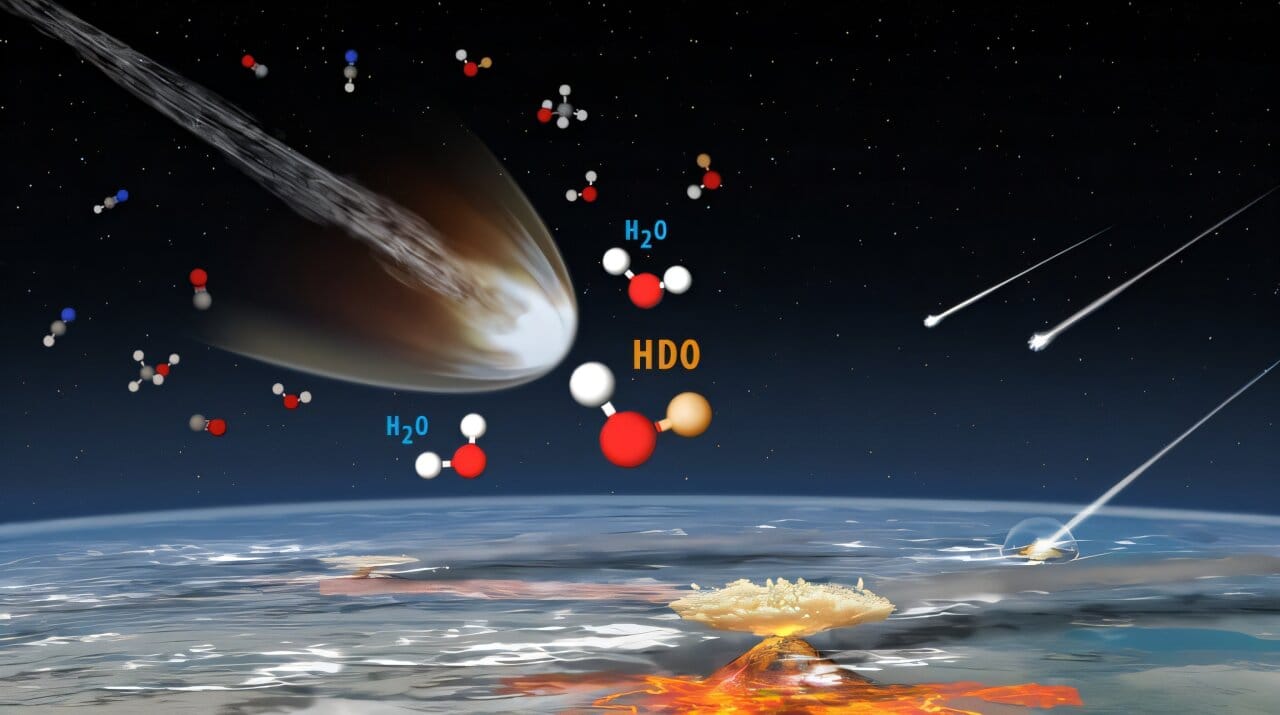

In the cold, dark reaches of our solar system, comets drift like frozen time capsules, preserving secrets from the dawn of planetary history. Now, an international team of scientists has cracked open one of these icy vaults — and found that the water within is strikingly similar to that in Earth’s oceans.

The discovery, made using two of the world’s most advanced telescopes, adds powerful new evidence to a long-debated theory: comets may have been the celestial couriers that brought water — and perhaps even the raw materials for life — to our young planet billions of years ago.

