Since the very first astronauts broke free from Earth’s gravity, scientists have watched closely as the human body adapts—or fails to adapt—to space. Floating in microgravity may look graceful on television, but inside the body, the story is less poetic. Muscles weaken, bones thin, and even the shape of the heart can change. Yet one of the most puzzling and potentially dangerous effects has only recently begun to be understood: astronauts’ vision fades in space.

In orbit, limbs lengthen slightly and fluids shift toward the head, pressing against the eyes and brain. The consequences can be profound. Astronauts who once had perfect sight have returned home struggling to read road signs or computer screens. Some recover in weeks, others in months, and some live with lingering vision problems for years. In 2017, scientists gave this unsettling condition a name—Spaceflight Associated Neuro-ocular Syndrome (SANS).

NASA data reveals the scale of the issue: about 29% of astronauts on short missions reported vision problems, while that number skyrockets to 60% for longer journeys. For a space program dreaming of Mars, where missions may last years, this is a critical concern.

An Unseen Threat

The eye is a delicate organ, finely balanced between pressure, fluids, and light-sensitive tissues. In space, the absence of gravity disrupts this equilibrium. Fluid that would normally settle in the lower body moves upward, crowding the skull and pressing against the optic nerve. The result: swelling, blurred vision, and structural distortions that can leave lasting scars.

Astronauts are trained for countless emergencies—fires, collisions, equipment failures—but vision loss is a more insidious danger. It creeps up slowly, without alarms, and yet it could compromise a mission as surely as a mechanical failure. After all, how can you land on Mars or repair a spacecraft if your sight is failing?

AI Steps In

To tackle this mystery, researchers at the University of California San Diego joined forces with the Shiley Eye Institute, the Viterbi Family Department of Ophthalmology, and the Halıcıoğlu Data Science Institute. Their mission was bold: to use artificial intelligence to predict which astronauts are most at risk of vision loss before they ever leave Earth.

