High above Earth, aboard the International Space Station, a state-of-the-art NASA instrument scans the surface of the planet with the precision of a scientific detective. It was designed to map desert dust and minerals, but recently, it uncovered something very different: the spectral signature of sewage swirling in the waters off Southern California.

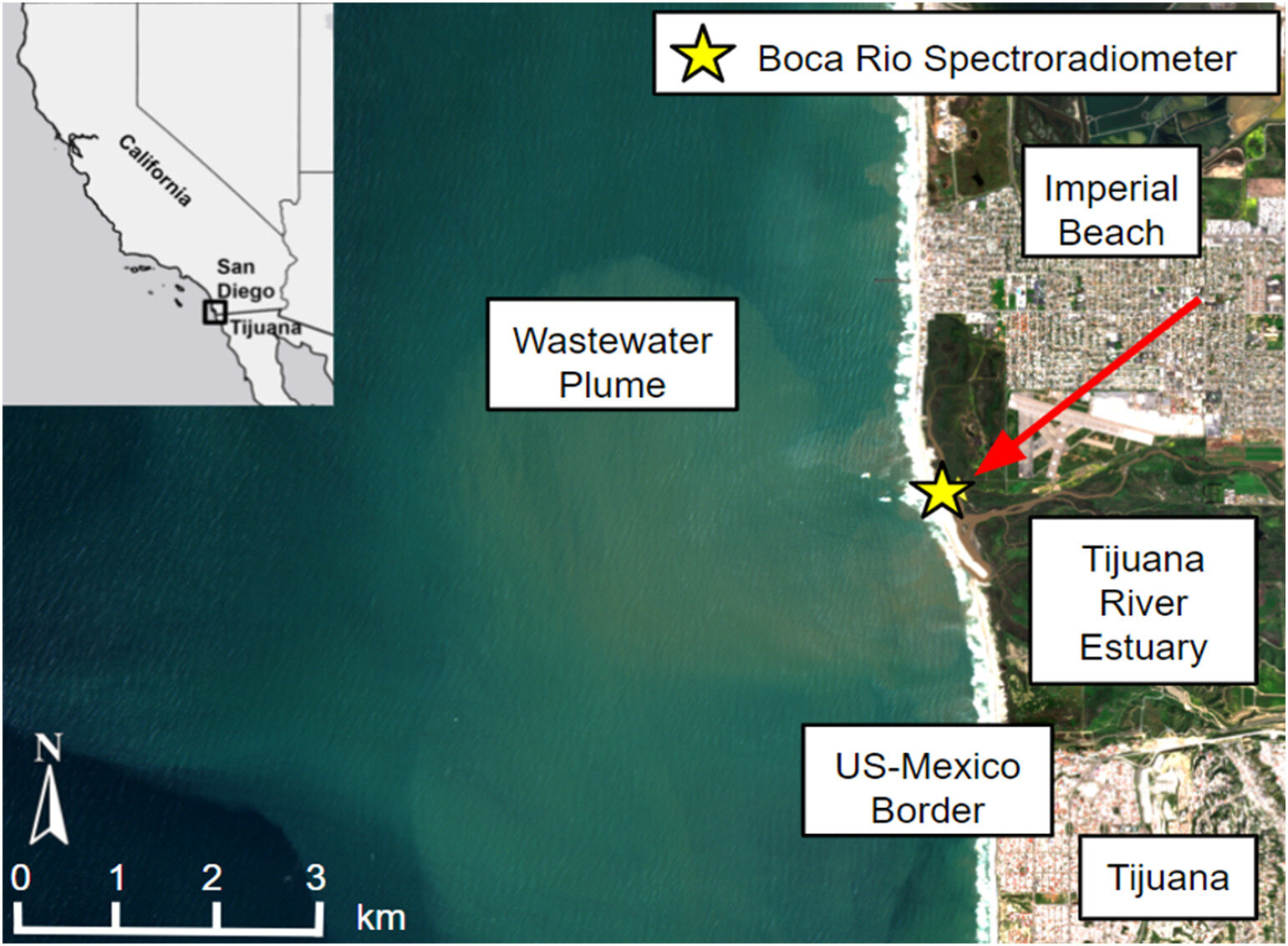

The discovery, detailed in a study published in Science of The Total Environment, marks a turning point in how scientists monitor water pollution from space. Using NASA’s Earth Surface Mineral Dust Source Investigation, or EMIT, researchers identified clear signs of wastewater contamination in the Pacific Ocean at the mouth of the Tijuana River—a region notorious for chronic pollution that has long plagued beachgoers, wildlife, and local communities.

This time, the culprit left a spectral fingerprint. And for researchers tracking the health of coastal ecosystems, it’s a breakthrough that could change the game.

A River of Trouble

The Tijuana River flows through both Mexico and the United States, crossing the international border before emptying into the Pacific near Imperial Beach, just south of San Diego. But for decades, the river has also been a conduit for pollution—carrying millions of gallons of treated and untreated sewage through a protected estuarine reserve and into the ocean.

