Every day, we make thousands of decisions—some trivial, like what to eat for breakfast, and others profound, shaping the course of our lives. Yet, beneath the surface of conscious awareness, the brain is a bustling hub of complex processes that drive these choices. Decision-making is far more than a simple matter of willpower or rational thought. It is a dynamic interplay of emotions, memories, predictions, and computations, orchestrated by intricate neural networks.

Understanding the neuroscience behind decision-making is not just a scientific endeavor; it is a journey into what makes us human. It reveals why we sometimes make choices that defy logic, why habits can be so hard to break, and how we might improve our ability to choose wisely. This article explores the remarkable machinery of the brain that underpins decision-making and offers insights that can help guide us toward better decisions in everyday life.

The Architecture of Choice: Brain Regions Involved

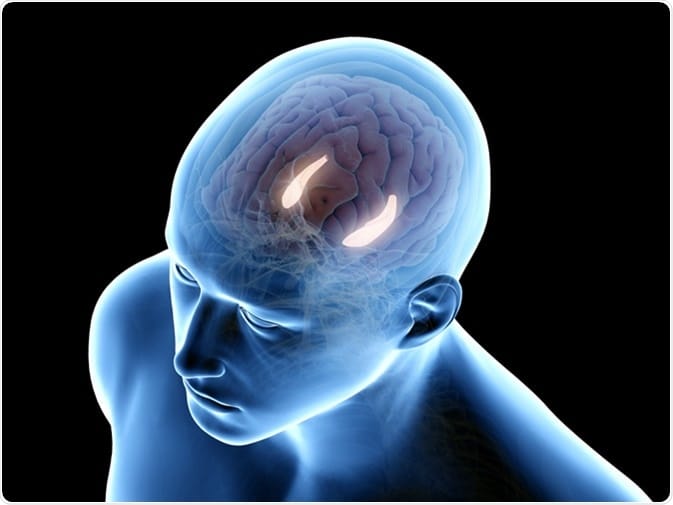

At the heart of decision-making lies a complex symphony of brain regions, each contributing unique functions. The prefrontal cortex, often dubbed the brain’s CEO, is central in evaluating options, weighing consequences, and exerting self-control. This region matures late in human development, which partly explains why children and adolescents often struggle with impulsivity.

Beneath the cortex, deeper structures like the basal ganglia and the limbic system play pivotal roles. The basal ganglia help in habit formation and procedural learning, enabling us to make rapid decisions based on experience. The limbic system, particularly the amygdala, is the emotional center, assigning value and urgency to choices by processing feelings like fear, pleasure, and reward.

The interplay between these regions can be thought of as a dialogue between reason and emotion. While the prefrontal cortex seeks to apply logic and long-term thinking, the limbic system injects passion and immediacy. Neuroscientific research has shown that these two often compete and cooperate in subtle ways, influencing whether a choice is impulsive or deliberate.

The Role of Neurotransmitters: Chemistry of Decision

Underlying the brain’s decision networks are chemical messengers called neurotransmitters, which modulate neuronal communication. Dopamine, perhaps the most famous among these, plays a crucial role in motivation, reward, and learning from outcomes. When you anticipate a reward, dopamine neurons fire, creating a sense of excitement and driving you toward that goal.

However, dopamine’s influence is not simply about pleasure. It acts as a teaching signal, helping the brain to update expectations based on feedback—a process known as reinforcement learning. This mechanism allows us to learn from past mistakes and successes, refining our future decisions.

Serotonin, another key neurotransmitter, has a more complex relationship with decision-making. It is implicated in mood regulation, patience, and impulse control. Lower levels of serotonin are linked to impulsive behavior and difficulty delaying gratification, suggesting that it acts as a brake on hasty choices.

The balance between these and other neurotransmitters shapes the brain’s decision-making landscape, influencing how we assess risks, rewards, and consequences.

Emotions: The Invisible Hand in Choice

For a long time, emotions were regarded as the enemies of rational decision-making. The ideal of humans as purely logical agents persisted, with feelings seen as irrational interruptions. Neuroscience, however, has upended this notion, revealing that emotions are integral to effective choice.

The somatic marker hypothesis, proposed by neuroscientist Antonio Damasio, argues that emotional signals guide decision-making by attaching bodily feelings to potential outcomes. These “markers” help us avoid harmful situations and gravitate toward beneficial ones, even before conscious reasoning kicks in.

Consider the gut feeling you experience when making a tough decision—a sense of unease or excitement. This embodied emotion is not mere superstition; it reflects a rapid neural process where the brain integrates emotional memories and bodily states to bias choices.

Indeed, damage to brain areas involved in emotional processing, like the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, leads to impaired decision-making despite intact logical reasoning. Patients with such injuries may understand risks in the abstract but fail to avoid decisions that have negative real-world consequences.

Cognitive Biases: When the Brain Tricks Itself

Despite its sophistication, the brain is prone to systematic errors known as cognitive biases. These biases arise from shortcuts—heuristics—that the brain uses to process information efficiently but imperfectly.

One well-known bias is confirmation bias, where individuals favor information that confirms their pre-existing beliefs, ignoring contradictory evidence. This tendency can trap decision-makers in echo chambers and poor judgments.