First-Ever Detailed Water Mapping in a Comet

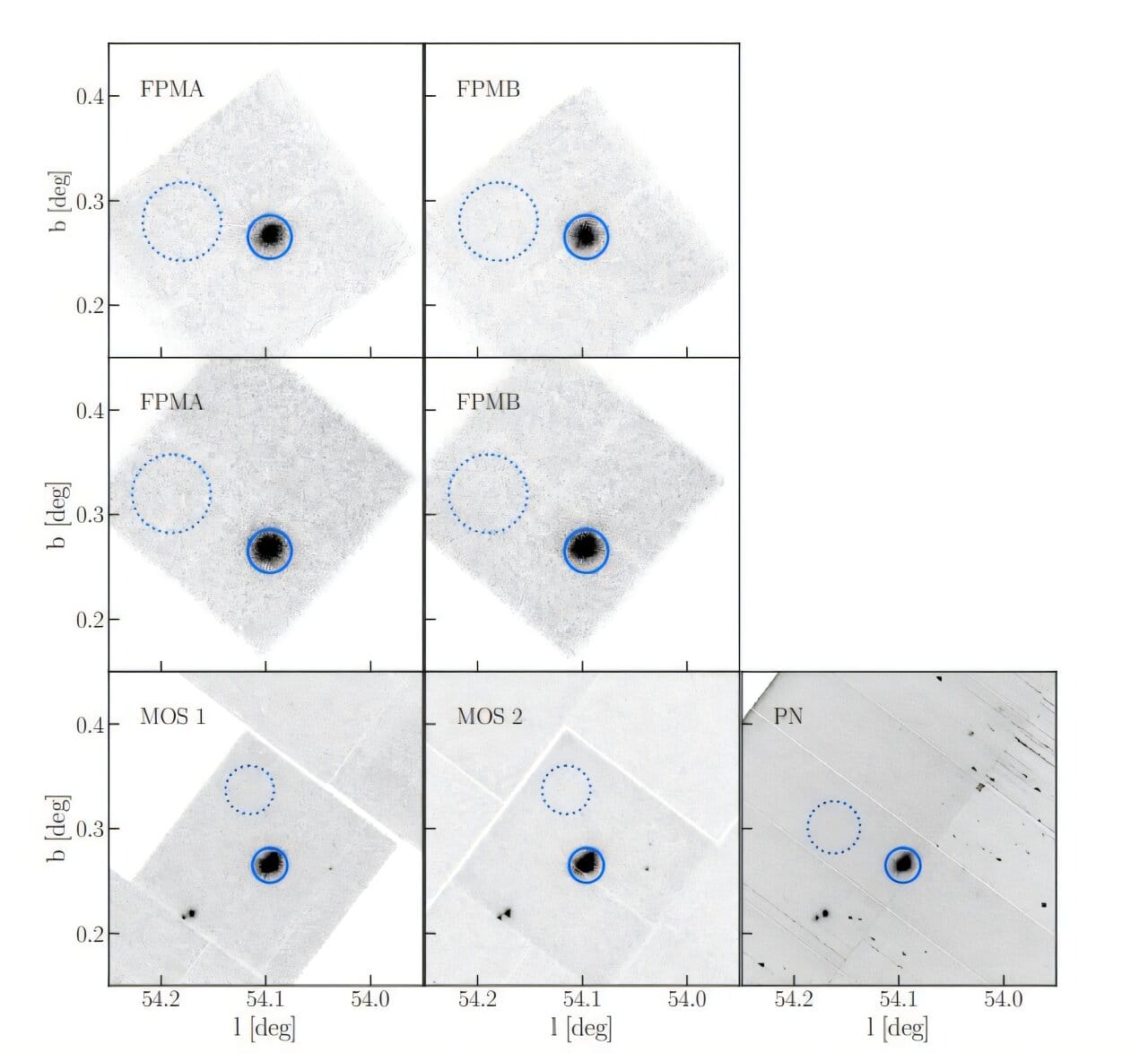

The focus of this groundbreaking research was comet 12P/Pons-Brooks, a rare “Halley-type” comet that swings through the inner solar system only once every 71 years. As it approached the Sun, scientists used the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) in Chile to map two distinct forms of water in its coma — the shimmering cloud of gas surrounding its icy nucleus.

The first was ordinary water (H₂O), the same molecule that fills our oceans and rivers. The second was “heavy water” (HDO), in which one of the hydrogen atoms is replaced by a heavier isotope called deuterium.

“By measuring the ratio of deuterium to hydrogen in comet water, we can create a kind of chemical fingerprint,” explained Martin Cordiner of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, the study’s lead author. “This fingerprint tells us where that water may have come from and how it has evolved over the 4.5-billion-year history of the solar system.”

