Personality has always fascinated human beings. Why do some people thrive in social settings while others prefer solitude? Why do some recharge in the company of others while some feel drained after interaction? The differences between introversion and extroversion lie at the heart of personality psychology. These two personality orientations—introversion and extroversion—describe fundamental differences in how individuals gain energy, process information, and engage with the world around them.

The concept of introversion and extroversion is more than just a popular cultural label—it is a scientifically studied psychological dimension that has evolved over a century of research. From Carl Jung’s pioneering theories in the early 20th century to the modern neuroscience of personality, the introvert-extrovert spectrum continues to shape how psychologists understand human behavior, emotion, and cognition.

This article explores what psychology research truly means by introversion and extroversion, how these traits are defined and measured, their neurological and biological foundations, their social and emotional differences, and how modern research challenges the oversimplified myths surrounding them.

The Historical Origins of Introversion and Extroversion

The terms introversion and extroversion originated from Swiss psychiatrist Carl Gustav Jung, who introduced them in his 1921 book Psychological Types. Jung proposed that people differ in how they direct and receive energy. Extroverts, he argued, direct their energy outward toward people and activities, while introverts turn their energy inward toward ideas and reflections.

For Jung, introversion and extroversion were not mutually exclusive categories but opposite poles of a spectrum. Everyone has both tendencies to some degree, but one typically dominates. Jung’s theory was revolutionary because it reframed personality not as fixed or moral but as a natural and neutral variation in human orientation toward the world.

His ideas influenced later personality theories, including the famous Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI), which uses Jung’s concepts to categorize individuals into 16 personality types based on their introverted or extroverted preference and other dimensions such as thinking versus feeling, and sensing versus intuition. Although MBTI is widely used in organizational and educational settings, it is often criticized for lacking scientific rigor compared to modern psychometric models.

Nonetheless, Jung’s basic insight—that introversion and extroversion represent core differences in attention, motivation, and energy—laid the foundation for decades of psychological research that followed.

Defining Introversion and Extroversion in Modern Psychology

Modern psychology defines introversion and extroversion not as absolute categories but as continuous traits that vary among individuals. Most people fall somewhere between the two extremes—a middle group known as ambiverts.

In contemporary research, these traits are part of the Big Five Personality Model, one of the most widely accepted frameworks in psychology. In this model, Extraversion is one of the five broad dimensions of personality, alongside Neuroticism, Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, and Openness to Experience.

Within this framework, extraversion is characterized by qualities such as sociability, assertiveness, excitement-seeking, talkativeness, and positive emotionality. Introversion, on the other hand, is defined by lower levels of those traits, coupled with a preference for quiet environments, solitary activities, and deeper social connections rather than broad social networks. Importantly, introversion is not the same as shyness or social anxiety. Shyness involves fear or discomfort in social situations, whereas introversion reflects a natural preference for low-stimulation environments and inward focus.

In short, extraverts draw energy from social interaction and external stimulation, while introverts recharge through solitude and internal reflection.

The Biological and Neurological Basis of Personality

One of the most significant advances in psychology has been the exploration of the biological underpinnings of introversion and extroversion. Research in neuroscience and psychophysiology suggests that these traits are deeply rooted in the brain’s structure and chemistry.

Studies have shown that extraversion is associated with higher levels of activity in brain regions linked to reward processing, particularly the dopamine system. Dopamine is a neurotransmitter involved in motivation, pleasure, and learning from rewards. Extroverts tend to have more sensitive dopamine pathways, which makes them more responsive to external rewards like social interaction, excitement, and novelty. This heightened sensitivity encourages them to seek out stimulating environments.

Introverts, by contrast, have less reactive dopamine systems, meaning they are less driven by external stimulation. Instead, they may rely more on the neurotransmitter acetylcholine, which is linked to introspection, long-term focus, and calm alertness. As a result, introverts often find satisfaction in quiet reflection, deep thought, and meaningful one-on-one interactions rather than crowds or loud environments.

Functional brain imaging also reveals structural and functional differences. Introverts tend to exhibit greater activity in the prefrontal cortex, an area associated with planning, decision-making, and abstract thinking, while extroverts show stronger activity in regions linked to sensory processing and reward anticipation.

These biological patterns suggest that introversion and extroversion are not merely behavioral preferences—they are neurobiological dispositions that influence how individuals experience and process the world.

The Energy Theory of Personality

Jung’s original theory that introverts and extroverts differ in their “psychic energy” has been refined in modern terms as the arousal theory of personality. According to this theory, people differ in their baseline level of cortical arousal—essentially, how alert and stimulated their brain is at rest.

Introverts generally have higher baseline cortical arousal, meaning their brains are naturally more active even in calm conditions. Therefore, additional external stimulation can easily lead to overstimulation and fatigue. This explains why introverts often prefer quieter environments and need time alone to “recharge.”

