Few archaeological finds have gripped the imagination of the modern world quite like the Dead Sea Scrolls. Hidden in desert caves for over two millennia and rediscovered only in the mid-20th century, these ancient manuscripts have been called the greatest biblical discovery of the 20th century. They cracked open the door to Jewish life and theology during a critical moment in history—when Judaism and early Christianity were emerging as distinct religious traditions. For decades, scholars have puzzled over their age and provenance, leaning heavily on paleography—the study of ancient handwriting—to estimate when these mysterious texts were written. But a breakthrough has changed everything.

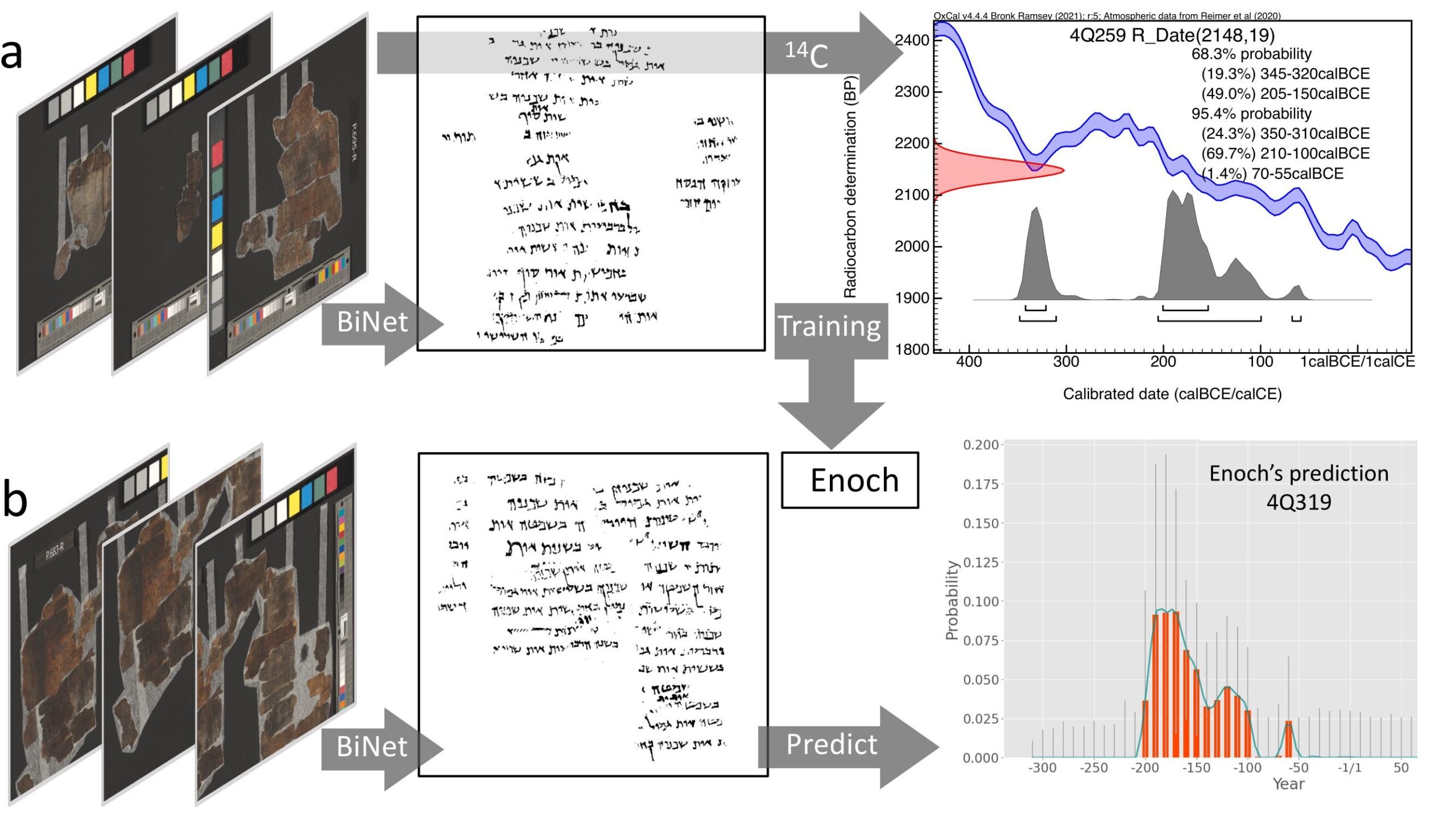

An international team led by the University of Groningen has recently announced the development of Enoch, an innovative, machine-learning-based model that integrates paleography with the empirical power of radiocarbon dating. This tool is not only redating the Dead Sea Scrolls—it’s rewriting the very timeline of biblical and religious history.

A New Science for Ancient Scripts

Traditionally, dating ancient manuscripts like the Dead Sea Scrolls relied on trained human eyes comparing handwritten scripts to a sparse set of dated samples. This method, though grounded in scholarly expertise, was necessarily subjective and fraught with uncertainties. There’s a major chronological gap between the few known date-bearing Hebrew or Aramaic manuscripts from the 5th–4th centuries BCE and the better-dated materials from the 1st–2nd centuries CE. This left more than a thousand scrolls from Qumran in a kind of scholarly limbo, assigned broad estimates but lacking precise dates.

To bridge this centuries-long gap, the research team employed radiocarbon dating on 24 Dead Sea Scroll samples. This physical dating technique, based on the decay of carbon-14 isotopes, is a cornerstone of modern archaeology, providing reliable age estimates for organic materials. But radiocarbon dating, while powerful, has its own limitations—particularly when dating texts from between 300–50 BCE, where its precision is diluted due to calibration curve plateaus.

The researchers recognized that the answer lay not in choosing between handwriting analysis and radiocarbon dating, but in marrying them, and enhancing them both with modern computing power.

