The internet is often imagined as something distant and immense, a vast cloud owned and operated by powerful corporations, humming quietly in data centers far from everyday life. We plug into it, pay monthly fees, accept its limitations, and rarely question its structure. Yet beneath this familiar surface lies a radical idea that is as old as human cooperation itself: what if communities could build their own internet, by themselves, for themselves? Mesh networks are the embodiment of that idea. They are not just a technical alternative to traditional connectivity but a social and political statement about autonomy, resilience, and shared responsibility.

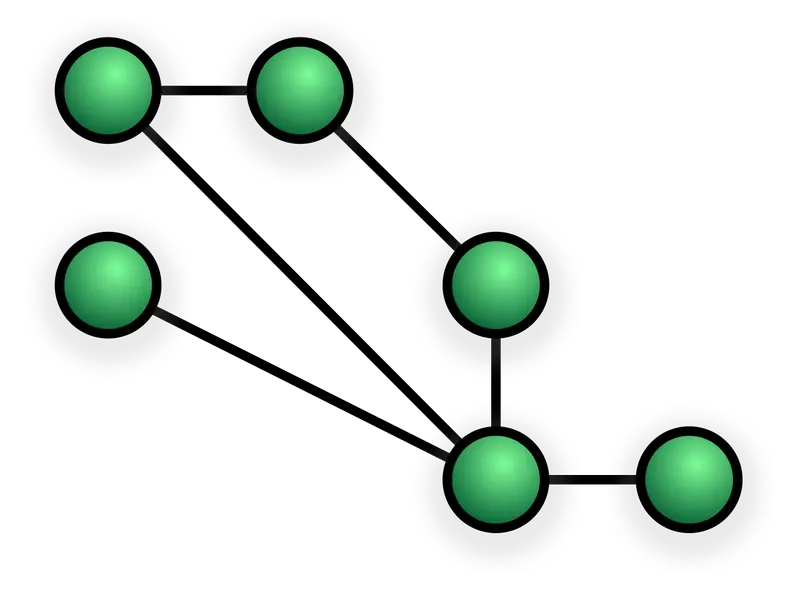

A mesh network is a network in which each device, or node, connects directly to several others, forming a web of interlinked paths. Instead of relying on a central hub or a single service provider, data travels from node to node until it reaches its destination. The network grows organically as more participants join, and its strength lies in cooperation rather than hierarchy. In mesh networks, the internet stops being a service delivered from above and becomes a living infrastructure shaped by the people who use it.

To understand why mesh networks matter, it helps to first understand how the internet usually works and where its weaknesses lie.

The Hidden Structure of the Internet We Know

Most people experience the internet as a seamless, ever-present utility, but its underlying structure is surprisingly fragile. Traditional internet access depends on centralized infrastructure. Internet service providers control physical cables, wireless towers, and routing equipment. Your connection typically travels from your device to a local router, then to your provider’s network, and from there across a series of large, centralized exchanges before reaching its destination.

This model is efficient and profitable, but it has consequences. When a central point fails, entire regions can lose connectivity. Natural disasters, power outages, political unrest, or simple technical faults can cut people off from communication at precisely the moments when they need it most. In many parts of the world, especially rural or economically marginalized areas, building centralized infrastructure is too expensive, leaving communities underserved or completely disconnected.

Even where connectivity exists, centralized control raises questions about surveillance, censorship, and access. Decisions about who gets connected, at what speed, and under what conditions are often made far away from the people affected by them. The internet, originally designed as a decentralized system, has in many ways drifted toward concentration of power.

Mesh networks emerge as a response to these vulnerabilities and imbalances. They are an attempt to reclaim the original spirit of the internet as a distributed, resilient, and community-driven system.

