In a quiet lab at Stanford University, light and atoms dance together inside a pair of mirrors. The light bounces, scatters, and returns—forming intricate patterns invisible to the naked eye. To an untrained observer, it might seem like an elegant light show. But to physicists, what’s happening inside that mirrored cavity is something extraordinary: the realization of a new kind of spin glass—a state of matter so complex and mysterious that it has fascinated scientists for decades.

This experiment is not just about physics. It’s about the deep connection between matter, energy, and the architecture of thought. It is about finding the hidden parallels between the tangled spins of atomic magnets and the tangled neurons of the human brain.

What Are Spin Glasses?

To understand the magnitude of Stanford’s achievement, it helps to begin with the idea of a spin glass.

In physics, “spin” refers to a fundamental property of particles related to magnetism. Each spin behaves like a tiny magnet that can point either up or down. In a simple magnet, all these spins align in the same direction, producing a strong, uniform magnetic field. But in a spin glass, the situation is far messier.

Here, the spins are arranged randomly, with some preferring to align parallel to their neighbors and others preferring to point in opposite directions. No arrangement can satisfy all preferences at once. The result is a tangled, frustrated network of interactions, where each spin’s decision affects every other spin’s behavior.

This concept of frustration—where competing interactions prevent a system from settling into a simple, ordered state—makes spin glasses fascinating and difficult to understand. They don’t freeze into neat patterns but into chaotic landscapes filled with countless nearly stable configurations. In many ways, they mirror the unpredictability and complexity of the human brain.

A Decade in the Making

For more than ten years, physicist Benjamin Lev and his team at Stanford University have pursued an audacious dream: to create a spin glass not from magnetic materials, but from atoms and light. Their goal was to engineer a driven-dissipative Ising spin glass inside a special optical setup called a cavity quantum electrodynamics (QED) system.

