Long before space telescopes pierced the veil of the cosmos, before humanity launched instruments to orbit the Earth or even dreamt of setting foot on the Moon, a faint smudge of light caught the eye of an 18th-century astronomer. It was 1781, and Pierre Méchain, a French surveyor and avid celestial observer, turned his telescope toward the constellation Virgo. There, at the boundary of visibility, he recorded what he described as a nebulous object—a ghostly shimmer of unresolved starlight.

Unbeknownst to Méchain, he had just recorded what would become one of the most iconic galaxies in the night sky. His friend and collaborator, Charles Messier, whose famous catalog of celestial objects aimed to help comet hunters avoid confusing fuzzy galaxies with true comets, did not include the object at first. It was only in 1921, nearly 140 years later, that this bright elliptical galaxy, already beloved by amateur astronomers, was formally added to the Messier catalog as Messier 104—the Sombrero Galaxy.

What made it so distinctive was immediately obvious even to those with backyard telescopes: it appeared like a luminous disk with a dark band cutting through it, resembling a wide-brimmed hat. The striking silhouette earned it the nickname “Sombrero,” and that visual drama was only the beginning of the galaxy’s story.

A Stellar Giant Seen From the Side

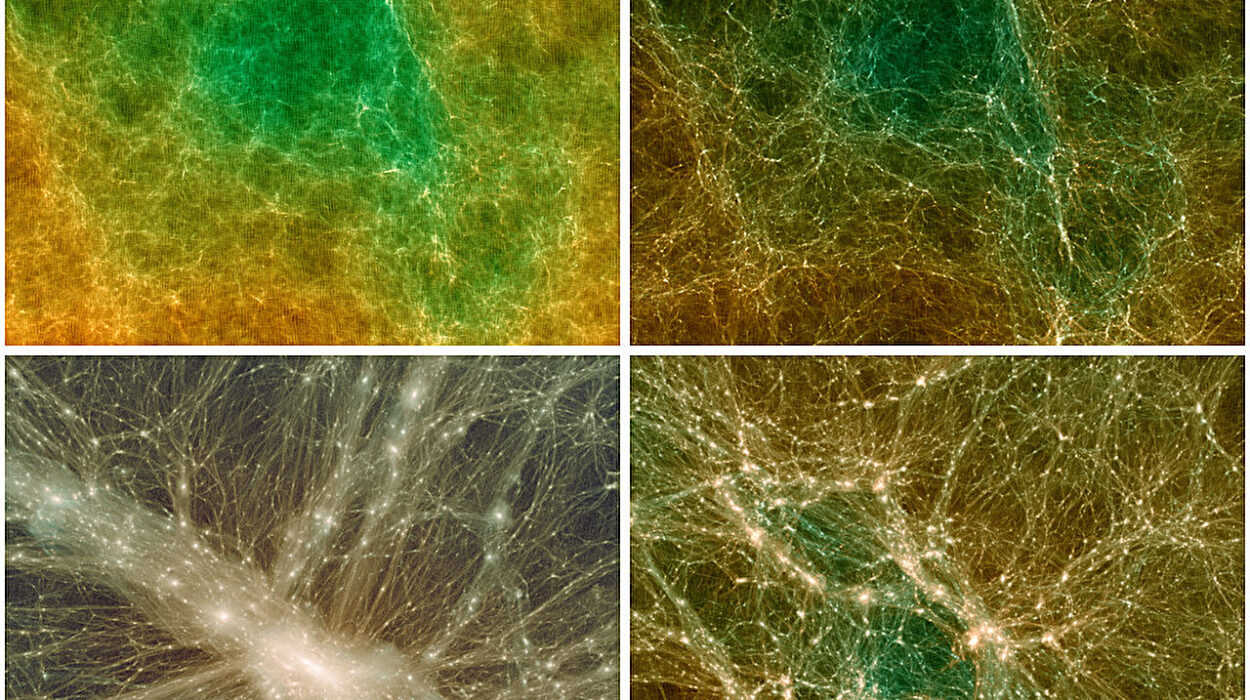

The Sombrero Galaxy lies some 30 million light-years away—close enough for Earth-based and space-based telescopes to resolve significant detail, yet far enough that even its light has taken longer to reach us than the earliest cave paintings. This galaxy sits near the outer fringe of the Virgo Cluster, a massive collection of over 1,300 galaxies bound together in a vast gravitational web.