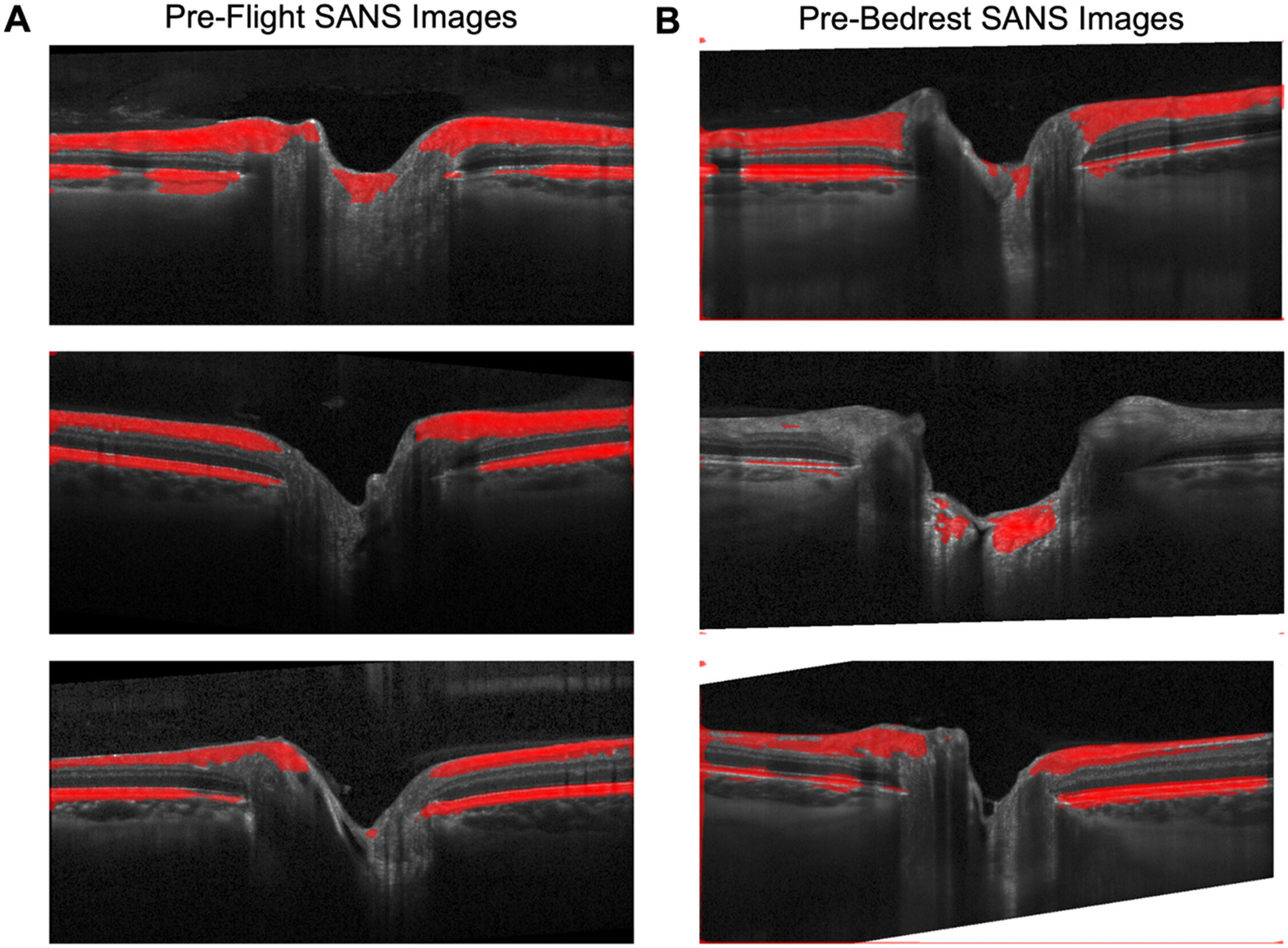

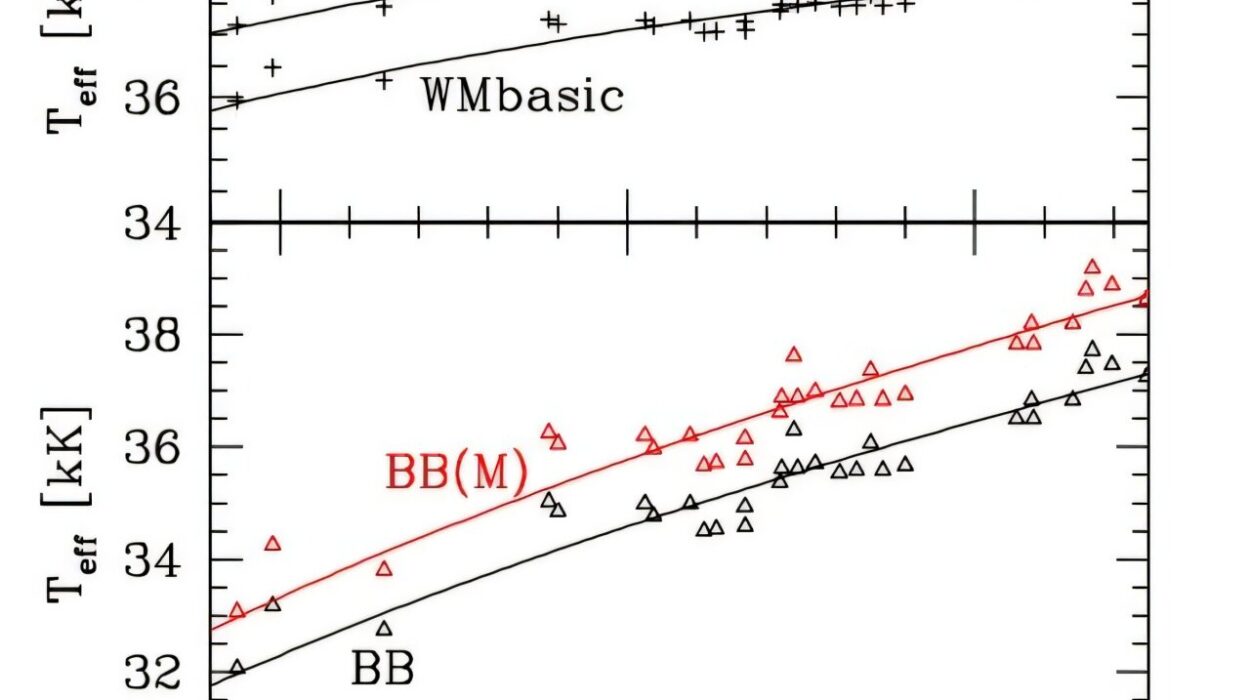

The team fed their algorithms optical coherence tomography (OCT) scans—microscope-like images of the optic nerve—collected before and during space missions. They also used data from Earth-based studies in which volunteers spent weeks in a six-degree downward tilt, a method designed to mimic how microgravity shifts fluids toward the head.

But data was scarce. Only a small number of astronauts have flown in space, and even fewer have had complete medical imaging done. To overcome this, the researchers turned to deep learning techniques. They broke scans into thousands of tiny slices, augmented the data, and used transfer learning so the AI could generalize from limited examples.

Then came the heavy lifting. Training these models required massive computing power, so the team turned to the Expanse supercomputer at the San Diego Supercomputer Center, with allocations provided by the National Science Foundation’s ACCESS program. The result was remarkable: the AI could predict SANS with up to 82% accuracy using only preflight scans.

What the Machines Saw

Artificial intelligence is often described as a black box—powerful, but difficult to interpret. To peer inside, the team used class activation maps, creating heatmaps that reveal where the AI was focusing. Strikingly, the models highlighted eye layers tied to fluid balance and pressure regulation, such as the retinal nerve fiber layer and the retinal pigment epithelium.

This offered more than just prediction; it gave researchers new biological insights. It suggested that SANS is not random but linked to specific structural vulnerabilities in the eye. And if those can be identified before launch, astronauts could receive personalized risk assessments and preventive care.

A Future of Safer Spaceflight

The implications are profound. Imagine a future mission to Mars where crew members undergo preflight scans. AI systems flag those at high risk, and doctors provide targeted countermeasures—perhaps specialized exercise, medication, or even surgical interventions—to protect their eyes. During flight, AI-powered monitoring could track changes in real time, alerting astronauts to intervene before symptoms worsen.

