The human brain is the most complex organ in the known universe. Within its three-pound mass lie our thoughts, emotions, dreams, fears, memories, and consciousness itself. But just as any other part of the body can malfunction, so too can the mind. When it does, the field that steps in to understand, diagnose, and treat its disorders is psychiatry.

For centuries, mental health has walked a thin line between science and stigma, enlightenment and misunderstanding. Today, psychiatry stands as a vital medical discipline—one that is continually evolving, often controversial, and deeply tied to how we define what it means to be human.

But what exactly is psychiatry? How does it differ from psychology? What tools do psychiatrists use to treat mental illness? Why is the field often misunderstood or mistrusted? And where is it headed in the future?

This article takes a comprehensive and engaging look at psychiatry—not just as a medical specialty, but as a human endeavor to make sense of the mind and to heal it when it suffers.

The Origins of Psychiatry: From Superstition to Science

The roots of psychiatry stretch far back into antiquity, but they didn’t always resemble what we now recognize as medical practice. In ancient civilizations—Babylon, Egypt, Greece, India, and China—mental illness was often seen as a spiritual or supernatural affliction. People who behaved strangely were thought to be possessed by demons, punished by gods, or cursed by witches.

Treatments were harsh and mystical: exorcisms, prayers, potions, and, at times, isolation or even execution.

Yet some ancient thinkers hinted at a biological basis for mental disturbances. Hippocrates, the father of modern medicine, proposed that mental illness resulted from imbalances in bodily fluids or “humors.” Though scientifically flawed, this idea marked a shift from supernatural to naturalistic explanations.

Fast-forward to the 18th and 19th centuries, and we see the birth of what could be called proto-psychiatry. Enlightenment thinkers began to view mental illness as a condition requiring compassion and care, not punishment. Institutions called “asylums” emerged across Europe and America. Though often overcrowded and poorly managed, they represented a social shift in attitudes.

In the 1800s, Philippe Pinel in France and William Tuke in England championed the “moral treatment” movement—emphasizing kindness, structured environments, and meaningful work as therapeutic tools.

By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, psychiatry began to formalize as a medical discipline. Theories diversified—from Freudian psychoanalysis to early biological models. But it would take the 20th century’s scientific revolutions to truly establish psychiatry as a core pillar of modern medicine.

Defining Psychiatry: The Medicine of the Mind

At its core, psychiatry is the branch of medicine that deals with the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of mental, emotional, and behavioral disorders.

A psychiatrist is a medical doctor (MD or DO) who specializes in mental health. This sets psychiatrists apart from psychologists, who typically hold a PhD or PsyD and are not medical doctors. While both professions may offer therapy, only psychiatrists can prescribe medications.

Psychiatry sits at the intersection of biology, psychology, and social science. It doesn’t treat just the mind or just the brain—but both, recognizing that the human experience cannot be reduced to biology alone, nor can it be fully understood without it.

Psychiatrists are trained to assess complex interactions between:

- Neurobiology (brain chemistry, structure, and function)

- Behavior and cognition

- Emotional regulation

- Genetics and family history

- Life experiences, trauma, and environment

- Social, cultural, and spiritual context

In this way, psychiatry aims to be holistic, although it is often criticized for favoring one explanatory model over others—something we’ll explore later in this article.

The Spectrum of Mental Illness

Mental illness isn’t just one thing. It’s a spectrum of conditions that range from mild anxiety to severe psychosis. Each condition manifests differently, responds differently to treatment, and carries a unique social and emotional weight.

Here are some of the major categories of mental illness that psychiatrists diagnose and treat:

Mood Disorders

These include depression, bipolar disorder, and dysthymia. They affect emotional state and energy levels. Someone with major depressive disorder may feel overwhelming sadness, hopelessness, and fatigue, while someone with bipolar disorder experiences swings between depression and mania.

Anxiety Disorders

Generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, social anxiety disorder, phobias, and obsessive-compulsive disorder fall into this group. They involve excessive fear or worry that disrupts daily life.

Psychotic Disorders

The most well-known is schizophrenia. These disorders involve distorted thinking, hallucinations (seeing or hearing things that aren’t there), and delusions (false beliefs).

Personality Disorders

These are long-term patterns of thinking and behavior that are inflexible and problematic. Examples include borderline personality disorder, narcissistic personality disorder, and antisocial personality disorder.

Neurodevelopmental Disorders

Conditions like autism spectrum disorder and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) usually begin in childhood and affect cognitive, social, and behavioral functioning.

Trauma- and Stressor-Related Disorders

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is the best-known in this category. It arises after exposure to life-threatening events or severe psychological trauma.

