Earth’s crust is a dynamic archive of deep time, shaped by heat, pressure, chemistry, and chance. Most minerals occur in many places because the physical and chemical conditions required to form them recur throughout geological history. Quartz, feldspar, calcite, and hundreds of others appear again and again across continents and oceans. Yet a very small number of minerals defy this pattern. They exist only where an extraordinarily specific sequence of conditions unfolded once—and never quite repeated itself elsewhere.

These minerals are not merely rare in the sense of being scarce. They are geographically unique. According to current mineralogical records and accepted scientific descriptions, each of the following minerals has been confirmed from only a single locality on Earth. Their existence reflects extreme geological precision: a narrow temperature window, an unusual chemical mix, a fleeting moment in planetary history. Together, they reveal how finely tuned Earth’s processes can be, and how easily a mineral can slip into existence only once.

What follows is not just a catalog of rarity, but a story of how Earth expresses its creativity through matter—quietly, invisibly, and sometimes only in one place.

1. Painite – Mogok Valley, Myanmar

Painite stands as one of the most famous examples of a mineral once thought nearly mythical. For decades after its discovery in the 1950s, painite was known only from a handful of crystals found in the Mogok Valley of northern Myanmar. For a long period, it held the title of the rarest mineral on Earth, with fewer than a dozen known specimens.

Scientifically, painite is remarkable because of its chemistry. It is a borate mineral containing calcium, zirconium, aluminum, and boron—an unusual combination that requires an exceptionally specific geochemical environment. Boron-rich fluids, zirconium-bearing rocks, and precise temperature and pressure conditions must converge at exactly the right moment. Such convergence appears to have occurred only within a small geological pocket of the Mogok metamorphic belt.

The Mogok Valley itself is an extraordinary geological setting, known for producing rubies, sapphires, and spinels of exceptional quality. Painite formed during high-grade metamorphism, when existing rocks were chemically reworked deep within Earth’s crust. Its reddish-brown to deep orange crystals carry the memory of those intense conditions.

Although later discoveries expanded the number of known painite crystals, all verified specimens still originate from the same geological region. Painite’s uniqueness is therefore not just about rarity, but about a singular geological story written into one valley on Earth.

2. Benitoite – San Benito County, California, USA

Benitoite is a striking blue barium titanium silicate whose beauty rivals that of sapphire. Yet unlike sapphire, benitoite’s natural occurrence is astonishingly limited. It has been confirmed in gem-quality form only from a single locality in San Benito County, California.

This mineral formed within an unusual geological environment involving serpentinite rocks altered by hydrothermal fluids rich in barium and titanium. Such chemical conditions are exceedingly rare, especially when combined with the precise crystallization environment required for benitoite’s distinctive trigonal structure.

Benitoite fluoresces bright blue under ultraviolet light, a property that has fascinated mineralogists and gem collectors alike. Its optical behavior is directly linked to its crystal lattice and trace-element composition, both of which reflect the highly specific chemistry of its birthplace.

The San Benito locality represents a geochemical anomaly—a brief intersection of elemental availability and physical conditions that has not been duplicated elsewhere. Despite extensive exploration, no other confirmed natural source has produced benitoite in comparable form, making it a mineral whose existence is inseparable from a single hillside in California.

3. Hibonite-(Fe) – Mount Carmel, Israel

Hibonite is a calcium aluminum oxide mineral originally discovered in meteorites, but a specific iron-rich variety known as hibonite-(Fe) has been identified only from one place on Earth: Mount Carmel in northern Israel.

This mineral formed under extremely high-temperature, low-oxygen conditions, resembling those found in the early solar system rather than typical terrestrial environments. Its presence at Mount Carmel is linked to a unique geological setting involving mantle-derived materials brought close to the surface through volcanic processes.