Extroverts, in contrast, have lower baseline arousal levels. They seek external stimulation to raise their arousal to an optimal level, which makes them drawn to social activities, lively environments, and new experiences. The British psychologist Hans Eysenck was among the first to formalize this idea in the 1950s, proposing that differences in cortical arousal explain why some individuals are naturally more outgoing while others are more reserved.

This theory has been supported by physiological studies showing that introverts tend to exhibit stronger responses to sensory stimulation, such as loud sounds or bright lights, and may experience greater fatigue after prolonged social interaction. Extroverts, however, may feel bored or restless when deprived of stimulation.

Emotional and Cognitive Differences

Research also shows that introverts and extroverts differ in their emotional processing and cognitive styles. Extroverts are generally more likely to experience positive emotions and exhibit higher baseline happiness. This does not necessarily mean introverts are unhappy; rather, extroverts show greater responsiveness to rewarding stimuli, while introverts are more sensitive to potential threats and subtler emotional cues.

Extroverts often display higher levels of positive affectivity, meaning they are more cheerful, optimistic, and enthusiastic. They also tend to use more outward-focused coping strategies, such as seeking social support when dealing with stress. Introverts, on the other hand, may rely more on inward strategies, such as reflection, problem-solving, or avoidance.

Cognitively, introverts often excel in tasks requiring sustained attention, deep concentration, and long-term memory, whereas extroverts perform better in tasks involving rapid decision-making, multitasking, and interaction. These patterns are consistent with the idea that introverts prefer depth while extroverts prefer breadth of experience.

Social Behavior and Relationships

One of the clearest distinctions between introverts and extroverts lies in how they relate to others. Extroverts are energized by social interaction. They often enjoy large groups, social gatherings, and collaborative environments. Their enthusiasm and sociability make them skilled at initiating conversations, networking, and engaging with strangers.

Introverts, by contrast, may find such settings draining and prefer smaller, more intimate interactions. They are more likely to build deep, long-lasting relationships with a few close friends rather than maintain a wide circle of acquaintances. Their communication style tends to be reflective and thoughtful; they may take longer to speak but often express themselves with precision and insight.

Contrary to stereotypes, introverts are not necessarily antisocial. They simply socialize differently. Research shows that introverts value meaningful connections and may invest more emotionally in relationships, whereas extroverts often enjoy the social experience itself, regardless of depth.

Interestingly, studies suggest that both personality types can complement each other in relationships. Introverts can offer emotional depth and empathy, while extroverts bring enthusiasm and energy. Successful relationships often depend on mutual understanding and respect for each other’s social needs.

Work, Creativity, and Career Patterns

Personality type influences not only how individuals interact socially but also how they work and create. Extroverts often excel in dynamic, fast-paced environments that require teamwork, persuasion, and assertiveness—such as sales, management, teaching, and public relations. Their ability to adapt quickly and maintain high energy levels makes them effective leaders and communicators.

Introverts, on the other hand, thrive in environments that allow for autonomy, focus, and depth of thought—such as research, writing, programming, design, and academia. Their reflective nature and ability to sustain concentration make them excellent problem-solvers, analysts, and creators.

Creativity is an area where introverts often shine. Studies by psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi and others show that creative individuals frequently display introverted tendencies, as creativity requires long periods of solitude, introspection, and independent thinking. However, extroverts can also be creative, particularly in collaborative or improvisational settings such as music, theater, or team-based innovation.

Ultimately, both personality types can succeed across all fields. The key lies in understanding one’s energy patterns and creating an environment that supports them.

Misconceptions and Cultural Bias

Modern psychology has worked to debunk many myths about introversion and extroversion. One common misconception is that extroverts are happier or more successful. While extroverts do report higher average levels of positive affect, this does not translate to greater life satisfaction for everyone. Research shows that happiness depends on congruence between personality and lifestyle. An introvert forced into constant social activity may feel exhausted and unhappy, just as an extrovert confined to solitude may feel bored and restless.

Another misconception is that introverts are shy or socially anxious. In reality, shyness is linked to fear of social judgment, while introversion is about energy preference. Many introverts enjoy socializing but simply need time to recharge afterward. Similarly, extroverts are not inherently shallow or attention-seeking; their social orientation is biologically and psychologically natural.

Cultural factors also play a major role in shaping perceptions. Western societies, particularly the United States, often idealize extroversion—valuing assertiveness, sociability, and public confidence. Eastern cultures, by contrast, tend to value introverted qualities such as humility, self-restraint, and thoughtfulness. These cultural norms influence how individuals express their personality and how it is perceived by others.

The Science of the Ambivert

While the introvert-extrovert distinction is widely known, many people actually fall in the middle of the spectrum. Psychologists refer to them as ambiverts. Ambiverts display a balance of introverted and extroverted traits, adapting their behavior depending on context.

