In the dim interior of a breast tumor, where oxygen runs low and acidity rises to levels that would poison most living cells, something remarkable unfolds. Healthy cells fail quickly in such punishing terrain, but cancer cells persist, divide, and adapt with astonishing precision. UCLA scientists have now uncovered part of the reason why. Deep inside these cells operates a molecular machine whose structure and movements have remained largely mysterious—until now. Their new study, published in Nature Communications, reveals the architecture and choreography of a protein that helps cancer cells defy their environment.

The Quiet Guardian of Cellular Balance

At the center of the discovery is NBCn1, a transporter protein embedded in the plasma membrane of breast cancer cells. Though small, its job is immense. NBCn1 helps control internal pH by pulling alkali ions into the cell. Without such chemical balancing, the acidic surroundings of tumor tissue would cripple essential cellular functions. Yet cancer cells not only survive—they flourish.

The UCLA team has now shown, with striking clarity, how NBCn1 performs this role. The transporter moves two sodium ions and one carbonate ion into the cell in a highly efficient motion described as “elevator-like.” Rather than relying on energetically expensive steps, NBCn1 uses subtle structural shifts to pass ions through at extraordinary speed—about 15,000 ions every second. This rapid transport helps breast cancer cells maintain the alkaline interior they need to grow, divide, and resist the stress of their acidic environment.

Tumors accumulate acid because their metabolism runs hot and oxygen supplies dwindle. Under such conditions, many cells buckle under the pressure of chemical imbalance. Cancer cells, however, alter their internal equilibrium through specialized transporters like NBCn1. For years, researchers recognized NBCn1 as a major regulator of cellular pH, but details about its structure and mechanics remained elusive. Understanding those details, the UCLA team believed, could uncover new vulnerabilities in cancer biology.

Seeing the Unseen with Atomic Clarity

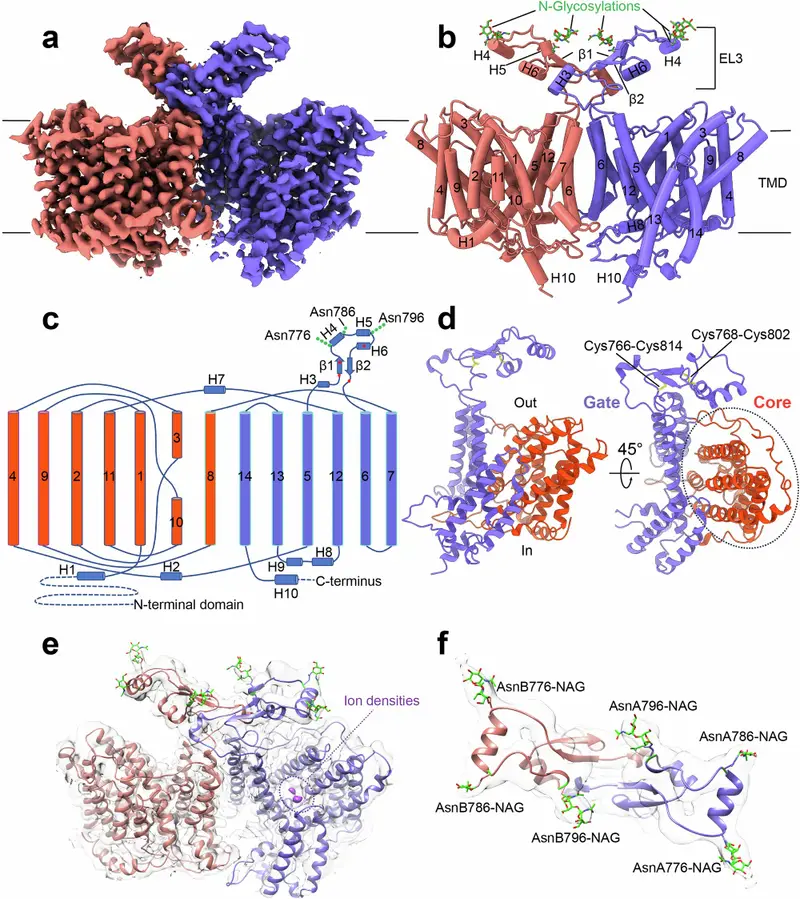

To explore NBCn1’s inner workings, the researchers relied on the precision of cryo-electron microscopy. This technique, which freezes proteins in place and images them at near-atomic resolution, allowed the team to produce the first three-dimensional structure of human NBCn1. What they captured was not just a static snapshot but the framework of a machine built for flexibility and speed.

They paired these images with advanced computational modeling, simulating the way NBCn1 shifts shape to shepherd ions across the membrane. These models revealed how the transporter uses pathways that allow ions to move with minimal resistance. The “elevator-like” mechanism emerged as a key insight: NBCn1 undergoes coordinated structural changes resembling a platform rising and falling, carrying ions from one side of the membrane to the other. Each motion is small, but together they create a system that maximizes efficiency while minimizing energy demand.

These glimpses into the transporter’s dynamic behavior showed precisely how NBCn1 accomplishes its remarkable throughput. They also shed light on how closely the protein’s design is tied to its function—subtle structural features allow ions to enter, pass through, and exit with astonishing speed.

A Blueprint for Future Therapies

By linking structure, energetics, and function, the study moves beyond basic characterization. It establishes a foundation for therapeutic exploration. If cancer cells rely on NBCn1 to survive under acidic stress, then blocking this transporter could disrupt their chemical stability. Such an approach could weaken tumor cells without broadly harming healthy tissue, which does not depend on NBCn1 to the same extent.

“This work advances the field of cancer cell metabolism and membrane transport biology by providing the first atomic-level model of NBCn1, a major regulator of cellular pH,” said Dr. Ira Kurtz, a Distinguished Professor of Medicine, Factor Chair in Molecular Nephrology and a member of the UCLA Brain Research Institute.

For Dr. Kurtz and his colleagues, the significance lies not only in revealing the structure but in uncovering the principle behind its efficiency. “By linking the protein’s structure, ion energetics, and function, the study shows how small molecular motions can generate high transport efficiency. These insights bridge a critical knowledge gap between basic biophysics and cancer therapeutics and lay the groundwork for new strategies that target pH regulation as a vulnerability in tumor cells.” His words capture the study’s core motivation: to illuminate a molecular behavior that could become a targetable weakness.

Why This Discovery Matters

The harsh interior of a tumor has long posed both a challenge and an opportunity in cancer research. Conditions such as low oxygen and high acidity harm healthy cells but favor aggressive cancer behavior. Understanding how tumor cells adapt offers a route to undermining their survival strategies.

This new work reveals one such adaptation with unprecedented clarity. NBCn1 is not merely a supporting player; it is a molecular lifeline that helps breast cancer cells stabilize their pH under duress. By showing exactly how this transporter achieves its exceptional efficiency, the UCLA researchers provide a roadmap for designing molecules that might disrupt its activity. Such therapies could exploit a fundamental weakness in tumor survival mechanisms, potentially increasing the effectiveness of existing treatments or offering new strategies altogether.

The study stands as a reminder that even in the most inhospitable environments, cancer cells rely on intricate molecular architectures to stay alive. By exposing those architectures in detail, scientists inch closer to turning those strengths into vulnerabilities.

More information: Weiguang Wang et al, CryoEM and computational modeling structural insights into the pH regulator NBCn1, Nature Communications (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-64868-z