On a remote mountaintop in southern Spain, under the crisp darkness of the Calar Alto sky, a telescope stares silently at the night. Inside, a high-precision instrument named CARMENES listens—not for sound, but for the faintest wobble in starlight. That wobble, caused by a star being tugged ever so slightly by orbiting planets, is a cosmic whisper. And recently, it spoke volumes.

Astronomers from Heidelberg University, leading a team of international scientists, have uncovered compelling evidence that Earth-like planets may be far more common than previously thought—especially around the galaxy’s smallest stars. Drawing on years of data from the CARMENES project, they’ve identified four new exoplanets, including three that closely resemble our own planet in mass and orbit.

But the real story is bigger: tiny stars—often overlooked in earlier searches—could be teeming with small, rocky planets, many potentially sitting in the habitable zone, where liquid water might exist. The results, published in Astronomy & Astrophysics, may redefine where we look for life beyond Earth.

The Little Stars with Big Potential

These stars, known as M-dwarfs, are cosmic underdogs. With less than half—and often just a tenth—of the mass of our Sun, they burn dimly, live long, and make up the majority of stars in the Milky Way. They’re hard to study with traditional techniques because they’re faint. But their low mass makes it easier to detect the gravitational tugs of small orbiting planets—if you have the right tools.

And CARMENES was built for just this purpose.

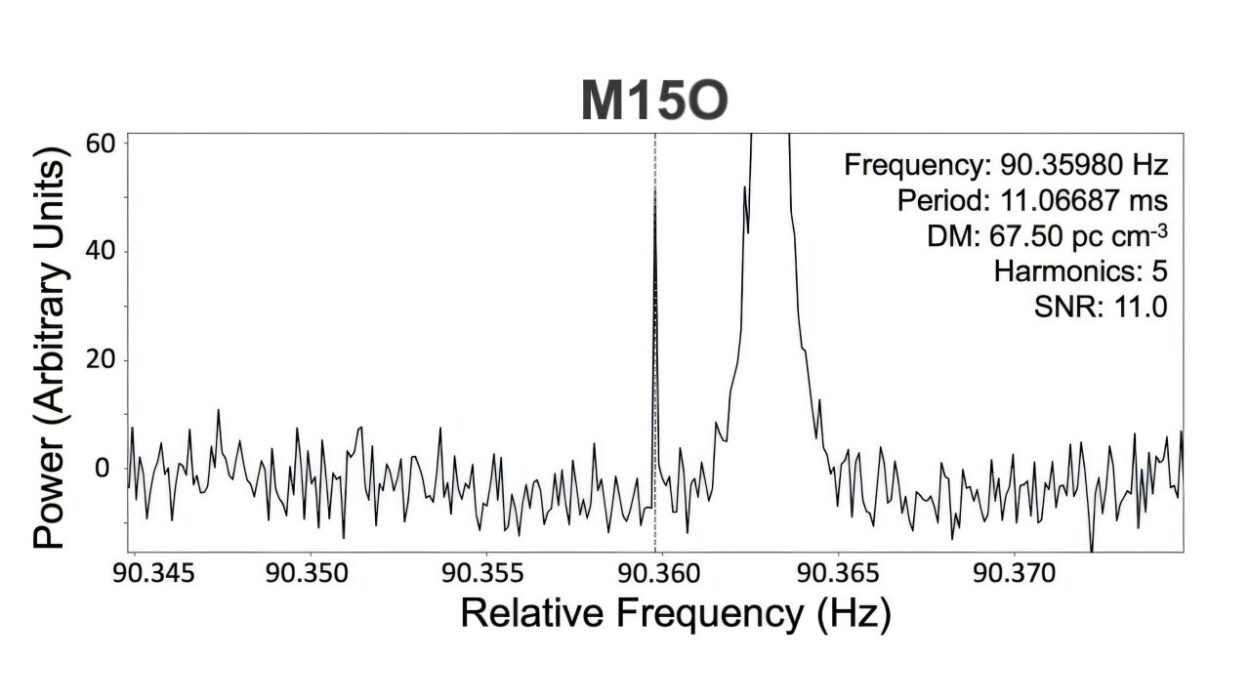

Developed at the Königstuhl Observatory of Heidelberg University and installed at the Calar Alto Observatory, the CARMENES spectrograph can detect radial velocity shifts in starlight with extraordinary precision. It watches how stars wobble—tiny, rhythmic motions that betray the invisible dance of orbiting planets.