From our vantage point on Earth, the Sombrero appears edge-on, or nearly so. In truth, our view is tilted just six degrees off from its true equator. That subtle angle gives astronomers a spectacular side-on view of its brilliant central bulge and the sharply defined dust lane slicing through the galaxy’s disk. The contrast between the glowing heart and the inky veil of dust is what makes the Sombrero one of the most photogenic galaxies ever observed.

But what looks serene on the surface turns out to mask an inner history of violence, turbulence, and transformation. The Sombrero Galaxy is no quiet relic—it’s a survivor of galactic chaos.

A New Lens: Webb’s Infrared Gaze on a Classic Galaxy

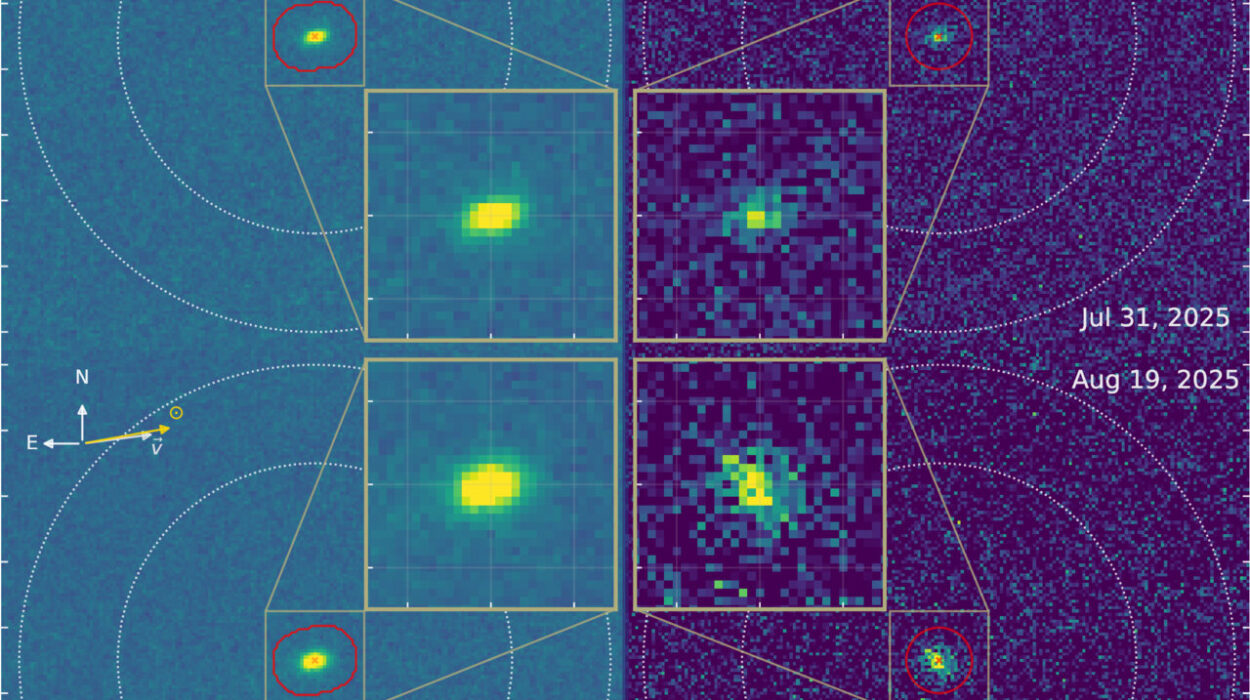

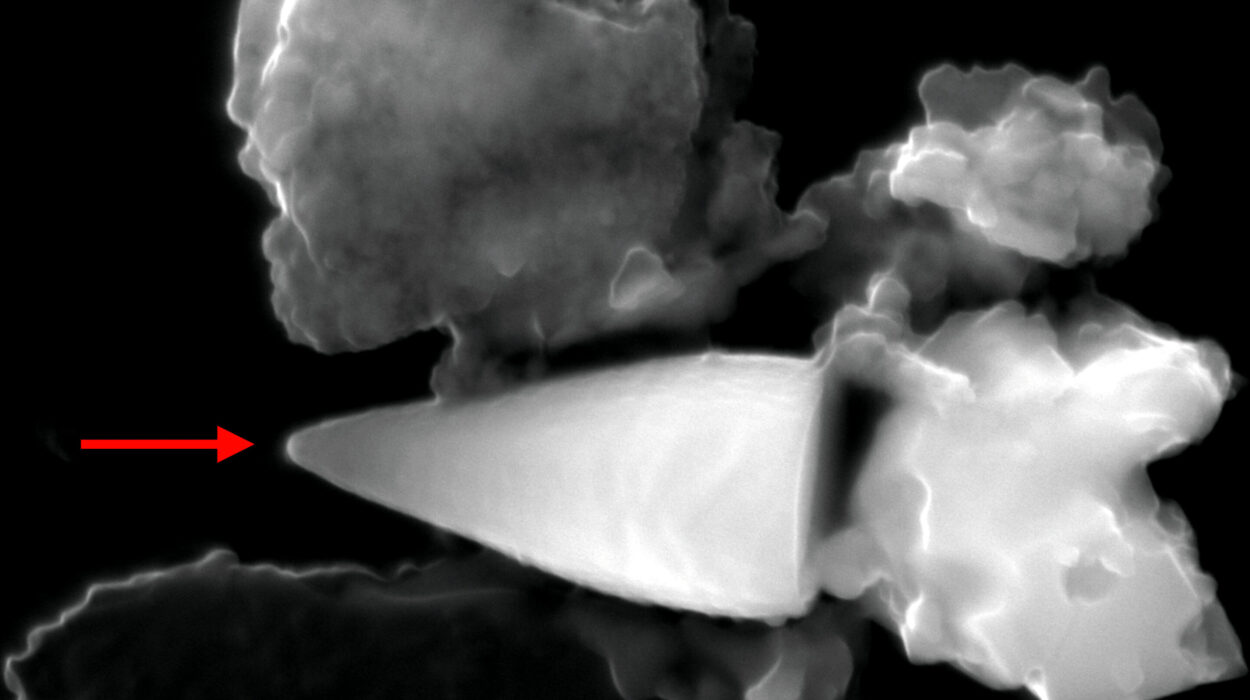

In late 2024, the James Webb Space Telescope—the most advanced space observatory ever built—turned its powerful gaze toward the Sombrero. Earlier mid-infrared observations had already revealed tantalizing details, but in a more recent campaign, Webb captured the galaxy in near-infrared wavelengths using its NIRCam (Near-Infrared Camera) instrument.