The chemistry of hibonite-(Fe) requires oxygen-poor conditions that are almost never sustained in Earth’s crust. The Mount Carmel region appears to have briefly recreated these rare conditions, allowing the mineral to crystallize before being preserved within volcanic rocks.

What makes hibonite-(Fe) emotionally compelling is its dual identity. It bridges Earth and space, sharing mineralogical ancestry with cosmic materials while remaining tied to a single mountain on our planet. Its existence reminds us that Earth can, under rare circumstances, echo the conditions of its own formation.

4. Davemaoite – Deep Mantle Beneath Earth’s Surface

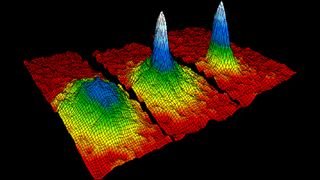

Davemaoite is one of the most extraordinary mineral discoveries of the modern era, not because of its beauty, but because of where it exists. This calcium silicate perovskite mineral forms only under the immense pressures of Earth’s lower mantle, hundreds of kilometers below the surface.

For decades, its existence was predicted by physics and mineral chemistry, but direct evidence remained elusive. Davemaoite was finally identified within tiny inclusions trapped inside a diamond that originated deep within the mantle. To date, this remains the only confirmed natural occurrence of the mineral.

The pressures required to stabilize davemaoite exceed those found anywhere on Earth’s surface. Its crystal structure collapses at lower pressures, meaning it cannot survive normal geological environments. Only the diamond that encased it preserved its structure during ascent.

Davemaoite is unique not because it is scarce in the mantle—models suggest it may be abundant there—but because it has been observed only once, from one specific geological pathway. It is a mineral that belongs to Earth’s hidden interior, revealed to us only through an extraordinary coincidence.

5. Tanohataite – Iwate Prefecture, Japan

Tanohataite is a fibrous manganese silicate mineral discovered in a single metamorphic rock formation in Japan’s Iwate Prefecture. Its structure is closely related to other silicate minerals, but its precise atomic arrangement and chemical composition set it apart as a distinct species.

This mineral formed under very specific metamorphic conditions involving manganese-rich sediments subjected to precise temperature and pressure regimes. Slight deviations in chemistry or metamorphic intensity would have produced a different mineral altogether.

Tanohataite’s uniqueness lies in its structural delicacy. Its crystal lattice represents a transitional form between known silicates, stabilized only under narrowly defined conditions. Despite extensive mineralogical surveys, no other location has reproduced this exact configuration.

In scientific terms, tanohataite illustrates how mineral species can emerge at the boundary between stability fields, occupying a narrow slice of geological possibility that may never open again.

6. Fingerite – Izalco Volcano, El Salvador

Fingerite is a copper oxychloride mineral formed in an environment so extreme that few minerals can survive there at all. It is found exclusively on the flanks of the Izalco volcano in El Salvador, where hot volcanic gases rich in chlorine and copper interact directly with atmospheric oxygen.

This mineral crystallizes from volcanic fumaroles at high temperatures, forming delicate blue-green crystals that are chemically unstable outside their formation environment. The specific mix of gas chemistry, temperature, and volcanic activity at Izalco appears to be unique.

Fingerite’s existence is fleeting on geological timescales. Changes in volcanic activity or gas composition could erase it entirely. Its presence is a snapshot of a moment in volcanic evolution, preserved only because mineralogists happened to observe it.

7. Zaccagnaite-3R – Carrara Marble Quarries, Italy

Zaccagnaite-3R is a layered carbonate hydroxide mineral found only in the famous marble quarries of Carrara, Italy. Its formation is linked to the interaction between hydrothermal fluids and magnesium-rich marble under precise chemical conditions.

The Carrara region has been quarried for millennia, yet zaccagnaite-3R remained undiscovered until modern analytical techniques revealed its distinct structure. Its rarity reflects how easily such a mineral could be overlooked, and how narrow its stability range truly is.