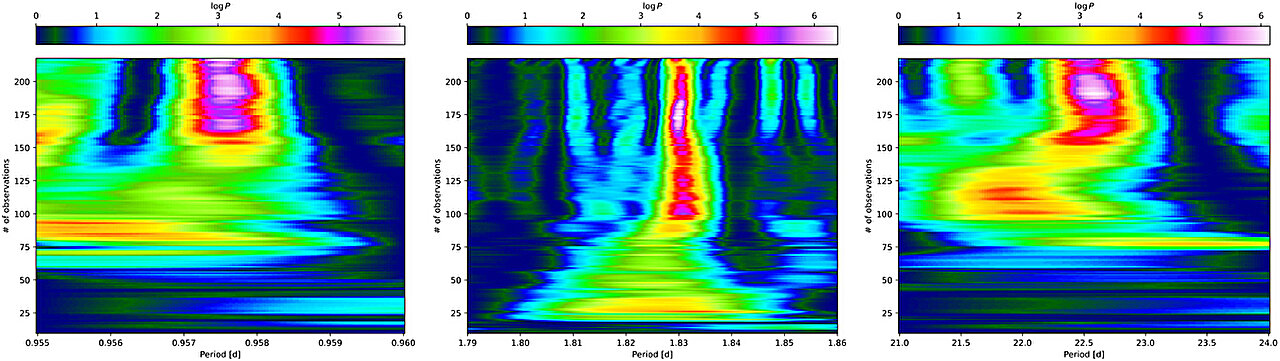

For this study, the team zeroed in on 15 carefully selected M-dwarfs from a much larger catalog of 2,200 stars observed over several years. The result? Four new exoplanets—and new insight into how planetary systems form around these dim stellar neighbors.

Four New Planets, One Surprising Pattern

Among the newly discovered worlds, one is a heavyweight: about 14 times the mass of Earth, circling its host star every 3.3 years. But the real intrigue lies in the other three. Each of them weighs in at just slightly more than Earth, with masses between 1.03 and 1.52 Earth masses. Their orbits are tight—ranging from 1.4 to 5.4 days—but this is common around M-dwarfs, which are cooler and require planets to huddle closer to stay warm.

More importantly, these are the kinds of planets that could be habitable—if found at the right distance from their star.

Statistical modeling based on these findings reveals something striking: low-mass stars with less than 16% of the Sun’s mass tend to have, on average, two small planets each—all under three Earth masses. That’s not just an outlier. It’s a trend.

“It is quite remarkable how often small planets occur around very low-mass stars,” says Dr. Adrian Kaminski, lead author of the study. “This suggests that low-mass stars tend to form smaller planets in close orbits.”

In contrast, large planets like Jupiter or Saturn appear to be rare in these systems, making these stars unlikely places to find gas giants—but increasingly likely places to find rocky worlds like our own.

Chasing the Echoes of Earth

Of the 5,000+ exoplanets discovered so far, none are perfect twins of Earth—matching its size, mass, temperature, and the type of star it orbits. But some come close. And according to Professor Andreas Quirrenbach, director of the Königstuhl Observatory and co-author of the study, the new planets tick several key boxes.

“These new discoveries meet at least the first three criteria,” he explains. “They are small, rocky, and Earth-mass planets. If we find them in the right zone—the so-called habitable zone—they become very interesting candidates.”

That zone—the sweet spot where temperatures could allow water to exist in liquid form—isn’t one-size-fits-all. For M-dwarfs, the habitable zone is much closer to the star, thanks to their lower energy output. But that doesn’t mean these worlds are any less likely to be hospitable. In fact, their long-lived, stable light could be ideal for nurturing life over billions of years.

A New Map of the Cosmic Neighborhood

This research isn’t just about new planets. It’s about reshaping the way we think about where life could exist.

M-dwarfs were once dismissed as poor candidates for habitable worlds. Their flaring, magnetic tantrums and tight habitable zones seemed like a recipe for planetary sterilization. But with each new discovery, that assumption is being challenged.

Now, thanks to CARMENES and the astronomers behind it, we have evidence that these stars are reliable planet factories—and not just any planets, but small, potentially rocky ones that may have the right ingredients for life.

“It’s like realizing you’ve been searching for treasure in all the wrong places,” said one researcher. “The quietest, dimmest stars might be hiding the richest prizes.”

The Search for Life Just Got More Focused

What does this mean for the future of exoplanet exploration? It means the focus may shift away from sun-like stars toward the quiet red glows of M-dwarfs. Instruments like CARMENES are already leading the way, but future missions—like the European Space Agency’s PLATO and NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope—could further investigate these newfound worlds, peering into their atmospheres for signs of water, oxygen, or other markers of habitability.

It also means that the odds may be higher than ever that we are not alone—and that Earth-like worlds may not be the rare cosmic jewels we once believed them to be.

And perhaps, just a few light-years away, orbiting a star you can’t see with the naked eye, a planet much like ours waits quietly, bathed in the soft light of its red sun—spinning, breathing, and maybe even dreaming.

Reference: A. Kaminski et al, The CARMENES search for exoplanets around M dwarfs, Astronomy & Astrophysics (2025). DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/202453381