The resulting image peered past the dark dust lane that typically obscures much of the galaxy’s starlight. In visible light, captured by telescopes like Hubble, this dust appears as a dramatic black band cutting across the disk. But near-infrared light penetrates much of this obscuring material, allowing astronomers to view the tightly packed stars in the galaxy’s central bulge in striking detail.

The dusty regions that seem opaque in visible wavelengths become semi-transparent in the infrared. Longer wavelengths can slip between the dense clumps of particles, revealing the underlying architecture of the galaxy. In fact, at mid-infrared wavelengths, we don’t just see through the dust—we see it glowing, warmed by the stars that light it from within.

Unmasking a Turbulent Past

The Sombrero Galaxy’s smooth, symmetrical appearance is deceptively tranquil. Like a cathedral standing firm after a storm, its exterior offers few clues to the turbulence it has weathered. But astronomers are now uncovering signs of a dramatic history of galactic mergers.

Several clues point to past collisions and cosmic cannibalism. One of the most striking is the tilted shape of the inner disk. Although the galaxy appears to be viewed edge-on, a closer look reveals that the innermost part of the disk is warped inward, like the lip of a funnel. This structural distortion could be the scar of a past merger—an ancient cosmic collision that flung stars into new orbits and twisted the geometry of the galaxy’s core.

