repeated or high-dose exposures increase the risk of illness.

Foodborne pathogens are particularly concerning because they are adapted to survive ingestion. Some produce toxins that cause illness even if the bacteria themselves are killed. Others require only a small number of cells to initiate infection. Vulnerable populations, including children, the elderly, and individuals with compromised immune systems, face even greater risks.

Moreover, bacteria are not evenly distributed across surfaces. Microbial “hot spots” can form where moisture, food residue, or organic matter accumulate. A dropped piece of food may land directly on such a spot, receiving a concentrated dose of microbes regardless of how quickly it is picked up.

The emotional danger of the 5-second rule lies in false reassurance. It encourages people to ignore uncertainty and replace it with a simple narrative: quick equals safe. In reality, safety depends on variables that cannot be assessed in the moment. The absence of immediate illness does not mean the absence of risk; it often means only that the body was lucky.

4. Food Texture and Moisture Matter More Than Time

If time is not the decisive factor in contamination, what is? Research consistently points to the physical properties of food itself. Texture, moisture content, and surface area play a far greater role in bacterial transfer than how long the food remains on the ground.

Moist foods act like microbial magnets. Water facilitates the movement and adhesion of bacteria, allowing them to transfer efficiently from one surface to another. A wet apple slice, a piece of cooked meat, or a slice of cheese provides an ideal environment for bacteria to attach and remain viable. In such cases, contamination can be substantial almost immediately.

Porous foods also increase risk. Bread, cake, and other spongy items have microscopic crevices that trap bacteria, making them difficult to remove even if the surface appears clean. Once bacteria enter these spaces, they are shielded from drying and mechanical removal.

By contrast, very dry foods such as crackers or nuts may transfer fewer bacteria, but this does not mean they are safe. Even low levels of contamination can be problematic depending on the type of bacteria involved. Additionally, dry foods can still pick up pathogens if the surface they contact is heavily contaminated.

This variability exposes the weakness of the 5-second rule as a universal guideline. It treats all foods and surfaces as equal, ignoring the complex interactions between material properties and microbial behavior. Science does not support one-size-fits-all rules; it reveals a landscape of conditional risks.

Emotionally, this complexity is uncomfortable. Humans prefer simple rules that reduce decision-making effort. The 5-second rule provides exactly that, at the cost of accuracy. Reality, however, demands nuance, and food safety is no exception.

5. The Rule Persists Because of Psychology, Not Science

Perhaps the most revealing reason the 5-second rule is a lie is that its persistence has little to do with evidence and everything to do with human psychology. The rule survives because it fulfills emotional and cognitive needs, not because it reflects how contamination works.

One powerful factor is loss aversion. Humans dislike wasting food, especially food they value or anticipate enjoying. The 5-second rule offers a convenient justification to avoid throwing something away. By framing the decision as scientifically acceptable, it reduces guilt and regret.

Another factor is familiarity bias. People are more likely to trust environments they know well, such as their own homes. This trust extends to surfaces, even when there is no objective basis for it. The rule becomes a ritual of reassurance, reinforcing the belief that familiar spaces are safer than they truly are.

Social reinforcement also plays a role. The 5-second rule is often shared humorously, passed down through families, and treated as common knowledge. Challenging it can feel pedantic or overly cautious, especially in social settings where eating dropped food is normalized.

Finally, there is the illusion of control. Picking up food quickly creates a sense of action and agency, as if speed itself can undo contamination. This feeling is emotionally satisfying, even though it has little impact on microbial reality.

Science does not spread as easily as myths that align with human instincts. The 5-second rule persists not because it works, but because it feels right. It allows people to navigate a messy world with a sense of order, even if that order is imaginary.

Conclusion: Why Letting Go of the 5-Second Rule Matters

The 5-second rule is not just a harmless superstition; it is a misunderstanding of how the microscopic world operates. Bacteria do not wait politely for time to pass. They transfer instantly, invisibly, and unpredictably. Floors are not passive surfaces, and food is not protected by speed alone. What determines safety is a complex interplay of surface contamination, food properties, and microbial identity—factors that cannot be judged in the moment.

Letting go of the 5-second rule does not mean living in fear or obsessing over cleanliness. It means replacing comforting myths with informed awareness. Food safety is not about perfection, but about understanding risk and making decisions based on evidence rather than intuition.

There is something deeply human about wanting simple rules in a complex world. The challenge is learning when those rules serve us and when they mislead us. The story of the 5-second rule reminds us that science often asks us to trade emotional comfort for clarity—and that clarity, though sometimes unsettling, ultimately helps us live more wisely.