Loss aversion, another powerful bias, means that people feel the pain of losing something more intensely than the pleasure of gaining an equivalent amount. This can cause risk-averse behavior that may prevent beneficial opportunities.

Understanding these biases is crucial because they reveal the hidden traps within our cognitive architecture. Neuroscience has linked many biases to specific brain activities—for example, the amygdala’s heightened response to potential losses compared to gains.

By recognizing these mental shortcuts, we can develop strategies to mitigate their influence, such as seeking diverse perspectives and deliberately slowing down decision processes.

The Influence of Stress and Fatigue

Decisions are rarely made in ideal conditions. Stress and fatigue can profoundly alter the brain’s functioning, often tipping the balance toward impulsivity and poor choices.

Under stress, the brain’s release of cortisol affects the prefrontal cortex, impairing working memory and executive function. At the same time, stress heightens activity in the amygdala, priming the individual for quick, survival-oriented decisions but at the expense of thoughtful deliberation.

Fatigue similarly diminishes the brain’s capacity for self-control and complex reasoning. When tired, people are more likely to rely on habits or immediate rewards rather than long-term goals.

Recognizing the impact of stress and fatigue on decision-making underscores the importance of managing these states—through rest, mindfulness, or supportive environments—to maintain cognitive clarity.

Social Context: How Others Shape Our Choices

Humans are inherently social beings, and our decisions often occur in a social context that profoundly influences outcomes. Neuroscience has uncovered how brain regions involved in empathy, theory of mind, and social reward shape decision-making.

Mirror neurons, for example, allow us to simulate and understand others’ actions and intentions, facilitating cooperation and trust. The medial prefrontal cortex activates when considering how others perceive us, driving conformity or resistance depending on circumstances.

Social rewards—such as approval or status—activate dopamine pathways, motivating behaviors aligned with group norms. Conversely, social rejection activates brain areas associated with physical pain, making the fear of exclusion a potent driver of choice.

Understanding the neural basis of social influence can help us navigate peer pressure and group dynamics more effectively, fostering decisions that balance individual goals with social harmony.

The Dual-Process Model: Intuition versus Reason

A major framework in decision neuroscience is the dual-process model, which posits two systems guiding our choices. System 1 is fast, automatic, and emotional; it operates with little conscious effort and relies on heuristics. System 2 is slow, deliberate, and logical, engaging when complex reasoning is needed.

Neuroscience supports this division by showing distinct neural pathways: System 1 depends heavily on the limbic system, while System 2 recruits the prefrontal cortex.

Both systems have strengths and weaknesses. System 1 enables quick responses vital in emergencies but can lead to biases. System 2 allows for thorough analysis but is effortful and prone to fatigue.

Effective decision-making involves knowing when to trust intuition and when to engage rational deliberation. Cultivating mindfulness and awareness can improve this balance.

Neuroplasticity and Decision-Making: Changing How We Choose

One of the most hopeful findings in neuroscience is the brain’s plasticity—its ability to change structurally and functionally in response to experience.

Decision-making skills can be improved through training and practice. Techniques like cognitive behavioral therapy help rewire maladaptive thought patterns, reducing impulsivity and enhancing self-control.

Meditation and mindfulness practices have been shown to increase prefrontal cortex thickness and improve emotional regulation, leading to better decisions.

Even habits, once deeply ingrained in the basal ganglia, can be altered through intentional effort, creating new neural pathways that favor healthier choices.

This malleability means that better decision-making is not fixed by biology but can be cultivated.

The Future of Decision Neuroscience: Technology and Ethics

As neuroscience advances, emerging technologies like brain imaging, neurofeedback, and even brain-computer interfaces offer new ways to understand and influence decision-making.

Researchers are exploring how real-time monitoring of brain activity can identify moments of cognitive bias or emotional overwhelm, allowing interventions to improve choices.

However, these developments raise ethical questions. If technology can manipulate decisions, where is the line between assistance and control? How do we preserve autonomy in a world of neuro-enhancement?

These questions underscore the importance of integrating scientific progress with philosophical and ethical reflection.

Practical Strategies for Better Decisions

While the brain’s inner workings are complex, several principles emerge that can guide us toward better choices.

Slowing down and allowing System 2 reasoning to engage can mitigate impulsive errors. This might mean taking time to reflect before important decisions or consulting others to gain perspective.

Cultivating emotional awareness helps harness the wisdom of feelings without being overwhelmed by them.

Managing stress and ensuring adequate rest preserves the brain’s executive function.

Being mindful of biases encourages openness and critical thinking.

Finally, embracing the brain’s plasticity empowers continuous improvement—decision-making is a skill that can grow.

Conclusion: Embracing the Mystery of Choice

Decision-making is a deeply human act, a dance between biology and experience, emotion and reason. Neuroscience reveals that while our brains are wired with tendencies and limitations, they are also remarkable engines of learning and adaptation.

By understanding the neural roots of our choices, we gain insight not only into how we decide but why. This knowledge is a call to compassion—toward ourselves when we falter and toward others whose choices may differ.

Ultimately, the neuroscience of decision-making is a map of our humanity, offering pathways to wiser choices and richer lives.