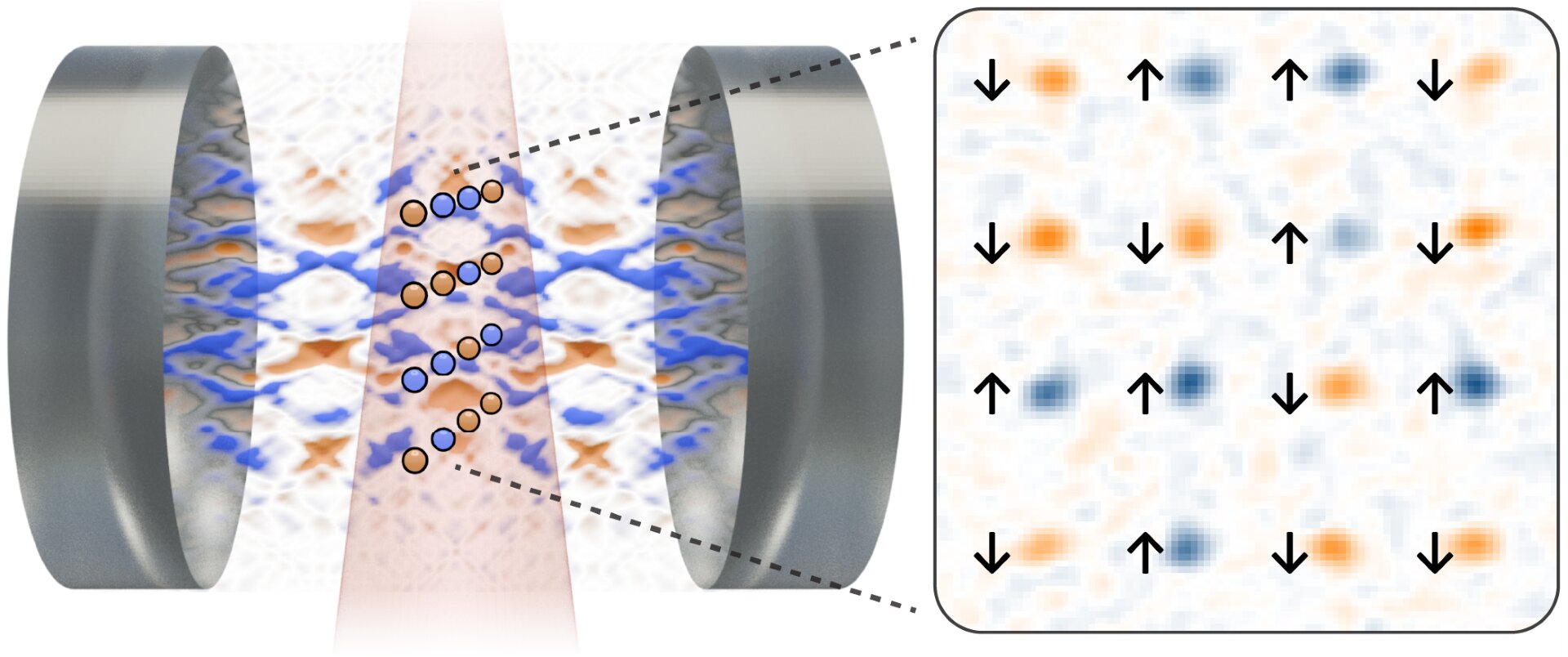

In this setup, atoms interact not directly with each other but through the photons bouncing between two mirrors. The light acts as a messenger, carrying information between atoms and connecting their spins in intricate, tunable ways.

Lev and his collaborators began their journey in 2010, guided by a simple yet daring question: What kind of neural networks could we build if we used quantum spins connected by light instead of electronic circuits?

The question connected two seemingly distant worlds—quantum physics and neuroscience. If neurons could be replaced by atomic spins and their synapses by photon-mediated connections, then perhaps one could build neuromorphic systems—machines that mimic how the brain processes information, learns, and remembers.

