Soy is one of the most controversial foods in modern nutrition, especially when it comes to women’s health. Depending on who you ask, soy is either a plant-based miracle brimming with healing properties or a dietary villain that wreaks havoc on your hormones. The truth, as it often is with food and health, is far more nuanced. For decades, scientists have studied soy for its effects on everything from breast cancer risk to menopause relief, fertility, bone health, and heart disease. Yet even with hundreds of studies behind us, the myths and fears still swirl.

To understand soy’s impact on women’s bodies, we need to dive deeper into the science, bust the myths, and clarify the facts. Because whether you’re sipping soy milk, eating tofu, or avoiding edamame like the plague, the conversation around soy deserves far more clarity—and a lot less fear-mongering.

What Exactly Is Soy and Why Does It Matter?

Soybeans are legumes native to East Asia, where they have been a dietary staple for thousands of years. In countries like Japan, China, and Korea, soy appears in many forms—fermented (as in miso and tempeh), fresh (like edamame), or processed (tofu, soy sauce, and soy milk). In the West, soy’s rise to popularity came much later, largely as a meat and dairy alternative in plant-based diets.

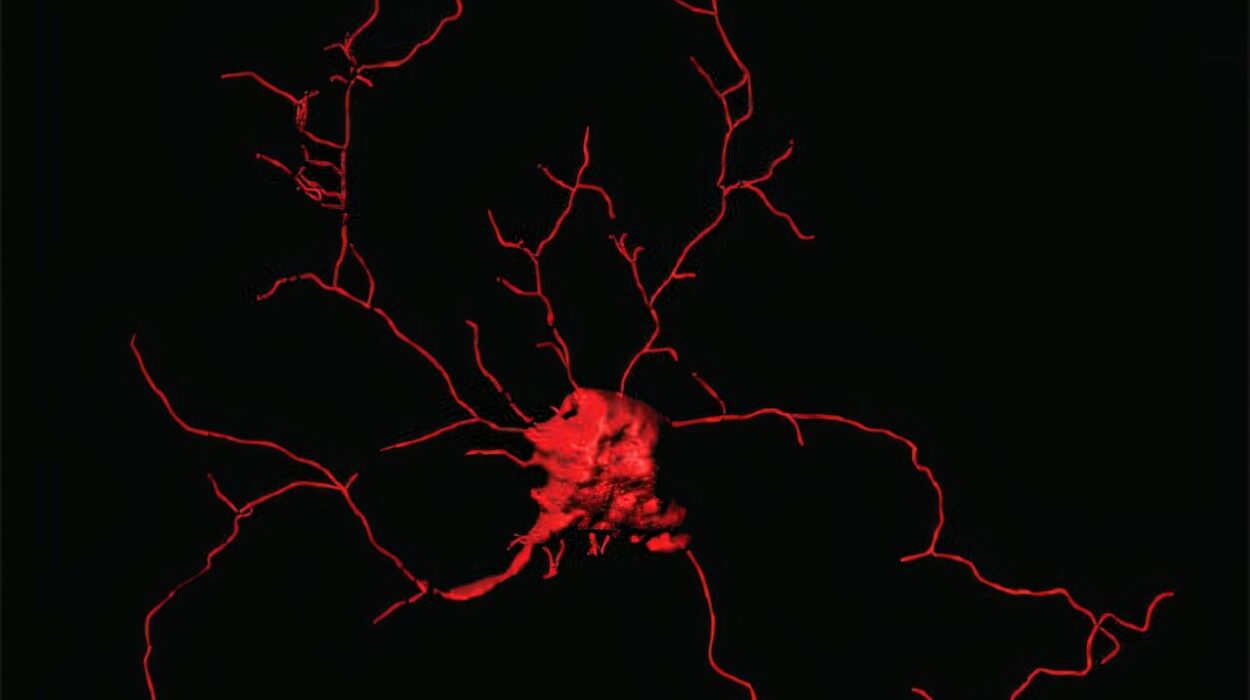

What makes soy unique, and controversial, is its rich content of isoflavones—a type of plant compound known as phytoestrogens. These are not identical to the estrogen produced in human bodies, but they can bind to estrogen receptors and mimic some of estrogen’s effects. For women, this is where the concern begins—and where much of the misunderstanding lies.