Substance Use Disorders

These involve dependence on alcohol, drugs, or other substances, often alongside other mental illnesses—a phenomenon known as dual diagnosis.

Eating Disorders

Anorexia, bulimia, and binge-eating disorder are psychiatric illnesses with serious medical consequences.

These categories are not fixed, and many people have symptoms that span multiple diagnoses. This complexity is one reason psychiatry continues to evolve and remains the subject of intense debate.

The Psychiatric Diagnostic Process

Psychiatrists don’t rely on X-rays or blood tests to diagnose mental illness (though these may be used to rule out other conditions). Instead, they rely on a clinical interview, history-taking, observations, and structured assessments.

The most widely used guide is the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), currently in its fifth edition (DSM-5-TR). This manual outlines the criteria for diagnosing every recognized psychiatric condition.

A typical psychiatric evaluation includes:

- Chief complaint: Why is the patient seeking help?

- History of present illness: When did symptoms begin? How have they changed?

- Psychiatric history: Previous diagnoses, hospitalizations, or treatments.

- Medical history: Including neurological or chronic physical conditions.

- Family history: Mental illness or substance use in close relatives.

- Social history: Relationships, employment, lifestyle, trauma, and support systems.

- Mental status examination (MSE): A structured evaluation of the patient’s appearance, behavior, mood, thought process, cognition, and insight.

Based on this information, a psychiatrist formulates a diagnosis and treatment plan tailored to the individual.

Modes of Treatment: Tools in the Psychiatrist’s Toolkit

Treatment in psychiatry is highly individualized. Some patients may need brief therapy during a stressful period; others require lifelong medication and support. Broadly speaking, treatment falls into several categories:

Pharmacotherapy

Medications are among the most powerful tools in psychiatry. They don’t “cure” mental illness, but they can relieve symptoms, improve function, and reduce relapse.

Common classes of psychiatric medications include:

- Antidepressants (e.g., SSRIs, SNRIs): Used for depression, anxiety, PTSD, and OCD.

- Antipsychotics: Treat schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and severe agitation.

- Mood stabilizers (e.g., lithium, valproate): Often used in bipolar disorder.

- Anxiolytics: Benzodiazepines for short-term anxiety or panic.

- Stimulants: Used to treat ADHD.

- Sleep aids: Sometimes used short-term in mood and anxiety disorders.

Each medication carries risks and side effects. Psychiatrists carefully balance potential benefits with side effects and often adjust doses over time.

Psychotherapy

While psychologists and counselors often provide therapy, many psychiatrists also receive training in psychotherapeutic techniques.

Therapy is not just “talking about your problems.” It’s a structured and evidence-based method to change thought patterns, behaviors, and emotional responses.

Major approaches include:

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT): Identifying and altering harmful thought patterns.

- Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT): Focused on emotion regulation and mindfulness.

- Psychodynamic Therapy: Rooted in Freudian theory; explores unconscious conflicts.

- Interpersonal Therapy (IPT): Emphasizes relationships and communication.

- Supportive Therapy: Offers empathy, guidance, and reassurance.

Some forms are short-term; others may last years.

Electroconvulsive Therapy (ECT)

ECT is a medical procedure used primarily for severe depression that hasn’t responded to other treatments. It involves inducing controlled seizures using electrical currents under anesthesia.

Despite its controversial history, modern ECT is safe, effective, and often life-saving—especially in cases of suicidal depression or treatment-resistant mood disorders.

Emerging Treatments

New frontiers in psychiatry include:

- Ketamine therapy: A rapid-acting antidepressant effect.

