Life on Earth feels permanent when viewed from a human lifetime. Forests seem ancient, oceans eternal, and animals part of an unbroken chain stretching endlessly into the past. But the true history of life is far more violent and fragile. Again and again, the planet has been shaken by catastrophes so severe that most living species vanished in geological instants. These events are known as mass extinctions—moments when the web of life nearly unraveled, only to be rewoven in new and unexpected forms.

Mass extinctions are not just episodes of death. They are turning points. Each one reshaped evolution, erased dominant life forms, and opened the door for entirely new worlds to emerge. Without them, humans would not exist. Mammals would not rule the land. Even flowers, birds, and complex ecosystems owe their presence to these ancient disasters.

Here are ten of the most significant mass extinction events in Earth’s history, and the powerful forces that caused them.

1. The Ordovician–Silurian Extinction (About 444 Million Years Ago)

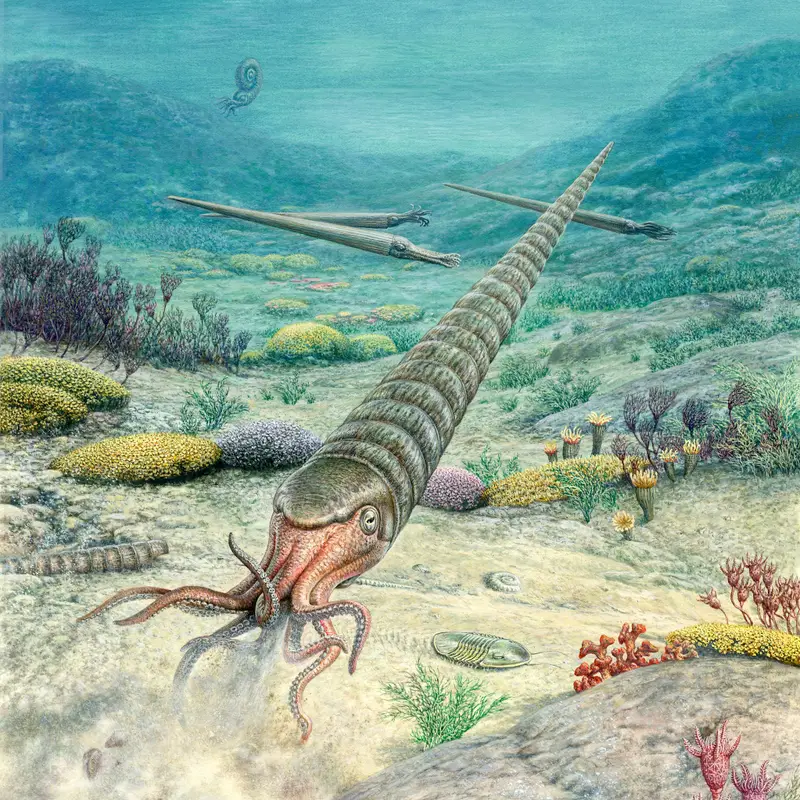

The first of the “Big Five” mass extinctions struck during the Ordovician period, when life thrived almost entirely in the oceans. Warm, shallow seas teemed with trilobites, brachiopods, early corals, and primitive fish. Biodiversity was soaring—until the climate abruptly turned against life.

This extinction was triggered by a dramatic ice age. Massive glaciers formed on the supercontinent Gondwana, locking up enormous amounts of water. Sea levels plummeted, draining shallow marine habitats where most species lived. As oceans shrank, ecosystems collapsed.

Ironically, when the ice age ended, the melting glaciers caused another wave of destruction. Sea levels rose rapidly, oxygen levels dropped, and previously exposed continental shelves were flooded with oxygen-poor water. This one-two punch wiped out an estimated 85 percent of marine species.

There were no dinosaurs to mourn, no forests to burn—only silent seas emptied of life. Yet from this devastation, new marine ecosystems slowly emerged, proving that even global catastrophe cannot permanently silence life.

2. The Late Devonian Extinction (About 375–359 Million Years Ago)

The Late Devonian extinction was not a single event but a prolonged crisis that unfolded over millions of years. During this time, life was making a bold move onto land. Early forests were spreading, and fish were diversifying into astonishing forms, including the ancestors of amphibians.

Then the oceans began to suffocate.

Evidence suggests widespread anoxia—a lack of oxygen in the seas—played a central role. As land plants expanded, they altered soil chemistry and increased nutrient runoff into oceans. This fueled massive algal blooms, which consumed oxygen as they decayed, creating vast dead zones.

At the same time, climate instability, cooling temperatures, and possibly volcanic activity added stress. Reef-building organisms were especially hard-hit, and many iconic armored fish vanished forever.

Approximately 75 percent of species disappeared. The Devonian seas never fully recovered their former diversity. But on land, vertebrates would eventually flourish, stepping into evolutionary opportunities created by extinction.

3. The Permian–Triassic Extinction (About 252 Million Years Ago)

This was the greatest extinction Earth has ever known. Often called “The Great Dying,” the Permian–Triassic extinction erased around 90 to 96 percent of marine species and roughly 70 percent of terrestrial vertebrates. Entire branches of life were cut off, never to return.

The leading cause was massive volcanic eruptions in what is now Siberia. These eruptions lasted for hundreds of thousands of years, releasing enormous quantities of carbon dioxide, methane, and toxic gases. Global temperatures soared. Oceans acidified. Oxygen levels collapsed.

Life faced a perfect storm of horrors: extreme heat, poisoned air, acidifying seas, and collapsing food chains. Forests burned and failed to regrow. Insects—the most resilient animals on Earth—suffered their only known mass extinction.