The Birth of Enoch: Deep Learning Meets Ancient Ink

Enter Enoch, named after the ancient Jewish scribe of apocryphal fame. This AI model was designed to predict manuscript dates using paleography—only this time, enhanced with the mathematical rigor of Bayesian ridge regression and deep neural networks.

The foundation of Enoch’s abilities is an earlier model called BiNet, developed to detect ink-trace patterns in digitized manuscripts. BiNet’s genius lies in its attention to microscopic handwriting features—the subtle curvature of strokes, the spacing and pressure of ink, and the tiny inconsistencies that reflect not only the individual scribe’s hand but also broader script traditions of their time.

Using high-resolution scans of Dead Sea Scroll fragments, BiNet transformed these images into datasets of ink geometry. These features were then processed by Enoch to produce highly accurate date predictions. The model cross-validated its findings against known radiocarbon dates, achieving an uncertainty range of just ±30 years—even tighter than radiocarbon dating alone for certain periods.

This means that for texts written over 2,000 years ago, we can now estimate their date of origin within half a century. The implications are revolutionary.

Unmasking the Chronology of Script Styles

The first significant revelation from Enoch’s predictions is that many of the Dead Sea Scrolls are older than previously believed. This forces a re-evaluation of the evolution of ancient Hebrew scripts, especially two dominant styles found in the scrolls: Hasmonaean and Herodian.

Until now, Hasmonaean script was believed to have emerged around 150–50 BCE. But Enoch’s results show that some scrolls written in this style predate this estimate by decades—if not more. Likewise, the Herodian script, traditionally placed in the mid-1st century BCE, appears to have been in use as early as the late 2nd century BCE.

This means that these two styles coexisted for a longer period than previously thought, and their usage likely reflected a more complex and regionally varied scribal culture in Judaea. By mapping script evolution more precisely, historians can now better understand how scribes operated under different political regimes—such as the Seleucid, Hasmonaean, and Roman powers—and how these changes influenced script choices and textual traditions.

