Under the cobalt skies of central Utah, amid the dry mountains and the whisper of wind through trembling leaves, stands an ordinary-looking forest. The trunks shimmer pale white, marked by black scars and horizontal striations. Heart-shaped leaves quake and flutter with the faintest breath, creating a sound like rain falling on silk.

Yet this is no ordinary grove. The thousands of aspen trunks, stretching across more than a hundred acres, belong not to separate trees—but to one single organism. Beneath the soil, they are connected by a single, sprawling root system, sharing the same genetic code. This shimmering sea of leaves is Pando—the Trembling Giant—an ancient living entity that scientists believe may be as old as 80,000 years. Some estimates even suggest it could be older still.

When one stands beneath its leaves, it’s easy to forget that you are standing inside a creature older than civilization itself. The Persians had not built Persepolis. Humans had not painted Lascaux’s caves. Woolly mammoths still roamed the plains. Yet Pando was already alive, sending up new shoots from its roots, quietly surviving the glacial ages.

Inside this forest beats the hidden pulse of one of Earth’s oldest, most massive living organisms—a survivor, a shape-shifter, and a fragile elder on the brink of crisis.

A Secret Life Underground

From the surface, Pando appears as a typical aspen stand. Its trunks stand slender and smooth, clothed in bark that peels like parchment. Each stem grows for about 80 to 100 years, then dies, only to be replaced by new shoots springing from the underground network.

Aspens are masters of regeneration. Unlike oak or pine, they don’t rely primarily on seeds. Instead, they reproduce clonally. When a tree dies or suffers injury, hormones signal the roots to push up new stems. Each shoot is genetically identical to its siblings, forming a colony—a single organism in countless vertical fragments.

Beneath Pando, a hidden network of roots weaves through the soil, some descending several meters deep, others spreading outward over vast distances. The roots communicate chemically, sending signals of stress, drought, or insect attack. Pando is not merely a grove—it’s a colossal underground brain, responding to threats as one.

Some scientists compare the colony to a coral reef, where individual polyps form a collective creature. Others liken it to a superorganism, like an ant colony. But Pando is even more intimately fused. Its trunks are not separate individuals—they are organs of a single body, all driven by the same DNA.

This life underground is why Pando has endured for so many millennia. Fires might scorch its surface. Insects might strip leaves. But so long as the roots live, Pando survives. New trunks will emerge, phoenix-like, from the ashes.

The Age Mystery

Determining Pando’s age has proven both fascinating and elusive. Tree-ring counts are useless for estimating the colony’s true age, because no single stem lasts more than about a century or two. Instead, scientists estimate age through genetic sampling and studying rates of expansion.

Pando covers approximately 106 acres in Fishlake National Forest, with an estimated weight exceeding 6,600 metric tons. It’s often called the heaviest living organism on Earth, outweighing even the largest whales.

But when did it begin?

Estimates range widely. Genetic uniformity suggests that Pando has been expanding for tens of thousands of years. Some researchers calculate its age based on how far the clone has spread, considering factors like soil conditions, climate, and growth rates. One often-cited figure suggests Pando may be around 80,000 years old, dating back to the last Ice Age.

Yet other scientists propose more conservative ages—perhaps 10,000 to 14,000 years—arguing that Pando couldn’t have survived beneath massive glaciers that once covered parts of Utah. If it’s younger, it still ranks among Earth’s eldest living things, older than the pyramids, older than writing itself.