For millions of years afterward, the planet remained hostile. Recovery was slow and painful. Yet eventually, from the ashes of the Permian world, new life forms arose—including early dinosaurs and mammals.

4. The Triassic–Jurassic Extinction (About 201 Million Years Ago)

Just as life was recovering from the Great Dying, another catastrophe struck. The Triassic–Jurassic extinction cleared the stage for one of the most iconic groups in Earth’s history: the dinosaurs.

Once again, massive volcanic activity appears to be the primary culprit. As the supercontinent Pangaea began to break apart, colossal lava flows erupted, releasing greenhouse gases that caused rapid global warming. Ocean acidification and atmospheric instability followed.

Many large reptiles and amphibians vanished, along with numerous marine species. Dinosaurs, which were present but not yet dominant, survived and rapidly diversified into the newly emptied ecological niches.

This extinction did not end life—it reorganized it. The age of dinosaurs began not through superiority alone, but through survival in a time of planetary upheaval.

5. The Jurassic Marine Turnover (About 183 Million Years Ago)

Though not always counted among the “Big Five,” the early Jurassic experienced a significant extinction event that profoundly altered marine ecosystems. This crisis coincided with intense volcanic activity and rapid climate warming.

Oceans again suffered from widespread oxygen depletion. Many marine reptiles, ammonites, and plankton species declined or disappeared. Coral reefs were severely affected, and marine food webs were destabilized.

The causes mirror a recurring theme in extinction history: volcanic carbon emissions, warming climates, and oxygen-starved oceans. These patterns would repeat again and again, revealing just how sensitive life is to atmospheric change.

6. The Cretaceous–Paleogene Extinction (About 66 Million Years Ago)

This is the most famous mass extinction, etched into popular imagination by the image of a giant asteroid streaking across the sky. The impact, which struck near what is now the Yucatán Peninsula, released energy equivalent to billions of nuclear bombs.

Within hours, global wildfires raged. Dust and sulfur aerosols filled the atmosphere, blocking sunlight and plunging Earth into darkness. Photosynthesis collapsed. Temperatures dropped. Acid rain fell.

Dinosaurs—non-avian dinosaurs, to be precise—could not survive the sudden breakdown of ecosystems. Neither could many marine reptiles, ammonites, and plankton species. Around 75 percent of all species vanished.

Yet birds survived. Small mammals endured. From their survival came the rise of mammals, primates, and eventually humans. This extinction, devastating as it was, reshaped Earth into a world where intelligence could evolve.

7. The Paleocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum (About 56 Million Years Ago)

The Paleocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum, or PETM, was not marked by sudden impacts or volcanic apocalypses, but by rapid and extreme global warming. Over a few thousand years—a geological blink—global temperatures rose by 5 to 8 degrees Celsius.

The cause was a massive release of carbon into the atmosphere, likely from methane hydrates or volcanic activity. Oceans became warmer and more acidic. Many deep-sea organisms went extinct, unable to cope with the sudden change.

On land, mammals shrank in size, possibly as an adaptation to heat. Ecosystems shifted dramatically. While this event did not cause extinction on the scale of the Big Five, it serves as a powerful warning about the biological consequences of rapid climate change.

8. The Late Triassic Marine Extinction (Separate Marine Crisis)

In addition to the Triassic–Jurassic boundary extinction, the Late Triassic saw earlier marine crises that devastated ocean life. These events were driven by climate instability, fluctuating sea levels, and repeated volcanic episodes.

Marine invertebrates, reef builders, and plankton communities were especially vulnerable. The repeated stress prevented full ecological recovery, making life more susceptible to the final Triassic collapse.

This illustrates an important lesson: mass extinctions are often preceded by prolonged environmental stress, weakening ecosystems long before final collapse.

9. The Quaternary Megafauna Extinction (About 50,000–10,000 Years Ago)

Unlike ancient mass extinctions, this one unfolded alongside the rise of humans. Across continents, large animals—mammoths, saber-toothed cats, giant ground sloths, and many others—vanished.

Climate change at the end of the last ice age played a role, altering habitats and food availability. But evidence increasingly points to human activity as a major driver. Overhunting, landscape modification, and fire use placed enormous pressure on megafauna already struggling with environmental shifts.

This extinction reshaped ecosystems, altering vegetation patterns and predator-prey relationships. It was a quiet extinction compared to asteroid impacts, but no less transformative.

It was also the first mass extinction where a single species—us—played a central role.

10. The Holocene Extinction (The Sixth Mass Extinction)

We are living through it now.

The Holocene extinction, often called the Sixth Mass Extinction, is driven by human activity at a global scale. Habitat destruction, climate change, pollution, invasive species, and overexploitation are pushing species to extinction at rates far beyond natural background levels.

Forests fall. Coral reefs bleach. Species disappear before they are even discovered. Unlike past extinctions, this one is not caused by volcanic cataclysms or cosmic impacts, but by agriculture, industry, and consumption.

What makes this extinction uniquely tragic is awareness. For the first time in Earth’s history, a species understands what is happening—and has the power to change course.

What Mass Extinctions Reveal About Life and Survival

Mass extinctions are reminders that life on Earth is resilient but not invincible. The planet does not guarantee stability. Climate, chemistry, and geology can shift rapidly, pushing ecosystems beyond their limits.

Yet life always returns. After each extinction, evolution experiments anew. New species arise. New relationships form. The survivors shape the future.

Humans are both observers and participants in this story. We exist because of past extinctions—and now we are shaping one ourselves. Whether this chapter ends in collapse or transformation remains uncertain.

The history of mass extinctions is not just a record of death. It is a warning, a lesson, and a testament to the fragile beauty of life on a restless planet.