Because soy contains these naturally occurring compounds that can behave like weak estrogens, many worry it could interfere with hormonal balance. Would it fuel estrogen-dependent cancers like breast cancer? Could it affect fertility, puberty, or menopause? Would it soften bones or strengthen them? Soy seems to straddle the line between nourishing food and biological wildcard.

To unpack the truth, we need to explore how soy interacts with the body—especially the uniquely complex hormonal system of women.

Phytoestrogens: The Good, the Bad, and the Misunderstood

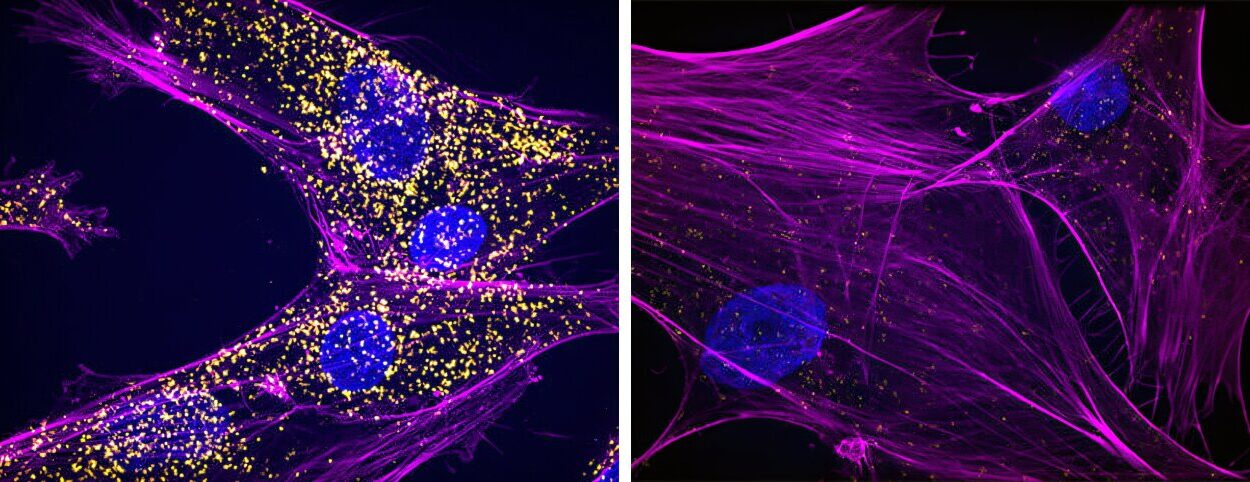

Let’s talk about phytoestrogens. These plant-derived compounds are structurally similar to estradiol, the main form of estrogen in women of reproductive age. But they are not hormones. While they can bind to estrogen receptors, they do so far more weakly than human estrogen. And interestingly, they don’t always act the same way. Depending on the tissue in the body, and the levels of estrogen already present, isoflavones can either mimic or block estrogen’s effects.

This dual behavior is one reason soy’s effects vary so much from person to person. In premenopausal women, who already have high levels of circulating estrogen, soy’s weaker isoflavones may compete with natural estrogen and have an anti-estrogenic effect. In postmenopausal women, who have low estrogen levels, soy’s isoflavones may offer a beneficial boost, mimicking the hormone in ways that can protect against symptoms like hot flashes and bone loss.

This adaptability might explain why in countries with high soy consumption, rates of certain hormone-related diseases, such as breast cancer, osteoporosis, and menopausal symptoms, tend to be lower. But it’s also what makes studying soy so difficult—because its impact depends heavily on a woman’s age, hormonal status, gut microbiome, and even genetics.

Soy and Breast Cancer: Fuel or Fighter?

One of the most persistent fears about soy centers on breast cancer. Because many breast cancers are estrogen-receptor-positive, it’s natural to question whether consuming a food that contains estrogen-like compounds is wise.

