When a baby coos, gurgles, or babbles, it might seem like nothing more than adorable nonsense. Parents lean in, respond with smiles, exaggerated tones, or soft words, and the baby babbles again. Back and forth it goes—a playful, seemingly random exchange of sounds. But beneath that innocent chatter lies one of the most extraordinary processes in human development: the birth of language.

What makes this phenomenon even more fascinating is that humans are unusual in the animal kingdom for learning language in this way. For most creatures, sounds are instinctive, requiring little practice or feedback. Birds sing, wolves howl, monkeys shriek, but they do not fine-tune their voices through a learning process as humans do. Only a few other species, such as zebra finches and cowbirds, show anything close to this kind of vocal apprenticeship.

So why did humans evolve this unique pathway to communication? And how do our earliest exchanges of babble and response shape who we become? Recent studies of an unexpected little primate may offer surprising answers.

The Primate That Babble Like Us

In the dense forests of northeastern Brazil, tiny squirrel-sized monkeys called marmosets call out to one another with high-pitched whistles. Their voices carry through the trees, helping them stay connected when out of sight. For decades, these calls were thought to be little more than instinctual cries. But about ten years ago, researchers noticed something remarkable: baby marmosets don’t just cry—they babble.

Like human infants, newborn marmosets begin life with sputtering, uneven sounds. Gradually, with time and social interaction, their noisy cries evolve into the more structured whistles of adulthood. And just as in humans, the key to their development is feedback. The more responses young marmosets receive from adults, the faster they learn to “speak” in the language of their species.

Princeton neuroscientist Asif Ghazanfar and his colleagues were astonished by this discovery. It was one of the first signs that another primate, though separated from humans by around 40 million years of evolution, had stumbled upon a similar learning strategy. The realization sparked a new question: why would such distantly related species converge on the same unusual path to communication?

The Growing Brain and the Social World

The answer may lie in the brain’s timeline of development. A new study led by Renata Biazzi and published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences compared the brain growth of humans, marmosets, chimpanzees, and rhesus macaques from conception to adolescence. The results revealed something striking.

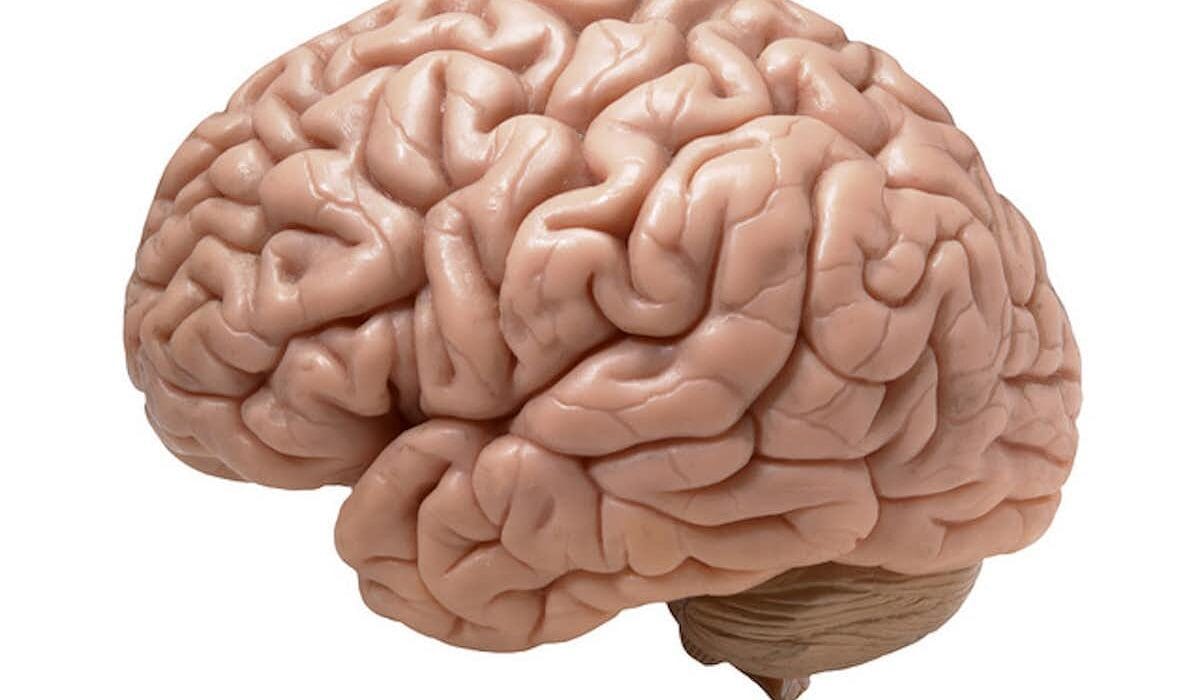

In both humans and marmosets, brain growth is unusually rapid during the earliest stages of life. Unlike chimpanzees or macaques, who do much of their brain development before birth, humans and marmosets undergo a surge of neural growth right around the time they enter the social world outside the womb.