Building a Quantum Brain

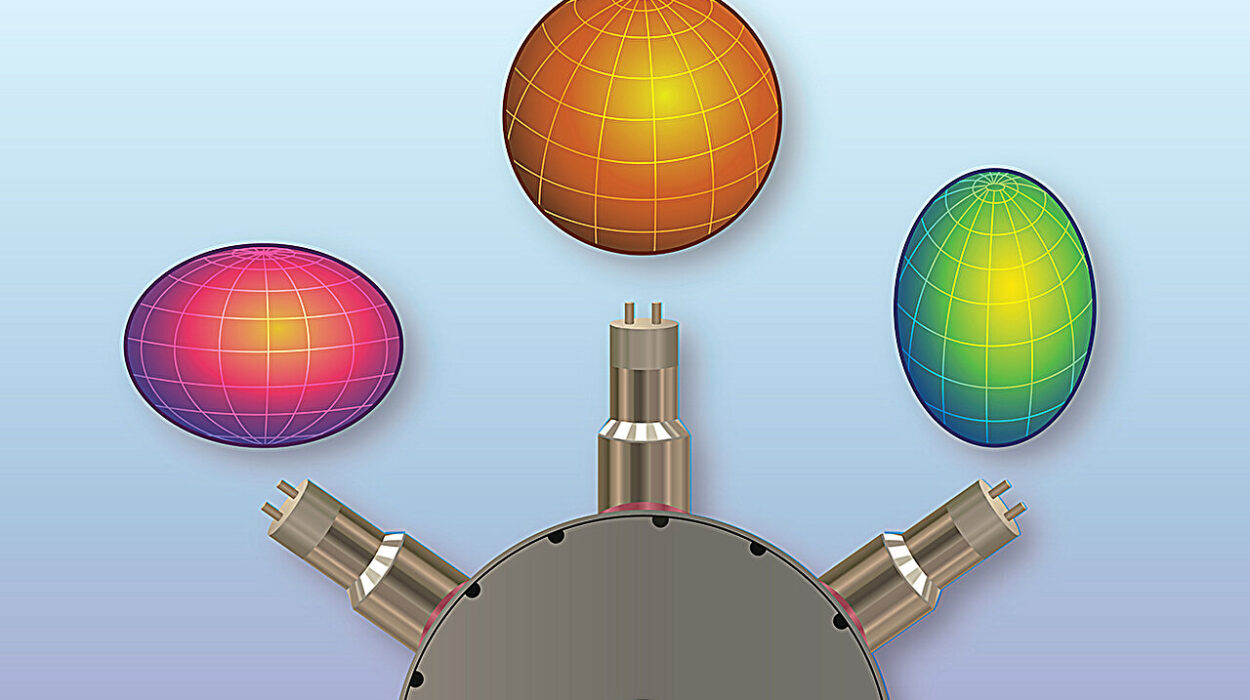

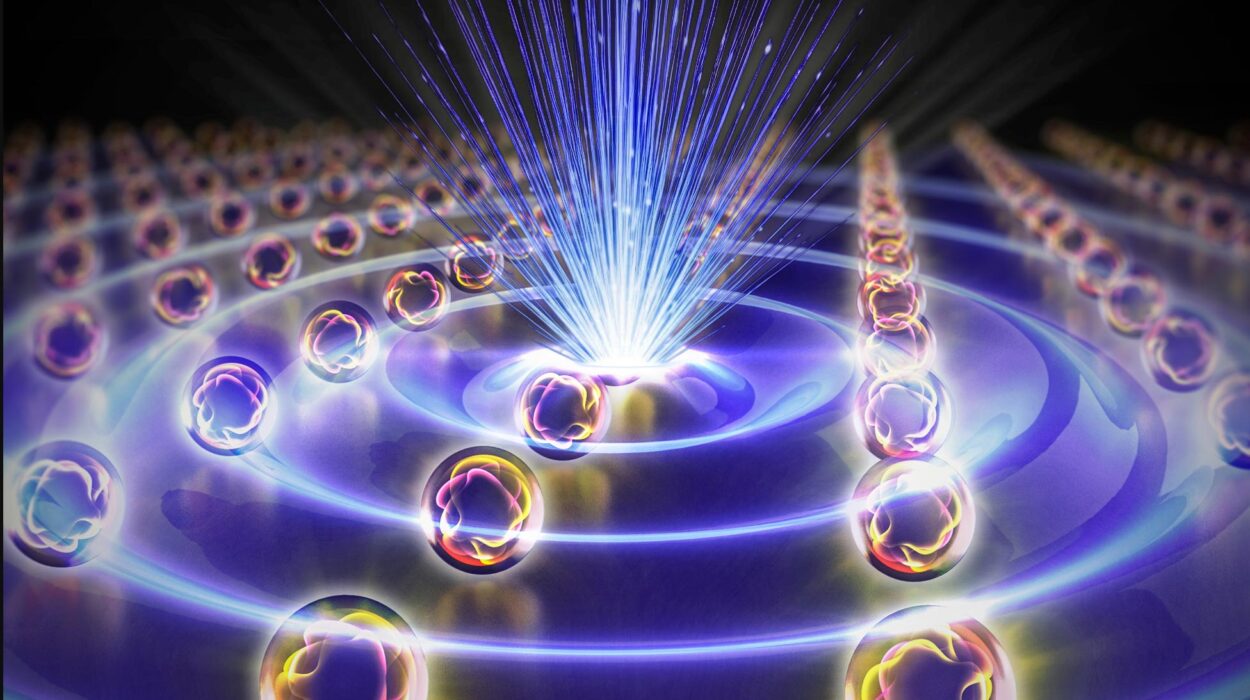

To make this vision real, Lev’s team turned to a form of cavity QED known as multimode cavity QED. Unlike traditional optical cavities that support a single mode of light bouncing between mirrors, a multimode cavity supports many spatial patterns of photons simultaneously.

Each of these modes can carry a distinct pattern of light intensity and phase, allowing atoms trapped inside to interact in highly complex and variable ways. By precisely tuning the mirrors and geometry, the researchers could “wire up” atomic spins with randomly signed connections—much like the tangled web of synapses in a brain.