But the evidence has consistently painted a reassuring picture. Dozens of studies, especially those following women in Asian populations, have found a reduced risk of breast cancer among women who consume more soy. In fact, women who eat soy regularly throughout their lives—particularly beginning in adolescence—tend to have lower rates of breast cancer later on. This protective effect appears most strongly in whole soy foods like tofu, tempeh, and soy milk—not in ultra-processed soy additives or supplements.

In women who have already been diagnosed with breast cancer, soy was once thought to be risky. But that narrative has shifted. Multiple clinical studies now show that moderate soy consumption does not increase recurrence or mortality risk—and may even improve outcomes. The American Cancer Society and the American Institute for Cancer Research both state that moderate soy consumption is safe for breast cancer survivors, especially when it comes from whole foods.

In other words, the concern that soy acts like estrogen in the body and fuels breast cancer doesn’t hold up to scrutiny. If anything, soy’s weak phytoestrogens may block stronger natural estrogens from binding to receptors, creating a net protective effect. And soy isoflavones also have anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties, which further enhance their health potential.

Soy and Menopause: A Plant-Based Hormonal Ally

Menopause is one of the most transformative chapters in a woman’s life—and one of the most hormonally complex. As estrogen levels drop, many women experience hot flashes, night sweats, mood swings, and vaginal dryness. Hormone Replacement Therapy (HRT) used to be the go-to treatment, but concerns about side effects have made many women wary. Enter soy.

Because of its phytoestrogens, soy has been studied extensively as a natural alternative to hormone therapy. The results? Promising, though not a miracle. Several meta-analyses and randomized controlled trials have shown that soy isoflavones can modestly reduce the frequency and severity of hot flashes, especially when consumed consistently over several months.

But it’s not just about symptoms. Estrogen decline during menopause can also increase the risk of osteoporosis and heart disease. Soy may help here too. Its isoflavones have been shown to improve bone mineral density, especially in the spine, and support vascular health by improving endothelial function and lowering LDL (bad) cholesterol.

Not all women benefit equally. Genetics and gut bacteria determine how efficiently a woman can convert soy’s isoflavones into equol, a metabolite that seems to amplify soy’s hormonal effects. About 30–50% of people are “equol producers,” and these individuals tend to derive more benefit from soy. But even for non-producers, the advantages are real—especially when soy is part of an overall healthy, plant-rich diet.

Fertility, Periods, and Hormonal Cycles

A common concern among younger women is whether soy might disrupt the menstrual cycle or interfere with fertility. After all, if it affects estrogen receptors, could it throw things off balance?

The research says: probably not. In fact, studies have generally found that moderate soy intake has no significant negative impact on ovulation, menstrual cycle length, or hormone levels in healthy premenopausal women. Some evidence even suggests that soy could be beneficial for reproductive health. In women undergoing fertility treatments like IVF, soy isoflavones have been associated with better embryo implantation and pregnancy rates.

There’s also interest in soy’s effects on Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS), a condition marked by hormonal imbalance, insulin resistance, and irregular periods. Preliminary studies suggest that soy may improve metabolic markers and help regulate cycles in women with PCOS, possibly due to its anti-inflammatory and insulin-sensitizing properties.

Of course, no food is a panacea. Women trying to conceive should focus on a balanced, nutrient-dense diet that supports hormonal and metabolic health. But soy, in moderation, does not appear to be the reproductive disruptor some fear it to be.

Thyroid Function: Separating Fact from Fiction

Another area of controversy is the thyroid. Soy has long been accused of interfering with thyroid function, especially in people with hypothyroidism. The concern stems from early studies showing that isoflavones can inhibit thyroid peroxidase, an enzyme involved in the production of thyroid hormones.

But the key detail is often missed: these effects occur primarily when iodine intake is low. Iodine is a crucial nutrient for thyroid health, and when iodine levels are adequate, the impact of soy on the thyroid appears to be minimal. Large population studies, including those in countries with high soy consumption, have not found increased rates of thyroid dysfunction.

For women with well-managed hypothyroidism who are getting enough iodine (either from food or supplements), moderate soy intake is generally considered safe. The one caveat is timing: because soy may slightly interfere with the absorption of thyroid medication, it’s best to take your meds on an empty stomach and wait a few hours before consuming soy products.