What a Mesh Network Really Is

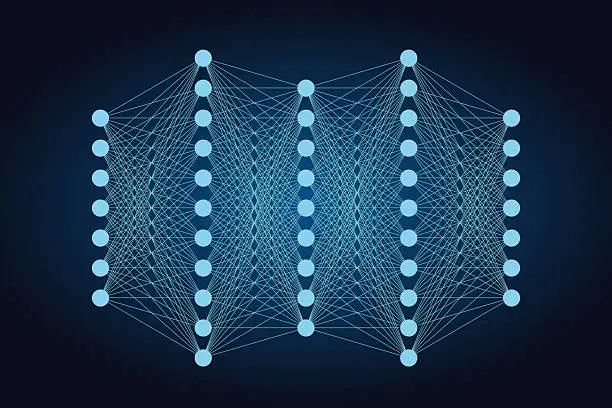

At a technical level, a mesh network consists of nodes that both consume and forward data. Each node can act as a router, passing information along to others. There is no single point of control and no required central server. If one node goes offline, the network can automatically reroute traffic through alternative paths.

This structure mirrors patterns found throughout nature. Ant colonies, neural networks, and ecosystems all rely on distributed interactions rather than centralized command. The intelligence of the system emerges from the relationships between its parts, not from any single component.

In a community mesh network, nodes might be home routers, rooftop antennas, small computers, or even smartphones configured to participate. Some nodes may have access to the wider internet through a gateway connection, while others rely entirely on peer-to-peer links. What matters is not uniformity but cooperation.

The technology behind mesh networking is well established. Wireless protocols allow devices to discover nearby peers and establish links automatically. Routing algorithms determine the best path for data to travel, taking into account signal strength, congestion, and reliability. These processes happen dynamically, adapting as the network changes.

Yet the technical description alone does not capture the deeper meaning of mesh networks. They are as much about people as they are about packets of data.

The Emotional Power of Local Connectivity

Imagine a neighborhood where internet access is unreliable or unaffordable. Instead of waiting for a provider to upgrade infrastructure, residents come together. Someone installs an antenna on a rooftop. Another configures a router. A third shares technical knowledge. Slowly, a network forms, connecting homes, schools, and community centers.

The emotional impact of this process is profound. Connectivity stops being something that happens to people and becomes something they create. The network reflects the geography, needs, and values of the community. Trust becomes a form of infrastructure. Participation replaces consumption.

In such networks, people often discover a renewed sense of agency. They learn how the internet works at a fundamental level, demystifying a technology that often feels opaque and intimidating. This knowledge fosters confidence and curiosity, especially among younger participants, who see that they can shape digital systems rather than merely adapt to them.

Mesh networks also create spaces for local content and services. Community forums, local news, educational resources, and cultural archives can exist entirely within the mesh, accessible even when the wider internet is down. The network becomes a digital commons, owned and maintained collectively.

Resilience in the Face of Failure

One of the most compelling advantages of mesh networks is resilience. Centralized networks are efficient under normal conditions but brittle under stress. When a critical link fails, the effects can cascade rapidly. Mesh networks, by contrast, are designed to expect failure and adapt to it.

Because data can take multiple paths, the loss of a single node rarely brings down the entire system. This makes mesh networks particularly valuable in disaster-prone areas. After earthquakes, hurricanes, or floods, traditional infrastructure may be damaged or overwhelmed. Mesh networks can continue to function, enabling communication when it is most urgently needed.

This resilience is not just technical but social. Communities that build and maintain their own networks develop skills and relationships that persist beyond any single crisis. The act of building a mesh network strengthens social bonds, making the community itself more resilient.

In some cases, mesh networks have been deployed rapidly in emergency situations, providing temporary communication where none existed before. In others, they serve as permanent infrastructure, quietly operating in the background, ready to take on greater importance when conventional systems falter.

Scientific Foundations of Mesh Networking

The principles behind mesh networks are grounded in well-established areas of science and engineering. At their core are concepts from graph theory, information theory, and wireless communication.

In graph theory, a network is represented as a set of nodes connected by edges. Mesh networks are characterized by high connectivity and redundancy, which increase the number of possible paths between nodes. This redundancy improves fault tolerance and load balancing, key properties for reliable communication.