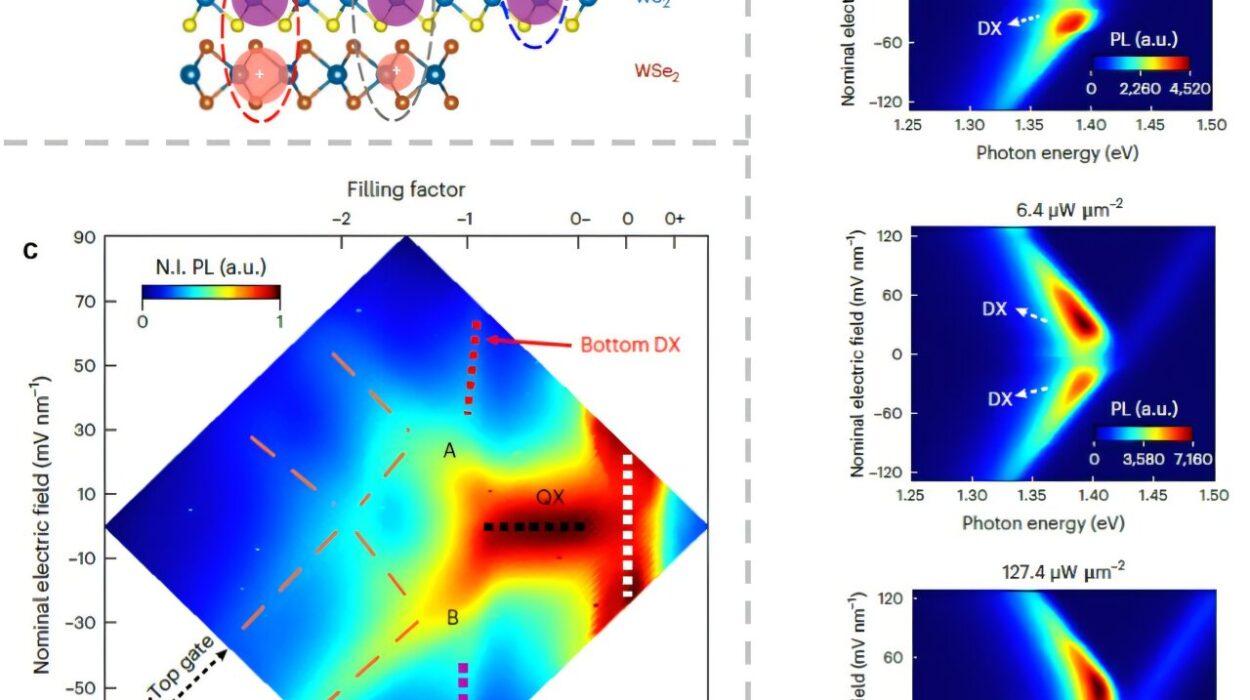

But turning theory into experiment was no small feat. Over several years, Lev’s group built a series of setups, refining their control over atoms and light. By 2015, they had experimentally benchmarked how multimode cavity QED behaved. In 2017, they achieved their first breakthrough—creating a strange type of spin glass where atomic spins interacted through light in patterns known as XY or XX–YY couplings.

It was a milestone, but not the end goal. To truly mimic neural networks, they needed an Ising spin glass—the canonical form where spins interact in binary up-or-down states. That required a new optical design capable of producing the right kind of photon-mediated interactions.

The Birth of the Ising Spin Glass

In collaboration with theorist Jonathan Keeling and undergraduate student Rhiannon Lunney at the University of St. Andrews, the team developed a new type of multimode cavity. Their design, dubbed the “4/7 cavity”, allowed the photons to mediate the right kind of all-to-all spin interactions necessary to form an Ising spin glass.

This new optical resonator was engineered so that light could scatter in a particular way between the mirrors, creating thousands of overlapping spatial patterns. Each mode connected every atom to every other atom with randomly positive or negative couplings—a quantum version of a chaotic neural network.

When they finally tuned the system and trapped ultracold atoms inside, the researchers observed something never seen before: a driven-dissipative Ising spin glass formed entirely from light and matter.

In this system, the atomic spins were coupled by photons bouncing inside the cavity. The atoms could move slightly, altering how they scattered light, which in turn changed the interactions among them. The resulting network of feedbacks produced a dynamically frustrated, glass-like state—a frozen pattern of correlations that could store and retrieve information.

Seeing the Invisible

One of the remarkable achievements of Lev’s experiment is that it allows direct visualization of the spin configuration.

As the light leaks from the cavity, it carries information about how the atoms are arranged—essentially, a hologram of the system’s internal state. By analyzing this escaping light, the researchers could reconstruct the pattern of spins, revealing how the glass organizes itself microscopically.

This capability is revolutionary. For decades, physicists have studied spin glasses indirectly, inferring their properties from bulk measurements. Now, with this quantum-optical setup, scientists can see the microscopic structure of a glassy system as it evolves in real time.

The setup functions like an “active quantum gas microscope,” combining precision imaging with control over photon-mediated interactions. It not only observes atomic behavior—it shapes it, allowing the researchers to create and manipulate exotic states of matter at will.

The Memory of Light

Perhaps the most intriguing result of the experiment is that this spin glass behaves like a kind of memory device.

When the system is driven by light, patterns of atomic alignment can become imprinted into the cavity field. Later, when stimulated again, the system can reproduce those patterns—retrieving the stored information, much like how the brain recalls memories.

Lev’s group demonstrated that their Ising spin glass could perform associative memory, a process where the system recognizes and recalls a stored pattern even from partial input. Remarkably, their atomic system outperformed the classic Hopfield model, a foundational mathematical model of artificial neural networks.