Research by organizational psychologist Adam Grant suggests that ambiverts may have certain advantages in social and professional settings. They are flexible, capable of engaging with others while also knowing when to listen and reflect. In sales and leadership roles, ambiverts often outperform both extreme introverts and extroverts, as they can modulate their energy and communication style effectively.

The existence of ambiverts reinforces the idea that personality is not binary but fluid. Most people are not entirely one or the other but exhibit a dynamic mix of both traits depending on mood, environment, and task.

Psychological Well-Being and Mental Health

Personality influences not only how we interact and work but also how we experience emotional well-being. Studies suggest that extraversion is positively correlated with subjective happiness and social engagement, while introversion is associated with deeper emotional awareness and sensitivity. However, neither orientation guarantees or prevents psychological health.

Introverts may be more prone to internalizing disorders such as depression or anxiety, particularly if their need for solitude is misunderstood or stigmatized. Extroverts, conversely, may be more vulnerable to impulsivity, risk-taking, or substance abuse. Mental well-being depends not on personality type but on balance, self-awareness, and alignment between personality and lifestyle.

Both introverts and extroverts can cultivate well-being by respecting their natural tendencies. Introverts benefit from quiet reflection, creative expression, and meaningful social bonds. Extroverts thrive on social interaction, teamwork, and physical activity. Recognizing and honoring these differences helps individuals build resilience and authenticity.

Modern Neuroscience and Personality Research

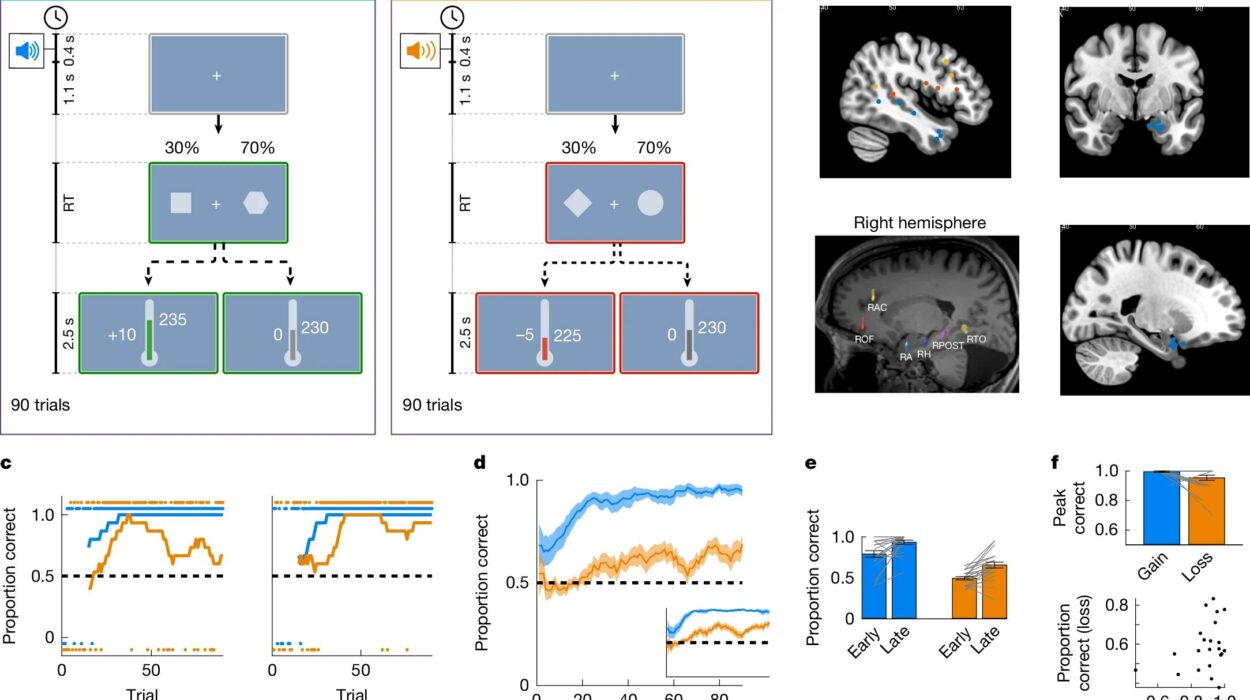

Recent advances in neuroscience have allowed scientists to study introversion and extroversion at an unprecedented level of detail. Using techniques such as fMRI and EEG, researchers have identified specific brain networks involved in social behavior, motivation, and reward processing.

For example, studies show that extroverts exhibit stronger responses in the ventral striatum and orbitofrontal cortex when anticipating positive outcomes. These regions are central to the brain’s reward system, explaining extroverts’ greater pursuit of stimulation and novelty. Introverts, on the other hand, show heightened activity in the prefrontal cortex and insula, which are associated with internal processing, emotional regulation, and self-awareness.