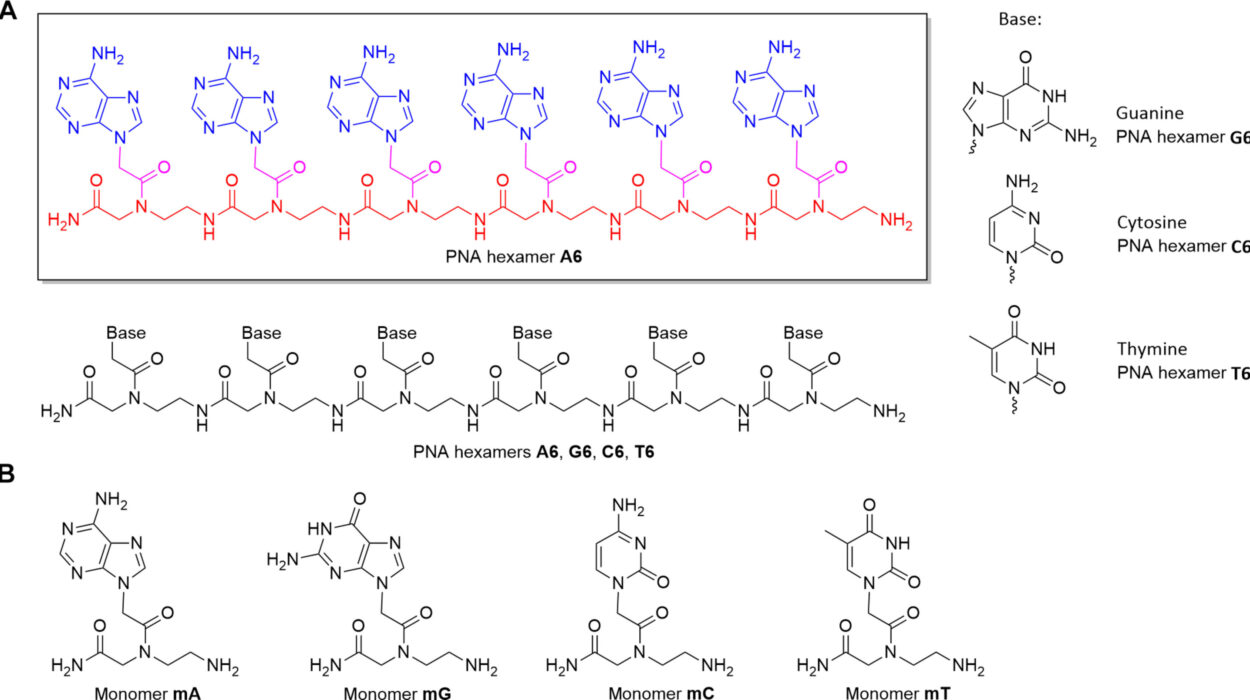

In addition, astronomers have detected peculiarities in the population of globular clusters orbiting the Sombrero. These clusters—dense swarms of ancient stars bound by gravity—typically form from a single batch of gas and dust and should, in theory, have similar chemical compositions. But the Sombrero’s 2,000 globular clusters tell a different story. Spectroscopic analysis shows that their stars possess wildly divergent chemical fingerprints, suggesting that they came from different parent galaxies. This patchwork composition strongly supports the theory that the Sombrero has absorbed other galaxies over billions of years.

Such mergers are a natural part of galactic evolution. The universe is dynamic, not static; galaxies are constantly in motion, and over cosmic timescales, collisions are inevitable. While violent, these events are also creative, fueling bursts of star formation and reshaping the identities of galaxies like the Sombrero.

Stars That Glow in Different Lights

One of the great strengths of the James Webb Space Telescope is its ability to resolve individual stars within and beyond galaxies. In the Sombrero’s near-infrared image, Webb captured a sprinkling of red giants—cool, dying stars that have swelled to enormous sizes. Though relatively cold compared to blue stars, their vast surfaces emit enough infrared radiation to make them glow brightly in Webb’s vision.

