When most people think about early parenting, they picture mothers as the biological anchors of nurturing—breastfeeding, carrying, soothing, and responding instinctively to their infant’s needs. Fathers, by contrast, have historically been cast in supporting roles, providers rather than primary caregivers. But modern neuroscience is revealing a different truth: fatherhood leaves its own profound imprint on the human brain.

A new study from psychologists at the University of Southern California uncovers how first-time fathers’ brains light up in response to their own infant—stronger, in fact, than when they look at unfamiliar babies or even their romantic partners. The results are not only striking but deeply human, suggesting that fatherhood reshapes the mind in ways that foster bonding, protect against stress, and perhaps explain the invisible threads of connection that tie dads to their newborn children.

Why Infant Faces Are So Powerful

Human infants are born uniquely helpless. Unlike many other animals that can walk, climb, or feed themselves within hours of birth, a human baby depends almost entirely on adults for survival. Nature, in turn, equips babies with powerful tools to elicit care.

Consider the infant face. A newborn’s head is disproportionately large—already about a quarter of its adult size—yet the eyes are almost three-quarters grown, giving them that wide-eyed, gaze-capturing appearance. Their cheeks are round and chubby, their chin small, their forehead broad. These proportions are not just cute; they are evolution’s design. Such features trigger caregiving behaviors in adults, a phenomenon described as the “baby schema.”

For decades, research has shown that mothers are especially attuned to infant cues, both through hormonal shifts during pregnancy and through neural changes that sharpen their sensitivity to their own child. Their brains, particularly regions involved in emotion, reward, and social processing, light up when they see their baby’s face. Fathers, however, have remained less studied. Until now.

Inside the Study: Fathers, Brains, and Babies

The study, titled “My Baby Versus the World: Fathers’ Neural Processing of Own-Infant, Unfamiliar-Infant, and Romantic Partner Stimuli,” published in Human Brain Mapping, recruited 32 first-time fathers from the Los Angeles area.

When their babies were three months old, fathers filled out detailed questionnaires about their bonding experiences, parenting stress, and emotional adjustment to fatherhood. A few months later, when their infants were about eight months old, the fathers returned for an fMRI brain scan at USC’s Dornsife Cognitive Neuroimaging Center.

Inside the scanner, the men watched five-second silent video clips. Some showed their own baby. Others showed an unfamiliar infant. Still others featured their pregnant partner or an unfamiliar pregnant woman. The fathers rated each video on how pleasant or unpleasant it felt, but the real insights came from the neural activity captured by the fMRI.