This suggests that quantum-optical systems might one day form the basis for new kinds of neuromorphic hardware—machines that compute and learn not through digital circuits but through the physics of light and matter.

Even more surprising, the researchers found signs of short-term learning plasticity—a behavior reminiscent of the way biological synapses strengthen or weaken based on experience. In their system, this plasticity emerged naturally from the feedback between atoms and photons.

The Dance of Spins and Light

Inside the cavity, the interaction between atoms and light is a subtle dance. The atoms are cooled to near absolute zero, forming a Bose-Einstein condensate—a state where thousands of atoms behave as one quantum entity.

When light enters from the side, it scatters off the atoms, creating interference patterns. These patterns correspond to two distinct “checkerboard” arrangements, representing the two possible spin states: spin-up or spin-down.

The multimode cavity enables the creation of localized photon patterns, called supermodes, that mediate these spin interactions. Depending on the phase of the light striking each atom, spins are encouraged to align or oppose each other, forming a complex web of connections that spans the entire cavity.

This randomness in the interactions—the heart of frustration—is what gives rise to the glassy nature of the system. The photons continually interact with the atoms, leaking out of the cavity and carrying with them the information of the spins’ collective state.

Beyond Equilibrium

Unlike ordinary solids or magnets that settle into equilibrium, glasses are non-equilibrium systems. They can get stuck in metastable states—configurations that last indefinitely even though they aren’t the system’s true lowest-energy state.

Lev’s spin glass takes this a step further. It’s a driven-dissipative system, meaning energy continuously flows in and out through the photons. The spins never truly settle; they live in a delicate balance of drive and dissipation. This makes the system not just physically rich, but a perfect laboratory for studying non-equilibrium physics—a frontier where theory still struggles to keep up.

With 25 interacting spins, the system is already too complex for classical computers to simulate accurately. It represents a bridge between classical and quantum regimes—a model of complexity that exists beyond the reach of calculation, yet within the grasp of experimental control.

Toward Quantum Neuromorphic Computing

The implications of this work reach far beyond condensed matter physics. Lev’s Ising spin glass points toward a new generation of computational devices that blend the power of quantum mechanics with the adaptive flexibility of biological brains.

Unlike digital computers that process information step by step, neuromorphic systems compute through networks of interconnected units, much like neurons firing together in a brain. The Stanford team’s system uses spins as these artificial neurons, with photons as the connections that mediate learning and memory.

By adjusting the cavity geometry and laser parameters, the researchers can tune the connectivity of this “quantum brain,” exploring how different network topologies affect its ability to store and recall information.

A Window into Complexity

The realization of this quantum-optical spin glass marks a profound step in physics. It merges ideas from magnetism, optics, quantum mechanics, and neuroscience into a single experimental platform.

For decades, scientists have sought to understand how order and chaos coexist in complex systems—from disordered materials to living organisms to human thought itself. Lev’s experiment provides not only a physical model for these phenomena but also a potential bridge between natural intelligence and artificial computation.

As the researchers now move toward making their spins behave more quantum mechanically, they hope to create and explore quantum-entangled spin glasses—systems in which the tangled patterns of frustration are enriched by quantum correlations. Such systems could reveal how memory, learning, and complexity emerge from the fundamental laws of physics.

The Human Connection

What makes this story so captivating is not just the technology or the physics, but the human drive behind it. For over a decade, Benjamin Lev and his collaborators pursued a vision that many might have thought impossible. They imagined a world where light could mimic thought, where atoms could remember, and where the rules of the universe might reveal the hidden logic of the mind.

Their success is a testament to patience, creativity, and the power of scientific imagination.

Inside their mirrored chamber, thousands of photons and atoms interact in perfect harmony, forming a miniature universe that blurs the line between matter and thought. In that shimmering world of light and quantum motion, we see a reflection—not only of the universe’s complexity but also of our own.

The realization of the driven-dissipative Ising spin glass is more than a breakthrough in physics. It is a glimpse into the deep unity between nature’s laws and the architecture of intelligence—a reminder that the mind itself may, at its deepest level, be written in the language of light.

More information: Brendan P. Marsh et al, Multimode Cavity QED Ising Spin Glass, Physical Review Letters (2025). DOI: 10.1103/x19r-pzyb. On arXiv: DOI: 10.48550/arxiv.2505.22658