From Script to Scribes: Identifying Authors in Biblical Time

Perhaps the most electrifying breakthrough enabled by Enoch is its ability to link specific biblical scrolls to the historical periods of their presumed authors—a feat never before possible.

Two fragments in particular have stunned the scholarly community:

- 4QDanielc (4Q114), a portion of the Book of Daniel

- 4QQoheleta (4Q109), a fragment of the Book of Ecclesiastes

The Book of Daniel is thought to have been completed in the early 160s BCE, during the reign of the Seleucid Empire. Ecclesiastes, on the other hand, is widely considered to be a product of the 3rd century BCE, reflecting Hellenistic influence in post-exilic Judaism.

Radiocarbon dating and Enoch’s predictions place these fragments squarely within these timeframes, strongly suggesting that they were written contemporaneously with their final redaction. This is a landmark moment in biblical studies. For the first time, scholars can hold in their hands a manuscript that was likely penned by the very generation that authored the biblical book itself.

This also supports a growing view that many parts of the Hebrew Bible were not written centuries earlier by legendary figures such as Moses or Solomon, but rather by anonymous scribes during the Second Temple period—a time of political turmoil, theological innovation, and burgeoning sectarianism.

Literacy, Politics, and Religion in a New Light

The implications of this new dating model go beyond the margins of ancient manuscripts. They spill over into broader questions about literacy, identity, and religion in the Hellenistic and early Roman Near East.

With Enoch enabling precise dating, historians can now chart the rise of literacy in ancient Judaea and its correlation with historical events like the Maccabean Revolt, the reign of the Hasmonaean dynasty, and the sectarian ferment that birthed groups like the Essenes and, eventually, Christianity.

The updated timeline also aligns with shifts in material culture—urban development, increased use of Greek and Aramaic alongside Hebrew, and the theological tensions seen in scrolls like the Damascus Document or the Community Rule.

By firmly dating these texts, scholars can more confidently associate them with specific social movements, theological debates, or political reactions. For example, a legal scroll once thought to reflect Roman-era concerns might instead reveal Jewish thought during the Seleucid oppression.

Enoch transforms the scrolls from isolated religious artifacts into time-stamped voices of their age, embedded in the currents of history.

The Future of Manuscript Archaeology

The development of Enoch is not merely a triumph for biblical studies—it’s a paradigm shift in how we date ancient texts. Its transparent, explainable architecture allows researchers to see why the model makes certain predictions, making it a tool that supports human judgment rather than replaces it.

And Enoch’s applications extend far beyond the Dead Sea Scrolls. Any ancient manuscript collection with at least some dated material—such as the Oxyrhynchus papyri, the Nag Hammadi library, or early Islamic texts—can now benefit from this approach.

Moreover, Enoch represents a rare confluence of humanistic scholarship and artificial intelligence. It leverages the rigor of computational analysis while honoring the complexities of ancient culture, script, and history. In doing so, it embodies a new kind of scholarship—one that is collaborative, interdisciplinary, and empirically grounded.

Conclusion: Rewriting History, One Letter at a Time

The Dead Sea Scrolls have always whispered secrets from antiquity. But for decades, scholars struggled to make out the contours of their timelines. Now, with Enoch, those whispers have become intelligible.

Thanks to this marriage of radiocarbon physics, handwriting geometry, and artificial intelligence, we can now date ancient scriptures with astonishing precision. And with that precision comes clarity—a sharper view of how Judaism and Christianity emerged, how ancient scribes operated, and how scripture itself evolved through turbulent centuries.

Enoch is more than a dating tool. It is a time machine made of mathematics, peeling back the centuries and letting us stand—digitally and intellectually—beside the hands that wrote the Bible.

Reference: Mladen Popović, et al. Dating ancient manuscripts using radiocarbon and AI-based writing style analysis, PLOS One (2025). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0323185