Furthermore, genetic studies indicate that traits of introversion and extroversion are moderately heritable, with estimates suggesting that 40% to 60% of the variation in extraversion may be linked to genetic factors. However, environment, upbringing, and cultural context also play crucial roles in shaping how these traits manifest.

Neuroscientists are also exploring the role of brain connectivity. Introverts may have more robust long-range neural connections, supporting deep and sustained thinking, while extroverts exhibit more localized connections favoring quick, reactive processing. These findings highlight how personality reflects the dynamic organization of the brain itself.

Personality Across the Lifespan

Personality traits, including introversion and extroversion, are relatively stable but can evolve over time. Research in developmental psychology shows that children often display early signs of these traits—some are naturally outgoing and active, while others are reserved and observant.

As people age, however, their levels of extraversion may shift. Adolescence and early adulthood tend to be more extraverted periods due to social exploration and career building. Middle and older adulthood often bring greater emotional stability and introspection, leading some individuals to become more introverted over time.

Life experiences, relationships, and career demands also shape personality expression. A naturally introverted person can learn extroverted behaviors when necessary, just as an extrovert can cultivate solitude and mindfulness. Personality is best seen as a flexible framework rather than a fixed destiny.

The Balance of Opposites

In Jungian psychology, introversion and extroversion represent complementary forces rather than opposing ones. A psychologically healthy person integrates both aspects, knowing when to turn inward and when to engage outwardly. Balance is key.

Excessive extroversion without introspection can lead to superficiality, impulsiveness, or dependency on external validation. Excessive introversion without engagement can lead to isolation, overthinking, or detachment. True psychological maturity involves developing the less dominant side of one’s personality while remaining authentic to one’s nature.

In this sense, the introvert-extrovert dynamic is not about labels but about harmony. Just as night complements day, both orientations are essential aspects of human diversity and evolution.

The Role of Culture, Technology, and the Modern World

The digital age has reshaped how introverts and extroverts interact with the world. Social media, virtual communication, and online communities offer introverts new ways to express themselves without the overstimulation of face-to-face interaction. Extroverts, meanwhile, thrive in digital networking and collaborative platforms that allow constant social connection.

However, technology also blurs boundaries, sometimes forcing introverts into constant exposure or encouraging extroverts to overextend themselves. Psychologists note the importance of mindful digital use that aligns with one’s temperament—introverts may benefit from scheduled solitude, while extroverts may need in-person interaction to avoid emotional disconnection.

Culturally, awareness of introversion has grown. Books such as Quiet by Susan Cain have helped reframe introversion as a strength rather than a flaw, emphasizing the value of depth, sensitivity, and reflection in leadership and creativity. The modern world increasingly recognizes that innovation requires both the extrovert’s boldness and the introvert’s contemplation.

The Psychology of Energy and Meaning

At a deeper psychological level, introversion and extroversion reflect two different modes of meaning-making. Extroverts find fulfillment in engagement—with people, experiences, and action. Their energy moves outward, toward the external world. Introverts find meaning in reflection, imagination, and internal coherence. Their energy moves inward, toward the inner world of thought and feeling.

Neither mode is superior; both are essential to human progress. Civilization advances through the interplay of thinkers and doers, reflectors and connectors. Science, art, philosophy, and politics all thrive on this balance. Extroverts propel movement and collaboration, while introverts provide insight, analysis, and depth.

Toward an Integrated Understanding

Contemporary psychology increasingly emphasizes an integrative view of personality. Rather than dividing people into fixed categories, researchers focus on flexibility, context, and individual differences. People can express different aspects of their personality depending on situation, mood, and goals.

This adaptive capacity—known as trait elasticity—means that personality is both stable and responsive. An introvert can act extroverted when giving a presentation, while an extrovert can be reflective when solving a complex problem. The healthiest individuals are those who can shift fluidly along the spectrum while remaining anchored in their authentic self.

Conclusion

The distinction between introvert and extrovert remains one of the most enduring concepts in psychology. From Jung’s early theories to modern neuroscience, it continues to offer profound insight into human behavior, motivation, and social connection. Introversion and extroversion are not opposing boxes but complementary dimensions of personality, each with unique strengths, challenges, and values.

Understanding these orientations allows us to appreciate the diversity of human nature and to create environments where all types can thrive. The world needs the extrovert’s enthusiasm as much as the introvert’s wisdom, the social spark as much as the quiet depth.

Psychology teaches that balance—not conformity—is the key. Whether one’s energy flows inward or outward, every person contributes to the intricate mosaic of human experience. In the harmony of both introverted reflection and extroverted expression lies the true richness of the human mind.