Heart Health and Cholesterol Benefits

Cardiovascular disease remains the leading cause of death among women worldwide, and lifestyle choices play a huge role in prevention. Soy shines particularly bright in this area.

Numerous clinical studies have shown that soy protein can lower LDL cholesterol by as much as 4–6%, particularly when it replaces animal protein in the diet. That may not seem dramatic, but it’s significant on a population level. The FDA once allowed food companies to make heart health claims about soy, and although the language has since been softened, the underlying data remains strong.

Soy is also rich in unsaturated fats, fiber, and plant sterols, all of which support heart health. It can help reduce blood pressure, improve vascular elasticity, and lower systemic inflammation—all important for keeping your heart ticking smoothly.

And for women entering or going through menopause, this is especially important. Estrogen has a protective effect on the cardiovascular system, and as it declines, heart disease risk rises. Soy, with its gentle estrogen-like effects and cholesterol-lowering properties, may offer a protective bridge.

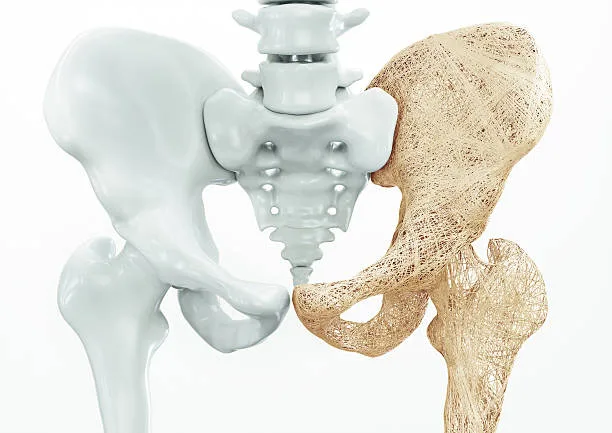

Bone Health and Aging Gracefully

Estrogen doesn’t just affect moods, periods, and breasts—it also helps maintain strong bones. As women age and estrogen declines, the risk of osteoporosis increases sharply. Calcium and vitamin D are key nutrients, but soy may play a valuable supporting role.

Studies have found that soy isoflavones can help maintain or even improve bone mineral density, particularly in postmenopausal women. The effects are not as potent as pharmaceutical bone drugs, but they are meaningful—especially when soy is part of a balanced, whole-food diet.

Tempeh, tofu, and fortified soy milk also provide calcium and magnesium, two minerals essential for bone strength. And because soy is plant-based, it lacks the saturated fat found in some animal-based calcium sources.

Not All Soy Is Created Equal

Here’s where things get complicated: not all soy products are the same. Whole, minimally processed soy foods—like edamame, tofu, miso, tempeh, and soy milk—are rich in isoflavones, fiber, and nutrients. They offer all the benefits we’ve explored.

But highly processed soy additives—like soy protein isolate in protein bars, snacks, and fast food—are another story. These products are often stripped of fiber, over-processed, and served up alongside added sugars, artificial flavors, and unhealthy fats. While these ingredients may still contain isoflavones, their overall impact on health is murkier.

To reap soy’s benefits without falling into the processed food trap, focus on whole soy sources. If your soy comes wrapped in plastic, buried in a protein bar, or smothered in chemicals, it’s probably not the kind of soy that nourishes your hormones or protects your heart.

So, Should Women Eat Soy? The Final Verdict

The bottom line is simple: moderate consumption of whole soy foods is not only safe but potentially beneficial for women of all ages. From puberty to postmenopause, soy interacts with your body in dynamic, often protective ways. It may reduce your risk of breast cancer, support bone and heart health, ease menopausal symptoms, and offer a plant-based protein source that’s gentle on the planet.

The fears around soy are largely rooted in outdated studies, misinterpretations, or lab tests that don’t translate to human biology. When placed in the context of a diverse, whole-food diet, soy emerges not as a hormonal threat but as a powerful ally.

Science is never finished, and research on soy continues. But what we know today is enough to shift the narrative. Women don’t need to fear soy. They need to understand it—and perhaps, embrace it.

If you’d like this article turned into a printable or shareable PDF, blog post layout, or shortened version for social media, let me know!