The history of life on Earth is a tale of epic migrations, evolutionary leaps, and surprising origins. A recent discovery in Spain has added an astonishing chapter to this story, reshaping our understanding of one of the most awe-inspiring predators to ever walk the planet. Long before Spinosaurus prowled the rivers of North Africa, its ancestors may have roamed the landscapes of Europe. This revelation comes from the careful study of a predatory dinosaur named Camarillasaurus cirugedae, whose fossil remains are rewriting the evolutionary map of giant bipedal dinosaurs.

From Tyrannosaurus to Spinosaurus: Giants of the Cretaceous

When most people think of terrifying predatory dinosaurs, the name Tyrannosaurus often comes to mind. Its powerful jaws, massive skull, and upright bipedal posture have made it a symbol of prehistoric ferocity. Yet, in terms of sheer size, Tyrannosaurus was not alone at the top of the food chain. The spinosaurids, a group of giant predatory dinosaurs, claimed a different kind of supremacy. Spinosaurus, the most famous of this group, lived in Africa during the early Late Cretaceous period, approximately 95 million years ago, and could reach staggering lengths of up to 18 meters. It was a predator built to dominate its environment, with adaptations that suggest it hunted both on land and in water.

Until recently, scientists believed that these colossal predators were a purely African phenomenon. But the fossils of Camarillasaurus cirugedae, unearthed in the province of Teruel in central Spain, are telling a very different story.

A Dinosaur Misunderstood: The Early History of Camarillasaurus

The first fossils of Camarillasaurus cirugedae were discovered more than a decade ago, yet their significance was poorly understood. Initially, the dinosaur was classified as a ceratosaur, a smaller and relatively obscure group of predatory dinosaurs in Europe. This classification seemed odd, as ceratosaurs were rare in the Lower Cretaceous of Spain, and some experts considered the find to be “outside of space and time,” hinting at an anomaly in the fossil record.

The early classification was based on a few fragmentary remains. Without more complete evidence, it was difficult to determine the true lineage of this predator. Its story might have remained a minor footnote in paleontological records—until a new excavation campaign brought more of its bones to light.

New Discoveries: Rewriting the Dinosaur Family Tree

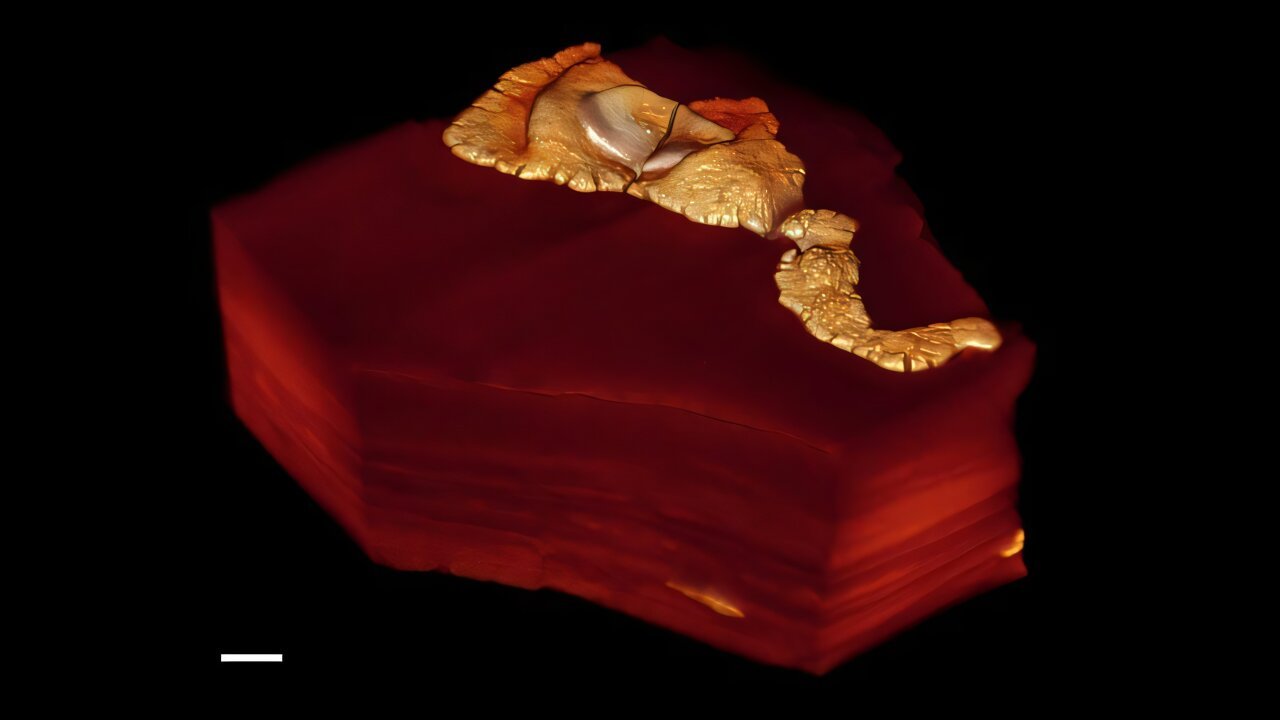

Under the direction of Oliver Rauhut, a leading paleontologist at the Bavarian State Collection of Paleontology and Geology, an international team returned to the original fossil site. Collaborating with researchers from the University of Zaragoza, the team uncovered a wealth of new material: fragments of the jaw, vertebrae from the tail, teeth, a thigh bone, and even a claw from the foot. These discoveries provided a much clearer picture of the animal’s anatomy.