Wireless communication relies on electromagnetic waves, which propagate through space and interact with physical obstacles. Signal strength decreases with distance and can be affected by interference, weather, and terrain. Mesh networks mitigate these challenges by using many short links instead of a few long ones. Each node only needs to reach nearby peers, reducing power requirements and improving reliability.

Routing protocols in mesh networks use algorithms that dynamically adjust to changing conditions. They measure link quality, detect failures, and choose routes that optimize performance. This adaptability is a direct application of control theory and distributed computing, fields that study how complex systems behave without centralized control.

From a scientific perspective, mesh networks are a practical demonstration of how decentralized systems can achieve robustness and efficiency through local interactions.

Community Networks and the Ethics of Access

Beyond technical considerations, mesh networks raise important ethical questions about access, ownership, and control. In many parts of the world, internet access is unevenly distributed. Economic barriers, geographic isolation, and political constraints leave millions without reliable connectivity.

Community-built mesh networks challenge the assumption that access must be provided by large corporations or governments. They offer a model in which connectivity is treated as a shared resource, managed collectively rather than commodified.

This model aligns with broader ethical principles of equity and inclusion. By lowering barriers to entry and encouraging local participation, mesh networks can help bridge digital divides. They allow communities to tailor solutions to their specific needs rather than relying on one-size-fits-all approaches.

However, ethical challenges also arise within mesh networks themselves. Decisions about governance, resource allocation, and acceptable use must be made collaboratively. Conflicts can emerge, requiring transparent processes and mutual respect. These challenges are not flaws but reflections of the reality that technology is inseparable from social dynamics.

Privacy, Surveillance, and Trust

In an era of widespread digital surveillance, privacy has become a central concern. Traditional internet traffic often passes through centralized servers where it can be monitored, logged, or filtered. Mesh networks offer an alternative model that can enhance privacy by keeping data local and reducing dependence on external intermediaries.

When communication stays within a community mesh, it is less exposed to external surveillance. Encryption can further protect data as it travels between nodes. Because the network is managed by the users themselves, policies about data retention and access can be shaped by shared values rather than imposed by distant entities.

At the same time, mesh networks rely heavily on trust. Participants forward each other’s data, creating interdependence. This trust is often reinforced by existing social relationships, but it also requires technical safeguards to prevent misuse. Designing systems that balance openness with security is an ongoing challenge, one that reflects broader tensions in digital society.

Education and the Democratization of Technology

Mesh networks are powerful educational tools. Building and maintaining a network requires understanding hardware, software, radio communication, and network protocols. These skills are highly transferable and can open doors to further learning and employment.

When communities engage in mesh networking, education becomes experiential rather than abstract. People learn by doing, solving real problems in their own environment. This hands-on approach demystifies technology and challenges the notion that advanced systems are only for experts.

For young people in particular, participation in a mesh network can be transformative. It shows that technology is not magic but something understandable and malleable. It encourages critical thinking and creativity, nurturing a generation that sees itself as capable of shaping digital futures.

Cultural Expression and Local Content

The global internet is rich and diverse, but it can also overshadow local voices. Large platforms tend to amplify content that appeals to broad audiences, often at the expense of regional languages, traditions, and perspectives.

Mesh networks create space for local content to flourish. Because they are rooted in specific communities, they naturally reflect local culture. People can share stories, music, educational materials, and news relevant to their lives, without competing for attention on global platforms.

This local focus can strengthen cultural identity and preserve knowledge that might otherwise be lost. In some cases, mesh networks have been used to support indigenous languages, community archives, and local media, providing a digital home for cultural expression.

Legal and Regulatory Challenges

Building a community mesh network does not happen in a vacuum. It intersects with legal and regulatory frameworks that govern spectrum use, telecommunications, and internet services. In some regions, regulations make it difficult or even illegal to operate independent networks.

Spectrum, the range of frequencies used for wireless communication, is often tightly controlled. While unlicensed bands exist and are commonly used for mesh networking, power limits and other restrictions can constrain network design. Navigating these rules requires technical knowledge and sometimes legal advocacy.