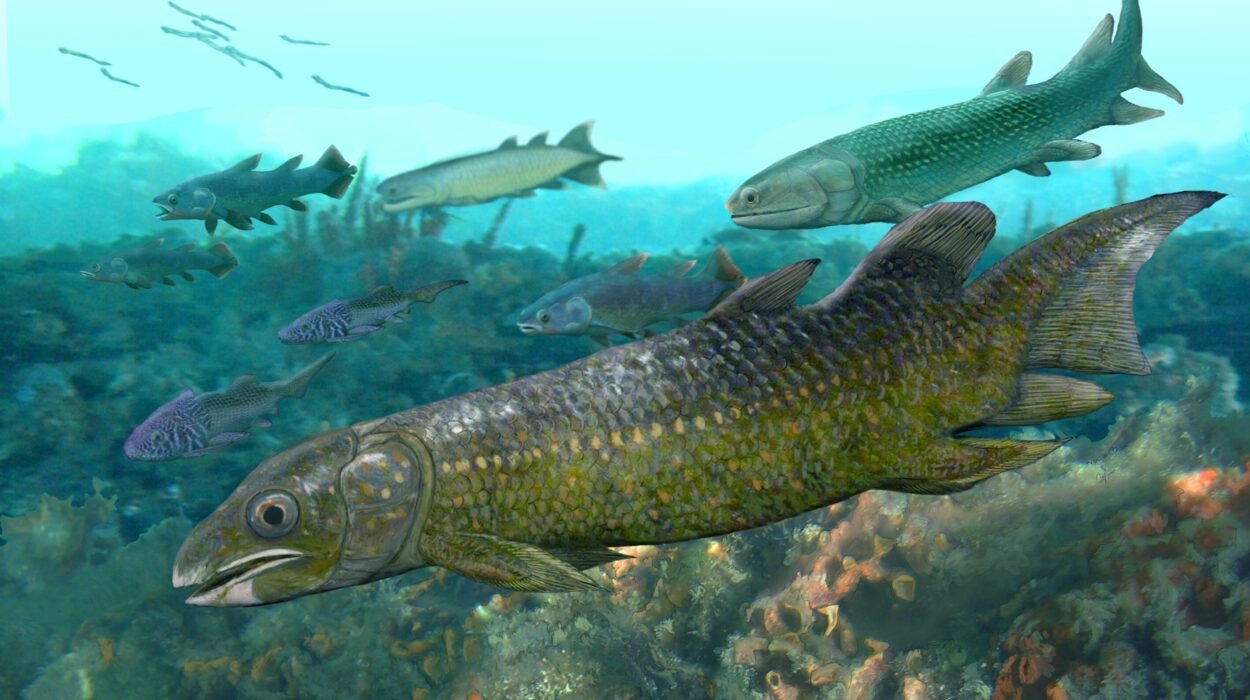

But suppose Pando is indeed 80,000 years old. That would place its origin at the dawn of the Upper Paleolithic. Humans were first carving figurines from mammoth ivory. The Sahara was green. And in the American West, the climate was cooler, shaped by glacial winds.

Either way, Pando is a silent witness to almost unimaginable spans of time.

Seasons of Survival

Throughout the millennia, Pando has endured droughts, fires, grazing animals, pest invasions, and dramatic climate shifts. Each time, it adapted.

Fire, once a threat, also became a savior. In healthy aspen ecosystems, periodic wildfires clear away older trees and stimulate root systems to send up vigorous new shoots. Pando, hidden safely beneath the flames, would rebound in waves of fresh growth.

In times of severe drought, Pando slows its metabolism. Aspen roots can store water and carbohydrates, sustaining the colony through lean years. Its root system functions as a reserve bank, rationing resources when the weather turns cruel.

Animals have long been both Pando’s partners and enemies. Elk and deer feed on tender young shoots, sometimes shaping the forest’s growth. Historically, predators like wolves helped keep grazers in check, preserving a balance. But modern changes have upset that fragile equilibrium.

Pando’s survival story is not simply resilience. It’s a record of symbiosis—a living chronicle of cooperation and competition, fire and ice, feast and famine.

The Genetic Signature

One of the marvels of Pando is its astonishing genetic stability. All 47,000 or so stems share essentially the same genome. Genetic testing has confirmed that Pando is a single male clone. (Yes—Pando is technically a male organism, producing only male flowers.)

Scientists have found slight genetic variations between some parts of the colony, likely the result of somatic mutations—random changes as cells divide over thousands of years. Yet these differences are minor. Pando’s DNA remains remarkably unchanged across tens of thousands of stems and countless centuries.

This genetic uniformity is a strength but also a vulnerability. Pando lacks genetic diversity, making it more susceptible to disease or environmental shifts. A pathogen perfectly adapted to exploit one stem’s DNA could devastate the entire clone.

It’s one of the paradoxes of clonal life: while it offers extraordinary longevity, it can become an evolutionary trap.

The Threats Aboveground

For thousands of years, Pando faced natural challenges—fire, grazing, insects. But recent decades have brought new threats of human origin.

One of the greatest is overbrowsing. Modern predator declines have allowed populations of mule deer and elk to swell. Without wolves and mountain lions keeping them in check, these herbivores devour Pando’s young shoots as quickly as they emerge. The result is an aging forest, with few new trunks rising to replace the old.

Fence studies have revealed stark contrasts: protected areas burst with young saplings, while unfenced zones remain bare, the soil trampled and lifeless. Without intervention, large parts of Pando may “senesce”—age into decline without new growth.

Other dangers loom. Climate change brings more intense droughts, stressing aspen roots. Invasive species and pathogens threaten the health of trees already weakened by environmental stress. Human development fragments habitats, disrupting the intricate balance of forest life.