A Father’s Brain Lights Up

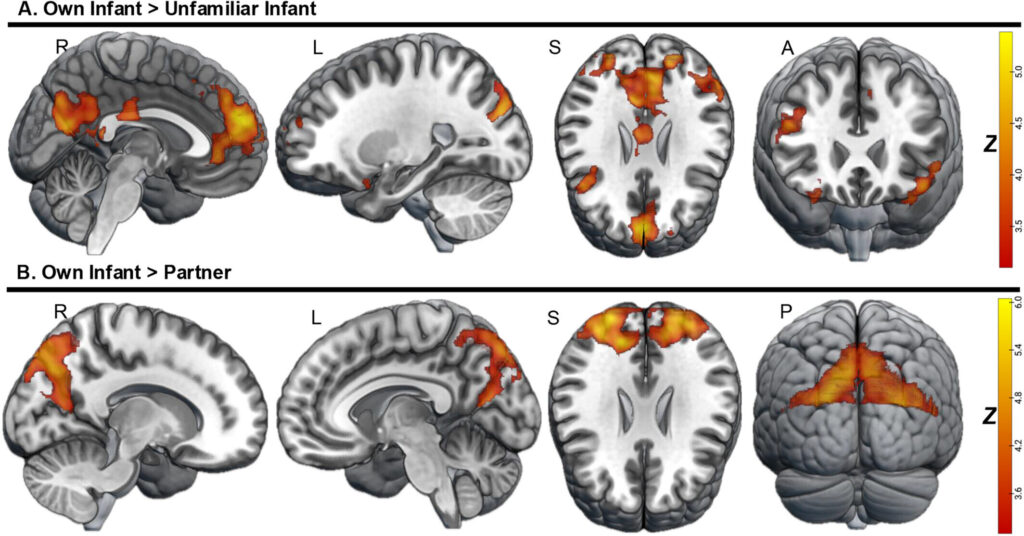

The results were unambiguous: first-time fathers’ brains were especially responsive to their own infants. Compared to watching unfamiliar babies, seeing their own child activated key brain regions associated with emotion, memory, reward, and social cognition.

Areas such as the precuneus, posterior cingulate cortex, anterior prefrontal cortex, orbitofrontal cortex, and temporal pole showed heightened activation. These regions play roles in everything from mentalizing—that is, understanding another’s perspective—to regulating emotion and evaluating social rewards.

Perhaps most strikingly, when fathers saw their own infant compared to their romantic partner, brain activity still tilted strongly in favor of the baby. The precuneus and posterior cingulate cortex, regions deeply tied to self-reflection and empathy, showed large surges in activation.

Bonding, Stress, and the Brain

The story didn’t end with brain scans. The researchers compared neural activity with fathers’ earlier questionnaire responses on bonding and stress. The results revealed a delicate dance:

- Stronger activation in the precuneus/posterior cingulate correlated positively with feelings of bonding.

- The same activation was linked inversely with parenting stress and bonding problems.

In other words, fathers whose brains showed a powerful response to their own infants also reported closer emotional ties and less stress. Neural sensitivity, it seems, may be both a marker and a driver of healthy father-infant relationships.

The Evolutionary Story Behind Fatherhood

Why does the brain of a father, not just a mother, tune so sharply to an infant’s cues? Evolution offers a clue. Human offspring require years of care before they can survive independently. Cooperative parenting—shared responsibilities between mothers and fathers—may have been critical to human survival. Fathers who were neurologically wired to respond to their infants likely had children who thrived, passing along these traits to future generations.

The USC findings highlight this possibility: far from passive participants in parenting, fathers are biologically and neurologically equipped to bond, nurture, and protect.

The Emotional Dimension

For fathers reading this, the results may resonate deeply. The first time a baby locks eyes with their dad, or curls a tiny fist around his finger, something powerful shifts. It is more than sentiment—it is biology. The rush of tenderness, the sense of responsibility, the willingness to lose sleep, change diapers, and rock a crying child in the dead of night—these are rooted in both love and the intricate architecture of the brain.

Fatherhood is not an afterthought in the grand story of human parenting. It is a transformative journey, one that reshapes not just daily life but the very circuits of the mind.

Toward a Fuller Understanding of Parenthood

The USC study is a step forward in filling a gap in research. While mothers’ brains have been studied extensively, fathers are only beginning to receive similar attention. These findings suggest that neuroscience can help illuminate the struggles and triumphs of early fatherhood, from bonding to coping with stress.

More broadly, they challenge outdated cultural narratives. Fathers are not biologically distant or emotionally secondary. They are wired—quite literally—for connection.

Conclusion: A New Picture of Fatherhood

Science is showing us what many fathers already feel in their hearts: that their bond with their child is powerful, natural, and essential. The USC researchers have revealed a neurological mirror of this truth, mapping how the father’s brain lights up in the presence of his own baby.

In those fleeting seconds of a baby’s smile or the tender weight of a child resting on his chest, the father’s brain is not passive. It is alive, reshaping itself to prioritize this new, fragile, beloved life.

Fatherhood, like motherhood, is not only a social role. It is a profound transformation written into the very circuits of the human mind.

More information: Philip Newsome et al, My Baby Versus the World: Fathers’ Neural Processing of Own‐Infant, Unfamiliar‐Infant, and Romantic Partner Stimuli, Human Brain Mapping (2025). DOI: 10.1002/hbm.70324