The jawbone fragments, in particular, revealed striking similarities with African spinosaurs, suggesting a close evolutionary relationship. Teeth and vertebral structures further supported this connection. With these new pieces of evidence, paleontologists were able to reclassify Camarillasaurus as a member of the spinosaurid lineage—a revelation that challenges long-standing assumptions about the origin of these gigantic predators.

Europe as the Birthplace of Giant Spinosaurs

Rauhut’s team went further, conducting detailed phylogenetic analyses that traced the evolutionary lineage of spinosaurs. Their results suggest that Camarillasaurus cirugedae was not an isolated anomaly but part of a broader group of Iberian spinosaurs. These European relatives appear to have given rise to the later, massive African spinosaurs, indicating that the giants of North Africa may have originated in Europe.

This finding shifts the narrative of dinosaur evolution. Rather than evolving in Africa independently, the spinosaurids likely began in Europe, gradually spreading to other continents as environmental conditions and land connections allowed. The Iberian Peninsula, rich in spinosaurs mostly represented by teeth, emerges as a key region in understanding the early evolution of these predators.

Hunting Grounds: Terrestrial Predators of the Lower Cretaceous

The fossil record suggests that European spinosaurs, including Camarillasaurus, lived primarily in terrestrial environments. Most of their remains are found in continental deposits, indicating that these dinosaurs were land-based hunters. In contrast, the later North African Spinosaurus is thought to have been semi-aquatic, adapted to catching fish in rivers and lakes. While no evidence yet supports aquatic habits for Camarillasaurus, its robust limbs, claws, and teeth paint the picture of a predator perfectly adapted to stalking prey on land.

This transition—from terrestrial hunters in Europe to semi-aquatic giants in Africa—illustrates the remarkable flexibility and adaptability of spinosaurs. It underscores how environmental pressures can shape anatomy, behavior, and even the habitats of apex predators over millions of years.

A Global Perspective on Dinosaur Evolution

The story of Camarillasaurus cirugedae is more than a tale of a single dinosaur species. It is a window into the broader patterns of dinosaur evolution, migration, and adaptation. By linking European and African spinosaurs, scientists are uncovering how species evolved across continents, responding to shifting climates, changing landscapes, and new ecological opportunities.

These findings also highlight the importance of revisiting and reexamining previously discovered fossils. In this case, bones that were once thought to belong to a minor ceratosaur have now rewritten our understanding of the spinosaurid lineage. Fossil discoveries are rarely static; they are dynamic stories waiting to be retold as new evidence emerges.

The Emotional Impact of Discovery

Beyond the scientific significance, there is an emotional resonance in uncovering the roots of giant predators. To imagine Camarillasaurus cirugedae stalking the plains of Cretaceous Spain, a powerful predator moving through dense vegetation, evokes awe and wonder. It connects us to a world long gone, a time when enormous creatures dominated the land, shaping ecosystems and leaving traces that would endure for millions of years.

Every fossil tells a story not just of biology, but of survival, adaptation, and the relentless passage of time. The discoveries in Teruel remind us that the Earth’s history is richer and more interconnected than we often realize, with Europe playing an unexpected role in the origin of some of the planet’s most formidable predators.

Conclusion: Rewriting the Past, Inspiring the Future

The research on Camarillasaurus cirugedae demonstrates how science continually evolves, reshaping our understanding of the past. From a misunderstood ceratosaur to a key ancestor of African spinosaurs, this dinosaur has revealed new insights into evolution, migration, and ecological adaptation. Europe, once considered a minor player in the story of giant predatory dinosaurs, now appears to be their ancestral cradle.

This discovery not only enriches our knowledge of the Cretaceous world but also inspires future research, urging paleontologists to explore overlooked regions, revisit old fossils, and seek the untold stories hidden in stone. The past is not fixed; it is a living puzzle, and each fossil is a piece that brings the story of life on Earth into sharper focus.

The saga of Camarillasaurus cirugedae reminds us that even millions of years after its extinction, a dinosaur can still ignite curiosity, spark imagination, and reveal the extraordinary connections that bind our planet’s history together.

More information: Oliver W.M. Rauhut et al, Revision of the theropod dinosaur Camarillasaurus cirugedae from the Early Cretaceous (Barremian) of Teruel province, Spain, Palaeontologia Electronica (2025). DOI: 10.26879/1543. palaeo-electronica.org/content … us-theropod-dinosaur