There are also questions about liability and responsibility. Who is accountable if something goes wrong on a community network? How are disputes resolved? These issues highlight the need for supportive policies that recognize the legitimacy and value of community-built infrastructure.

The Global Landscape of Mesh Networks

Around the world, mesh networks have taken many forms, shaped by local conditions and needs. In dense urban neighborhoods, networks may rely on rooftop antennas and short-range wireless links. In rural areas, they may span long distances, connecting villages across challenging terrain.

Despite these differences, common themes emerge. Mesh networks often arise where traditional infrastructure is lacking or inadequate. They are driven by local initiative rather than external investment. They blend technical innovation with social organization.

These networks demonstrate that connectivity is not a binary state but a spectrum. Even limited, local communication can have immense value, supporting education, commerce, and social cohesion. By starting small and growing organically, mesh networks adapt to their environments in ways centralized systems often cannot.

Mesh Networks and the Philosophy of the Internet

At a deeper level, mesh networks invite us to reconsider what the internet is and what it could be. The original vision of the internet emphasized decentralization, resilience, and openness. Over time, economic and political forces have reshaped that vision, concentrating power and influence.

Mesh networks revive the idea that the internet can be a commons, a shared space built and governed by its users. They challenge the notion that connectivity must be mediated by large institutions. Instead, they suggest that collaboration and mutual aid can form the basis of digital infrastructure.

This philosophy resonates with broader movements toward decentralization, from renewable energy cooperatives to open-source software. It reflects a desire to align technology with human values rather than treating it as an external force.

Technical Limits and Realistic Expectations

While mesh networks are powerful, they are not a panacea. They face technical limits related to bandwidth, latency, and scalability. Wireless links are subject to interference and environmental factors. Managing large networks can become complex as the number of nodes grows.

These challenges require realistic expectations and thoughtful design. Mesh networks are best seen as complementary to, rather than replacements for, traditional infrastructure. They excel in specific contexts, particularly where resilience, local control, and affordability are priorities.

Ongoing research and development continue to improve mesh networking technologies. Advances in hardware efficiency, routing algorithms, and spectrum management expand what is possible. As technology evolves, the boundary between community networks and mainstream infrastructure may blur.

The Human Story Behind the Technology

What makes mesh networks truly compelling is not the technology itself but the human stories they contain. They are stories of neighbors climbing rooftops to install antennas, of volunteers teaching workshops, of communities refusing to accept isolation as inevitable.

These stories reveal a fundamental truth: the internet is not just cables and code but a social system shaped by human choices. Mesh networks make that reality visible. They remind us that connectivity is something we can co-create, grounded in relationships and shared purpose.

In building their own internet, communities rediscover an ancient practice in a modern form: working together to meet common needs. The network becomes a mirror of the community, reflecting its strengths, challenges, and aspirations.

The Future of Community-Built Internet

As the world becomes increasingly connected, the question is not whether the internet will continue to grow, but how. Will it become more centralized, more controlled, and more opaque? Or will it evolve toward greater participation and resilience?

Mesh networks offer one possible path forward. They demonstrate that alternative models are not only imaginable but achievable. They show that technology can empower rather than dominate, connect rather than divide.

The future of mesh networking will depend on many factors, including technological innovation, regulatory environments, and social will. But its deeper significance lies in the example it sets. It reminds us that the internet, like any human creation, reflects our values.

Conclusion: Reclaiming the Internet Together

Mesh networks are more than a technical solution to connectivity problems. They are an expression of collective imagination and determination. They show that communities need not wait passively for access to be granted from above. Instead, they can build, maintain, and govern their own digital spaces.

In a world where connectivity increasingly shapes opportunity, culture, and power, this possibility matters deeply. Mesh networks return the internet to its roots as a decentralized, resilient, and human-centered system. They invite us to see technology not as a distant force but as a shared endeavor.

By building their own internet, communities do something quietly revolutionary. They assert that connection is a right, not a privilege, and that the networks binding us together are strongest when they are woven by many hands.