This overlap—between rapid brain development and constant social interaction—creates the perfect environment for vocal learning. In both species, infants are surrounded by caregivers who respond to their every cry. Marmoset babies are raised not just by mothers but by fathers, siblings, and extended family members. Their constant cries demand constant attention, creating a feedback loop that shapes their communication.

The same is true for human infants. Every time a baby babbles and a parent responds, the brain wires itself a little more for language. Over time, random coos transform into purposeful sounds, laying the foundation for the words and sentences that will eventually shape thought, culture, and identity.

The Importance of Social Feedback

This discovery reinforces something parents have long intuited: talking to your baby matters. The babbling stage is not just cute—it is essential. By responding to their infant’s sounds, caregivers are not merely encouraging; they are actively teaching.

In fact, the research team built mathematical models to show how these early exchanges, combined with rapid brain growth, accelerate vocal development. The findings suggest that without this back-and-forth, infants might still learn to produce sounds, but at a slower pace and with less sophistication.

It’s not only about hearing language, then, but about participating in it. Human language, from its very beginnings, is a social act. Babies do not learn to speak in isolation; they learn in conversation—even if, at first, the conversation is mostly joyful nonsense.

Baby Talk Across Species

One fascinating next step in this line of research is whether adult marmosets, like human parents, use special “baby talk” when communicating with infants. Human caregivers naturally adjust their tone—higher pitch, slower rhythm, exaggerated intonation—when speaking to babies. This so-called “parentese” captures infants’ attention and makes it easier for them to mimic sounds.

If marmosets do something similar, it would further highlight the parallel paths our species have taken. And it might explain why these tiny monkeys, among all other primates, share this rare ability to learn through feedback during infancy.

Chimpanzees, our closest evolutionary relatives, do not babble in the same way. Their vocalizations appear early and require little practice, suggesting that while they may be brilliant in other domains of learning, language acquisition is not one of them. In this sense, humans and marmosets share a peculiar bond: both have brains and social systems that demand early, interactive communication.

The Human Story of Babble

Understanding babbling is about more than decoding baby noises. It reveals the roots of what makes us human. Language is the foundation of storytelling, teaching, cooperation, and culture. Every poem, every law, every love letter begins with those first babbled syllables.

The discovery that marmosets share this learning strategy suggests that the path to language may depend on a delicate balance of biology and environment. A rapidly growing brain alone is not enough—it must be met with a world ready to respond. Similarly, a nurturing environment cannot shape language without the brain’s remarkable capacity to learn.

This marriage of growth and interaction highlights how deeply social we are as a species. From our earliest breaths, we are wired for connection. The voices that answer our cries not only comfort us but shape the way we will one day speak, think, and connect with others.

Beyond Babble: The Future of Research

Scientists are only beginning to uncover the full story of how language emerges from babbling. Future studies may reveal how different kinds of feedback influence learning, or whether variations in early experiences affect language skills later in life.

There are also profound implications for understanding developmental disorders. If the timing of brain growth and social interaction is critical, then disruptions in this process might explain why some children struggle with speech and communication. Insights from marmosets could eventually guide therapies or interventions that help children find their voices.

The Symphony of First Sounds

The next time you hear a baby babble, pause for a moment. Those sounds are not meaningless—they are music in the making, the first notes of the symphony of language. And when a parent responds, they are not just encouraging but shaping a future speaker, thinker, and storyteller.

What begins as a playful exchange of nonsense syllables grows into the most powerful tool humans have ever known: the ability to communicate ideas, share knowledge, and connect across generations.

Babbling is not simply the start of speech—it is the first act in the lifelong human drama of conversation, collaboration, and community. From the forests of Brazil to the nurseries of the world, the voices of infants remind us that language is not just something we learn. It is something we are born to share.

More information: Renata B. Biazzi et al, Altricial brains and the evolution of infant vocal learning, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2025). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2421095122