For now, the UC San Diego team stresses that their models are preliminary. The dataset is still small, and much more research is needed before these tools can be trusted in clinical settings. But the foundation is strong. Each discovery brings us closer to ensuring that astronauts not only survive but thrive in deep space.

Earthly Benefits of Space Science

While this research is born of space exploration, its impact may extend far beyond astronauts. Eye diseases on Earth—from glaucoma to macular degeneration—share similarities with SANS. The same AI tools developed to protect astronauts may one day help doctors predict vision loss in millions of patients on Earth, offering earlier diagnoses and more effective treatments.

This is one of the great ironies of space science: in trying to conquer the stars, we often improve life at home. Technologies from MRI machines to GPS began as space-related research. The effort to preserve astronauts’ eyesight may end up safeguarding ours.

A Fragile Vision of the Future

Humanity stands on the edge of a new era. Space agencies and private companies alike are preparing for long journeys beyond Earth—missions to the Moon, Mars, and perhaps further still. But as we dream of these frontiers, we must not forget the fragility of the human body.

Space is not kind to us. It reshapes our muscles, weakens our bones, and threatens our sight. Yet through ingenuity, persistence, and tools like artificial intelligence, we are learning how to fight back.

The story of vision loss in space is not just about risk. It is about resilience. It is a reminder that every step into the cosmos is also a step inward—an exploration of what it means to be human, fragile yet determined, vulnerable yet endlessly curious. And as we look to the stars, AI may help ensure that our eyes are ready to see them.

The study is published in the American Journal of Ophthalmology.