Scientists studying Pando describe it as a patient in critical care. Parts of the clone are stable or recovering. Others show signs of severe decline.

The world’s oldest organism stands at the brink of an uncertain future.

The Ecological Giant

Yet Pando is not merely a botanical curiosity. It’s an ecosystem engine.

Aspen groves are biodiversity hotspots. Beneath Pando’s trembling canopy thrive hundreds of plant species, including wildflowers, grasses, and shrubs that would vanish in denser conifer forests. Aspen stands also provide habitat for birds, insects, mammals, and fungi.

Pando’s leaf litter feeds the soil, enriching it with nutrients. Its deep roots prevent erosion, anchoring soil on steep slopes. Aspen trees absorb large quantities of carbon dioxide, helping regulate the planet’s climate.

In autumn, Pando becomes a riot of gold, its leaves glowing like molten sunlight against the dark evergreen slopes. Wildlife congregates in its shelter. Hunters, hikers, and photographers stand awed beneath its canopies, often unaware they’re witnessing the world’s oldest lifeform.

Without Pando, entire communities of life would vanish.

A Symbol of Conservation

Recognizing Pando’s significance, scientists, conservationists, and the U.S. Forest Service have launched efforts to protect it. Experiments with fencing and managed grazing show promise. Some areas are rebounding dramatically once protected from deer and elk.

Yet preserving Pando is not a simple task. It requires addressing broader ecological imbalances—restoring predator populations, managing human impacts, and preparing for a warming climate.

Pando has become an emblem of conservation. Its story resonates deeply because it embodies both endurance and fragility. It has survived ice ages, fires, and storms, only to face peril from the modern human footprint.

Scientists warn that losing Pando would mean more than losing a genetic marvel. It would erase a living connection to Earth’s deep past—a biological time capsule stretching back to the Pleistocene.

The Poetic Giant

Beneath its scientific importance, Pando is also a creature of poetry. To stand within it is to feel a sense of time so vast it defies comprehension.

Consider what Pando has seen. While it rooted itself in the soil of prehistoric Utah, the continents shifted imperceptibly beneath its roots. Great ice sheets waxed and waned. Saber-toothed cats prowled the valleys. Indigenous peoples arrived, living lightly among the trees. Civilizations rose and fell. Modern humans built cities, split the atom, sent spacecraft beyond the solar system.

Through it all, Pando stood quiet vigil, trembling in the breeze.

Walking among its white trunks, one feels whispers of eternity. Each stem is both ephemeral and eternal—a leaf of a single giant, living organism. It’s a paradox: the colony is ancient, yet its stems are perpetually young. Pando is immortal in essence, yet mortal in parts.

No photograph or statistic captures its essence fully. Pando must be felt—the cool shade, the flicker of gold leaves, the scent of damp earth, the hush that settles between rustling breezes.

The Future of an Ancient Being

As scientists work to save Pando, questions loom. How do we preserve a being that evolved under natural cycles of fire, predators, and shifting climates? How do we protect it in an age of fences, highways, and climate disruption?

Some researchers suggest controlled burns to simulate the fires that once rejuvenated the forest. Others advocate for predator reintroduction. Some propose reducing deer populations through managed hunts.

There is no single answer. Pando’s future hinges on complex interactions among humans, wildlife, climate, and the forest itself.

Yet there is hope. The same resilience that carried Pando through the Ice Age may still help it survive. Clonal colonies can lie dormant underground for centuries, waiting for conditions to improve. Even if large portions die back, the roots may persist, poised to send up new shoots in better times.

Pando reminds us that the natural world can endure astonishing trials—but only if given a chance.

A Living Testament

In the end, Pando is more than a scientific marvel. It’s a symbol of life’s astonishing continuity and adaptability. It reminds us that the Earth’s oldest beings are not dinosaurs entombed in stone but living neighbors rooted in our landscapes.

Its trembling leaves speak softly of time, patience, and hidden strength. It teaches humility, urging us to consider that our human lifespans are mere flickers compared to its reign.

To save Pando is to preserve a living bridge across time—a silent witness to all humanity’s triumphs and follies. It is a reminder that the world’s oldest organisms are not relics of the past but living participants in our shared present.

As the sun sets over Fishlake National Forest, shadows deepen beneath Pando’s canopy. The leaves whisper secrets in the wind. And beneath the soil, the Trembling Giant dreams on—a single vast organism, older than empires, older than memory, yearning quietly for its next thousand years.