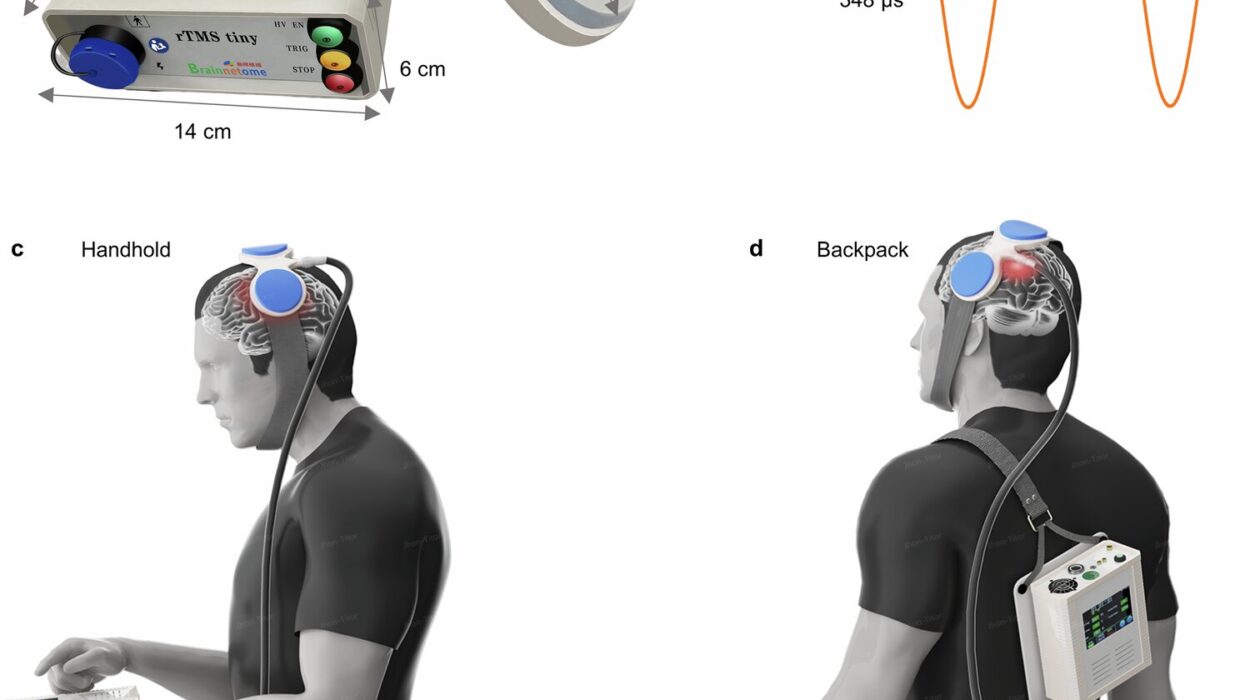

- Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS): Non-invasive brain stimulation.

- Psychedelic-assisted therapy: With substances like psilocybin or MDMA.

- Digital therapy apps: For guided CBT and mindfulness.

As research advances, psychiatry’s toolbox continues to expand.

Challenges in Psychiatry: Controversies and Critiques

Psychiatry is one of the most contested fields in medicine. It has made enormous strides—but also faces deep ethical, scientific, and societal questions.

The Stigma of Mental Illness

Despite growing awareness, mental illness still carries stigma. Many people avoid seeking help due to fear of being labeled, misunderstood, or judged.

This stigma can be internal (shame, guilt) or external (discrimination, exclusion). It affects everything from employment to relationships to access to care.

Psychiatrists often serve as advocates, working to destigmatize mental illness and promote mental wellness as integral to health.

The Mind-Body Problem

A persistent tension in psychiatry is whether mental illness is best viewed as a brain disease or a psychosocial phenomenon.

Biological psychiatry emphasizes genes, neurotransmitters, and brain circuits. Psychodynamic or social models emphasize trauma, culture, and relationships.

Critics argue that an over-reliance on medications ignores social determinants of health—poverty, abuse, inequality—that play a huge role in mental wellness.

The best psychiatrists navigate both worlds—recognizing the brain’s role while never forgetting the patient’s humanity.

Diagnostic Challenges

Unlike cancer or diabetes, there are no blood tests for depression or imaging scans for schizophrenia. Diagnosis is based on behavior, self-report, and clinical judgment. This leads to concerns about:

- Overdiagnosis or underdiagnosis

- Medicalizing normal emotions

- Cultural bias in diagnostic criteria

- Pharmaceutical influence on diagnosis trends

Psychiatry strives to be scientific—but its subject matter, the human mind, resists easy categorization.

Psychiatry and the Future of Mental Health

As neuroscience advances, psychiatry is poised for transformation.

In the near future, we may see:

- Precision psychiatry: Tailoring treatment to a patient’s genes and brain structure.

- AI-powered diagnostics: Using machine learning to predict illness.

- Biomarkers for mental illness: Objective tests to guide diagnosis and treatment.

- Global mental health: Scaling psychiatric care to underserved populations.

- Preventive psychiatry: Focusing on resilience and early intervention.

But even as technology changes, psychiatry will always rest on a core truth: mental health is deeply personal. It is not just about brain chemistry or behavior—it’s about suffering, healing, connection, and the human experience.

Conclusion: Psychiatry as a Journey, Not a Destination

Psychiatry is not perfect. It wrestles with ambiguity, grapples with ethics, and evolves with society. But at its heart, it is a discipline born of compassion—a medical field that dares to treat not the broken leg or failing heart, but the wounded mind.

In doing so, it confronts our deepest fears and hopes. It affirms that mental illness is real, treatable, and never a source of shame. It reminds us that healing is possible, that change is achievable, and that even in the darkest corners of the psyche, there is light.

Whether you are a patient, a family member, a student, or simply curious—understanding psychiatry is understanding part of what it means to be human.

And that journey is just beginning.