Matching the Oceans of Earth

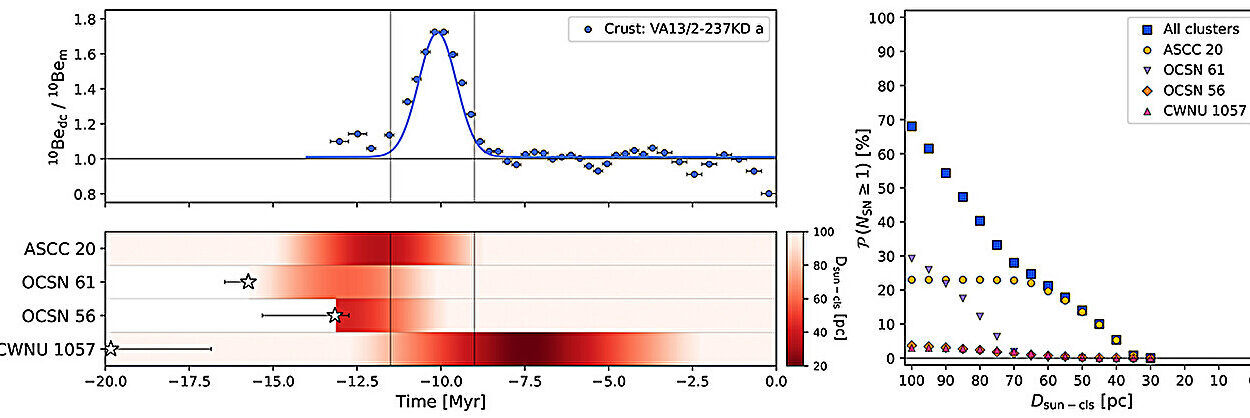

The results stunned the researchers. The deuterium-to-hydrogen ratio (D/H) in 12P/Pons-Brooks measured (1.71±0.44)×10⁻⁴ — virtually identical to the D/H ratio of Earth’s oceans. Even more remarkably, it’s the lowest ever measured in a Halley-type comet, a category previously known for having higher, less Earth-like values.

“This is the strongest evidence yet that at least some comets carried water with the same isotopic signature as Earth’s,” Cordiner said. “It strongly supports the idea that comet impacts may have been an important source of our planet’s water, making Earth a more hospitable place for life to develop.”

Why This Changes the Debate

For decades, scientists have debated whether comets or asteroids were the primary source of Earth’s water. Many earlier comet measurements showed D/H ratios far higher than Earth’s, suggesting they weren’t a major contributor. But this new finding disrupts that view.

Halley-type comets, like 12P/Pons-Brooks, are particularly intriguing because they originate from the Kuiper Belt — a distant region beyond Neptune — and spend most of their lives far from the Sun. That means their icy interiors are exceptionally well-preserved, offering a more pristine record of the solar system’s early chemistry.

Peering into the Heart of a Comet

This breakthrough was possible because ALMA’s unparalleled sensitivity allowed the team to detect heavy water in the innermost regions of the coma — the area closest to the comet’s nucleus — for the first time in history.

The observations were then combined with infrared data from NASA’s Infrared Telescope Facility (IRTF) in Hawaii, giving researchers a fuller picture of the comet’s chemistry.

“Mapping both H₂O and HDO tells us these gases are coming directly from the ices within the nucleus,” explained Stefanie Milam, a co-author of the study. “That’s critical, because it means we’re measuring the comet’s original composition — not water that’s been altered by sunlight or chemical reactions in the coma.”

A Window Into Our Own Beginnings

Beyond the chemistry, the findings carry a deep emotional resonance. They connect our oceans, the cradle of all known life, to icy bodies born billions of miles away, long before Earth even existed.

The notion that the water we drink — and the water that flows through our veins — might have once been locked inside a comet orbiting the Sun in the solar system’s infancy is a reminder of our cosmic heritage.

“These comets are relics of the building blocks from which our solar system formed,” Cordiner reflected. “In a very real sense, they are part of our family history.”

Looking Ahead

The team’s results, published in Nature Astronomy, are expected to spark new interest in targeted comet missions. Future spacecraft could directly sample Halley-type comet ices to confirm their role in delivering water and organics to Earth.

For now, 12P/Pons-Brooks continues its journey through the solar system, slowly retreating into the dark after its 2024–2025 appearance. It will not return for another seven decades — but it has already left us with a message: the origins of our oceans, and perhaps life itself, may be written in the frozen heart of a wandering comet.

More information: M. A. Cordiner et al, A D/H ratio consistent with Earth’s water in Halley-type comet 12P from ALMA HDO mapping, Nature Astronomy (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41550-025-02614-7