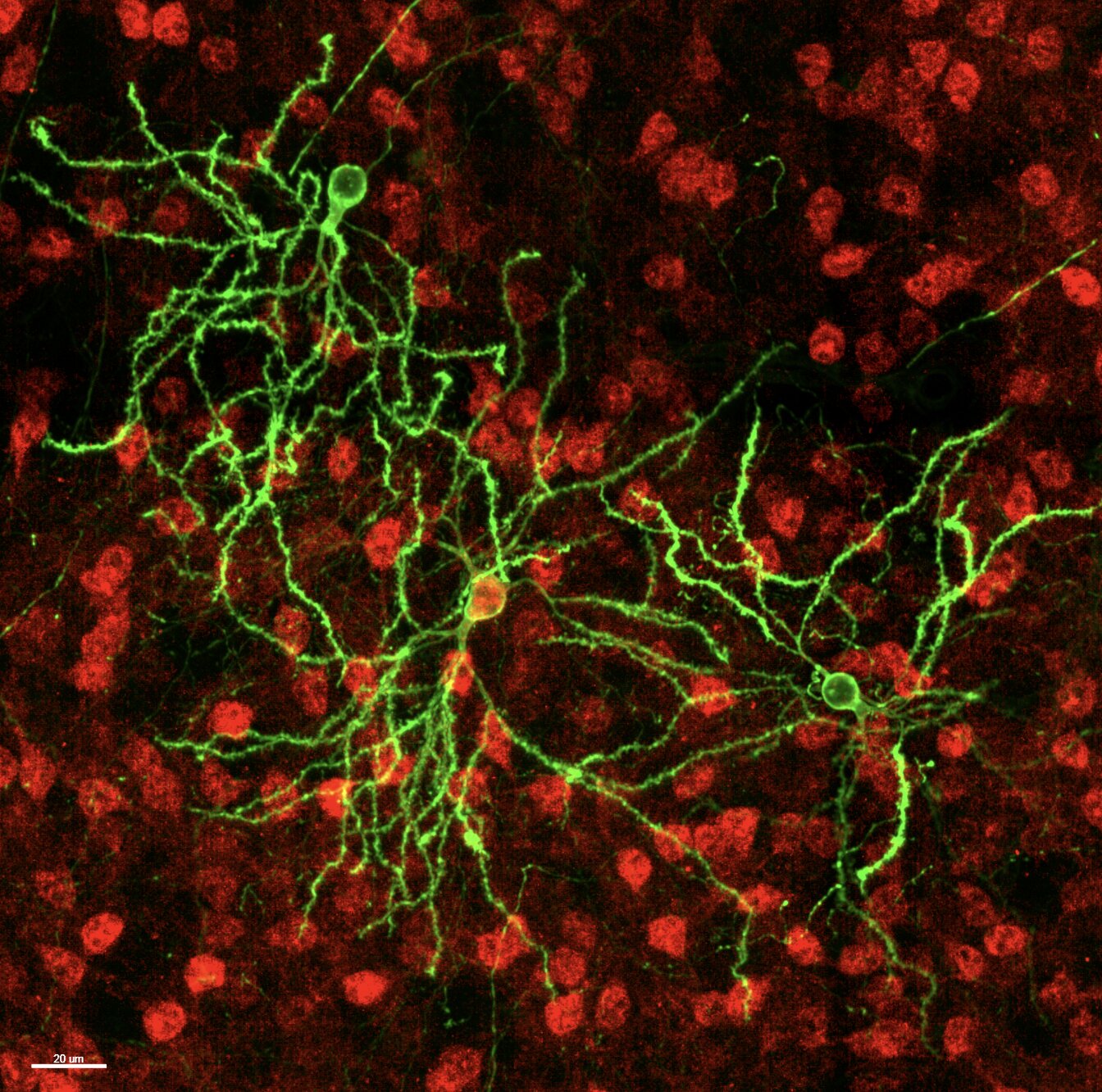

Deep inside the brain, a forest stretches beyond what the eye can see. This forest is not made of trees, but of neurons—tiny cells that branch out like intricate root systems, capturing signals from other cells and carrying whispers of thought, memory, and movement. Understanding the shape of these neurons, particularly their sprawling dendrites, has long been one of neuroscience’s most tantalizing mysteries. The way these branches spread, twist, and connect could hold the key to unlocking how the brain processes information and what goes awry in neurological and psychiatric disorders.

At the University of California, Los Angeles, the X. William Yang Lab has taken bold steps into this forest. Using sophisticated new methods that combine genetic labeling, high-resolution imaging, and computational analysis, the researchers have mapped the dendritic landscapes of thousands of neurons in the mouse brain. The result is a kind of atlas, a glimpse into the hidden geometry of the mind, revealing how different types of neurons may be wired to shape behavior, learning, and disease.

Rediscovering the Wisdom of the Past

“The foundation of modern neuroscience was established by Ramón y Cajal who studied the shape of neurons using Golgi staining over a century ago,” explained Dr. Chang Sin (Chris) Park, first author of the study. “Cajal’s Nobel-prize-winning work demonstrated that a fundamental understanding of the brain requires in-depth knowledge of its basic building block, individual neurons.”