The mineral’s layered structure records subtle changes in fluid chemistry during metamorphism. Each layer is a geological sentence in a story written deep within the marble itself.

8. Putnisite – Western Australia

Putnisite is a vivid purple mineral composed of strontium, chromium, sulfur, and water. It is known only from a single occurrence in Western Australia, where oxidized chromium-bearing rocks interacted with sulfate-rich fluids.

The mineral’s color comes from chromium ions arranged in a precise coordination within the crystal structure. This arrangement is stable only within a narrow chemical window, explaining why putnisite has not been found elsewhere despite extensive exploration.

Putnisite’s discovery highlights how mineralogy continues to evolve. Even in a well-studied continent, Earth can still reveal a substance that exists nowhere else.

9. Hutcheonite – Yukon Territory, Canada

Hutcheonite is a complex carbonate mineral containing copper, magnesium, and aluminum. It has been identified from a single geological formation in Canada’s Yukon Territory.

Its formation required an unusual combination of metal-rich fluids interacting with carbonate rocks under controlled temperature conditions. Slight variations in fluid composition would have produced entirely different mineral species.

Hutcheonite’s uniqueness reflects the sensitivity of mineral formation to chemical ratios. Nature does not aim for repetition; it responds only to local conditions, even when the result is a mineral that appears only once.

10. Chladniite – Millbillillie Meteorite Fall, Australia

Chladniite is a phosphate mineral first identified in a meteorite that fell in Australia. Although extraterrestrial in origin, its recognition as a mineral species is tied to that single fall.

Its crystal structure reflects conditions in the early solar system, preserved in a fragment that survived atmospheric entry. No other confirmed terrestrial or meteoritic source has yielded the same mineral.

Chladniite blurs the boundary between Earth and space, reminding us that our planet is part of a larger mineralogical system extending beyond its surface.

11. Steinhardtite – Khatyrka Meteorite, Russia

Steinhardtite is a natural form of quasicrystal, a structure once thought impossible in nature. It was discovered in a meteorite fragment from a single location in Russia.

Its atomic arrangement exhibits order without periodic repetition, challenging classical crystallography. The extreme pressures and temperatures generated during extraterrestrial collisions appear necessary to form it.

Steinhardtite exists only because a precise cosmic event occurred and a fragment of that event reached Earth intact. Its singularity is both geological and cosmological.

Conclusion: Earth’s Singular Creations

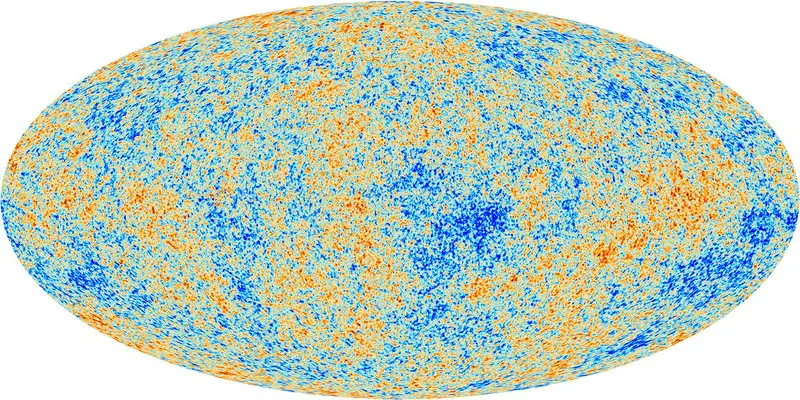

These eleven minerals represent moments when Earth—or the cosmos intersecting with Earth—briefly aligned chemistry, physics, and time in just the right way. They are reminders that rarity is not merely a matter of scarcity, but of uniqueness.

Each mineral exists because something happened once and never quite happened again. In studying them, we glimpse the immense creativity of natural processes and the fragile improbability behind even the smallest crystal. Earth is not only a planet of abundance; it is also a planet of singular stories, written in stone and found in only one place.