The impacts are wide-reaching. Contaminated waters can cause illness in humans who swim, surf, or simply walk along the coast. They endanger marine life and fisheries. They even disrupt training for U.S. Navy recruits, who often drill in the affected zones. On bad days, entire stretches of Southern California’s beaches are closed, ringed with red flags and dire warnings.

Monitoring such contamination has never been easy. Traditional satellite sensors can track visible signs of water quality issues—such as the brilliant greens and reds of harmful algal blooms—but they often miss the subtler signals of bacteria and sewage-related pollutants.

That’s where EMIT makes a dramatic entrance.

A New Eye in the Sky

EMIT wasn’t designed to monitor oceans. When it launched aboard the ISS in July 2022, its mission was clear: map the mineral composition of the planet’s arid regions to better understand how dust affects climate.

But the instrument’s strength—its ability to split reflected sunlight into hundreds of narrow color bands—gave scientists a hunch: maybe this same hyperspectral technology could detect more than just dry Earth. Maybe, just maybe, it could peer into coastal waters and find the invisible.

It worked.

In the recent study, researchers from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), San Diego State University, and the University of Connecticut compared EMIT’s data with water samples taken directly from the Tijuana River plume. What they found was striking. EMIT’s spectral readout captured a distinct signal associated with phycocyanin, a pigment found in cyanobacteria—a type of harmful bacteria that thrives in nutrient-rich, polluted waters and poses health risks to humans and animals alike.

“It’s like a diagnostic at the doctor’s office that tells you, ‘Hey, let’s take a closer look at this,’” said Christine Lee, a JPL scientist and co-author of the study. “From orbit, you can see that a wastewater plume is extending into places you haven’t sampled.”

The Smoking Gun

For lead author Eva Scrivner, a doctoral student at the University of Connecticut who led the study while at San Diego State, the discovery felt like something more: proof that EMIT could spot the chemical signature of pollution in real-world conditions.

“It shows a ‘smoking gun’ of sorts for wastewater in the Tijuana River plume,” Scrivner said. “That fingerprint of phycocyanin is consistent with what we know from field tests—it’s not just visible pollution, it’s molecular.”

Scrivner noted that this approach could help fill critical data gaps at polluted sites where traditional monitoring is expensive and time-consuming. With EMIT, entire stretches of coastlines could be assessed in seconds—without waiting days for lab results.

The implications are global. Rivers across the world flush untreated wastewater into oceans, lakes, and bays. If EMIT can detect these signs from low Earth orbit, it could become a vital tool for countries and communities struggling to monitor pollution in real time.

A New Chapter for an Old Technology

The technology behind EMIT—called imaging spectroscopy—has a long pedigree at JPL. Since the 1980s, imaging spectrometers developed at the Pasadena-based lab have been used to study everything from wildfires to forests to agriculture. These instruments can “see” wavelengths of light invisible to the human eye, identifying materials based on how they absorb and reflect different parts of the spectrum.

When EMIT was launched, it was lauded as a climate mission—its goal to help model how mineral dust affects Earth’s temperature and cloud formation. But like many of NASA’s most successful tools, its utility turned out to be far broader than expected.

“The fact that EMIT’s findings over the coast are consistent with measurements in the field is compelling to water scientists,” Scrivner said. “It’s really exciting.”

Indeed, the instrument’s hyperspectral sensitivity, once aimed only at deserts, has opened a new frontier: the ability to analyze water quality with unprecedented detail and speed.

Beyond California’s Shores

The Southern California test case is just the beginning. Researchers believe that EMIT—and future instruments built on its technology—could scan coastlines across the globe, identifying pollution hot spots and helping governments make faster, better-informed decisions.

It’s especially promising for places with limited resources for field sampling. A hyperspectral satellite could alert local authorities to potential contamination events before swimmers get sick or fish die off. It could help enforce pollution regulations, track the health of coral reefs, or even monitor illegal dumping.

But it’s not just about adding another satellite to the sky. It’s about changing how we think about Earth observation.

“Environmental science isn’t confined to land or ocean,” Lee said. “Our tools need to be as interconnected as the systems we’re trying to understand.”

A Turning Point for Pollution Monitoring

The detection of cyanobacterial pigments in the Tijuana River plume is more than a scientific milestone—it’s a glimpse into the future of environmental monitoring. One where real-time, molecular-level diagnostics could become as routine as weather forecasts.

For the millions living near coasts, swimming in oceans, or depending on fisheries, the promise of better pollution tracking is more than academic. It’s a matter of public health, ecological preservation, and justice.

And for EMIT, a mission that started with minerals in deserts has now become an unlikely guardian of our oceans.

From the quiet hum of an instrument on the International Space Station, new voices are rising in the fight for clean water. They are the voices of data, light, and spectra—revealing, pixel by pixel, the invisible truths swirling beneath the waves.

Reference: Eva Scrivner et al, Hyperspectral characterization of wastewater in the Tijuana River Estuary using laboratory, field, and EMIT satellite spectroscopy, Science of The Total Environment (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2025.179598