Cajal’s work, painstaking and meticulous, laid the groundwork for every modern brain map. Yet despite a century of technological advancement, mapping neurons remains a staggering challenge. While the human brain contains roughly 86 billion neurons, only about 200,000 have ever been imaged and digitally reconstructed for their shape. Even in mice, with their comparatively tiny brains, morphological studies have been limited to small samples of neurons, often analyzed in two-dimensional slices rather than within thick, intact tissue.

“Despite the vast number of neurons in the human brain and the mouse brain, only about 200k neurons have ever been imaged and digitally reconstructed for their shape,” said Dr. X. William Yang. To overcome this challenge, his team obtained three NIH BRAIN Initiative grants and set out to develop genetic and computational tools capable of mapping individual neurons at unprecedented scale and resolution.

Lighting Up the Brain

The breakthrough began with MORF mice, a genetically engineered model designed to label neurons sparsely but brightly. “MORF mice capture at high resolution the shape of single neurons of a genetic type by simply breeding the mice,” Yang and Park explained. This method is far less labor-intensive than traditional approaches that rely on dyes or viral injections, allowing researchers to visualize the complex branching of individual neurons with unprecedented clarity.

Using this model, the team developed a new systems biology approach they call dendritome mapping. This technique allows them to systematically chart the dendritic shapes of thousands of neurons, providing a detailed portrait of how signals might flow through the brain. Their initial focus was on two genetically distinct types of striatal neurons, D1- and D2-type medium spiny neurons, which are central to voluntary movement, habit formation, and higher cognitive functions like decision-making.

A Forest in Three Dimensions

To understand the true form of these neurons, the researchers needed more than 2D slices. They cleared thick sections of mouse brain tissue using iDISCO, which allows light to penetrate deep into the sample, and imaged the neurons in three dimensions. Computational tools stitched these images into a coherent map, registering each neuron to a reference atlas known as CCFv3.

“Together with our colleagues, we developed an integrated computational pipeline with a novel algorithm to register the thick brain sections to the 3D mouse brain reference atlas, a streamlined digital neuronal reconstruction process, and comprehensive statistical analysis of neuronal shape with 31 morphometric features per neuron,” Park explained.

But they didn’t stop there. To study subtle variations in dendritic architecture, they divided the striatum into thousands of tiny cubic boxes, analyzing the neurons within each box for shared morphometric patterns. This voxel-based approach allowed them to detect clusters of neurons with strikingly similar dendritic features, forming what they called “morphological territories.”

Revealing the Hidden Patterns

The results were surprising. While D1- and D2-type neurons were largely similar, D1 neurons were slightly larger and more complex in certain subregions. More importantly, the box analysis revealed that neurons organize into dendritic modules, clusters of cells sharing similar shapes but differing sharply from neighboring modules.

“Using the ‘box analysis, we found that the striatal MSNs are organized into groups of MSNs with shared ‘dendritic modules,’ which have strikingly similar dendritic features within a module and quite divergent features across modules,” Yang and Park explained.

These modules correspond to regions receiving different inputs from the cortex, suggesting that variations in dendritic architecture may reflect the specific circuits each neuron participates in. The study also revealed how aging and disease affect these structures. Aging uniformly shrinks dendrites, a phenomenon known as dendritic atrophy, while a Huntington’s disease model produced more subtle, selective deficits in D1- and D2-neurons.

Mapping the Future

The implications of this research extend far beyond the mouse brain. By providing the first striatum-wide dendritic atlas of D1- and D2-MSNs, the study lays a foundation for future investigations into how specific neuronal morphologies relate to disease. Yang, Park, and their team are now expanding the MORF toolkit to include genetic perturbations, allowing them to probe how genes influence dendritic shape and connectivity. They are also exploring applications in other neurodegenerative disorders, including Alzheimer’s disease.

“Our work provides the first striatum-wide D1- and D2-MSN dendritic morphological atlas in the adult mouse brain,” the authors said. “This database can be used as a reference for future studies of the development, biology, and pathology of these important neuronal types in the mammalian brain.”

Why This Research Matters

Every neuron is a story, every dendrite a pathway of communication. By mapping these intricate structures, the UCLA team has illuminated the architecture of the brain with a precision never seen before. This research moves us closer to understanding how individual neurons contribute to behavior, how circuits are organized, and how diseases reshape the neuronal landscape.

In practical terms, dendritome mapping may one day help scientists identify early signs of neurodegenerative or psychiatric disorders, track disease progression, and even design targeted interventions. It bridges the gap between molecular identity and morphological form, offering a more complete picture of brain function.

In the hidden forest of the brain, the work of Yang, Park, and their colleagues is a lantern. It allows us to see the branches, the connections, and the patterns that make thought, movement, and memory possible. By exploring these pathways, we not only understand the brain more deeply but also take steps toward healing it when disease obscures its light.

The forest of neurons is vast, but with each branch illuminated, we come closer to understanding the very essence of what it means to think, feel, and live.

More information: Chang Sin Park et al, Dendritome mapping reveals the spatial organization of striatal neuron morphology, Nature Neuroscience (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41593-025-02085-z.