Interestingly, many of the smaller, hotter, blue stars fade from view in the mid-infrared images. These stars radiate more strongly in shorter wavelengths, such as ultraviolet and visible light, and are thus more apparent in Hubble’s images. In contrast, Webb’s instruments reveal a hidden population of stars and structures that were previously invisible.

Webb’s sharp resolution also brings into focus background galaxies scattered across the cosmos behind the Sombrero. Their diverse shapes and colors serve as more than eye candy; they act as cosmic signposts, offering astronomers clues about their distance, age, and composition. Redder galaxies are typically farther away, their light stretched by the expansion of the universe, while bluer ones may lie closer or be undergoing active star formation.

These background galaxies, captured incidentally in the frame, remind us of the Sombrero’s context—not as an isolated island of stars, but as part of a vast and dynamic cosmic web stretching across billions of light-years.

Galactic Mass and the Weight of Light

The Sombrero Galaxy may seem like a modest object at first glance, but its mass is staggering. Astronomers estimate that it contains the equivalent of 800 billion suns, making it significantly more massive than our own Milky Way Galaxy. This mass isn’t just in stars—it includes dark matter, gas, dust, and perhaps a supermassive black hole at its center.

In fact, radio and x-ray observations have hinted at the presence of a central black hole with a mass exceeding 1 billion solar masses, one of the largest known. The energy from this black hole, though currently dormant or faint, could have once powered an active galactic nucleus, lighting up the core with tremendous radiation and driving matter outward into the galaxy’s halo.

Though now quiet, this core may still harbor secrets. Infrared observations from Webb and future x-ray data could reveal new details about the central engine that shaped the Sombrero’s evolution.

Layers of Time in Dust and Light

Galaxies like the Sombrero are more than collections of stars; they are archives of cosmic time. The distribution of stars in its bulge, disk, and halo reflects billions of years of formation history. Dust lanes indicate where gas cooled and condensed to form stars. Globular clusters tell stories of early epochs, perhaps even tracing the remnants of galaxies long absorbed.

The key to unlocking these stories lies in observing at multiple wavelengths. While visible light shows us the bright face of galaxies, infrared light unveils their skeletons—the structure hidden beneath layers of dust. It penetrates what the eye cannot, showing us stars in their infancy, gas swirling in formation, and ancient giants glowing in their final acts.

By combining the views from Hubble’s optical clarity and Webb’s infrared depth, astronomers now wield a more complete toolkit than ever before. The Sombrero Galaxy becomes not just a beautiful object, but a case study in galactic archaeology.

Looking Ahead: What the Sombrero Still Holds

Despite centuries of observation, the Sombrero Galaxy still guards many of its secrets. Its central black hole’s full influence, the exact number of past mergers, and the role of its dust and gas in future star formation all remain active areas of research.

Future telescopes, such as the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope and upcoming radio arrays like the Square Kilometre Array, may probe even deeper into its past and peer with unprecedented sensitivity into its halo and central regions. These instruments could detect the faint echoes of past collisions, trace gas inflows and outflows, and help astronomers build a more detailed timeline of how galaxies evolve.

In this way, the Sombrero continues to play its dual role—as both a cosmic icon and a scientific enigma. It reminds us that even the most familiar celestial objects can yield new insights under new light.

Conclusion: The Cosmic Hat with a Turbulent Heart

The Sombrero Galaxy, once a mysterious smudge in Méchain’s telescope, now stands revealed in unprecedented detail. Thanks to the James Webb Space Telescope’s infrared vision, what was once hidden beneath dust is now illuminated with clarity and depth.

Behind its calm exterior lies a narrative of collision, survival, and rebirth. Its warped inner disk, its chemically diverse globular clusters, and its massive heart all point to a past shaped by violent mergers and cosmic transformation. Yet it endures—quietly orbiting the center of the Virgo Cluster, its glowing bulge and dark dust lane continuing to inspire observers, both amateur and professional.

The Sombrero Galaxy is a portrait of the universe’s paradoxes: order emerging from chaos, beauty born of violence, and the steady glow of stars illuminating stories billions of years old.