We wake up, open our eyes, stretch, feel hunger, speak words, remember names, make decisions, fall in love, lose our tempers, laugh at jokes, and mourn our losses—all because of one organ that weighs about three pounds and resembles an oddly folded lump of grey and white tissue. The brain, tucked safely within the cranium, silently governs the vast symphony of human behavior. Yet, most of us go our entire lives without truly understanding how it does so. What is it about this tangled mass of neurons and chemicals that shapes who we are, how we think, what we feel, and how we act?

Behavior does not emerge from thin air. Every impulse, every reaction, every dream or fear we harbor is rooted in biological processes. And at the very center of it all sits the brain—not simply as a cold, mechanical calculator of thoughts, but as a living, ever-changing ecosystem shaped by evolution, molded by experience, and fueled by electrical storms and chemical whispers. Understanding how the brain influences behavior means unlocking the door to who we truly are.

A Brief Evolution of the Human Brain

The human brain did not appear overnight. It is the product of millions of years of evolutionary refinement. The earliest vertebrates had basic neural circuits that helped them respond to light, heat, and movement. Over time, brains became more complex, layering new functions atop older ones.

At the base lies the brainstem, responsible for basic survival: breathing, heart rate, and arousal. Sitting above it is the limbic system, often called the “emotional brain,” which evolved to help animals respond to rewards and dangers. The crowning jewel of evolution is the neocortex, particularly the prefrontal cortex, which in humans is remarkably developed. This region enables us to think abstractly, plan for the future, reflect on the past, and imagine things that do not exist. It is the foundation of art, philosophy, science, morality, and culture.

Behavioral influence begins with this evolutionary hierarchy. When we act impulsively or emotionally, we are often engaging older, deeper structures. When we reflect and reason, we are engaging newer, more complex areas. The brain isn’t a unified commander—it’s a committee of regions, each with its own voice, often pulling us in different directions.

Neurons: The Messengers of Thought and Action

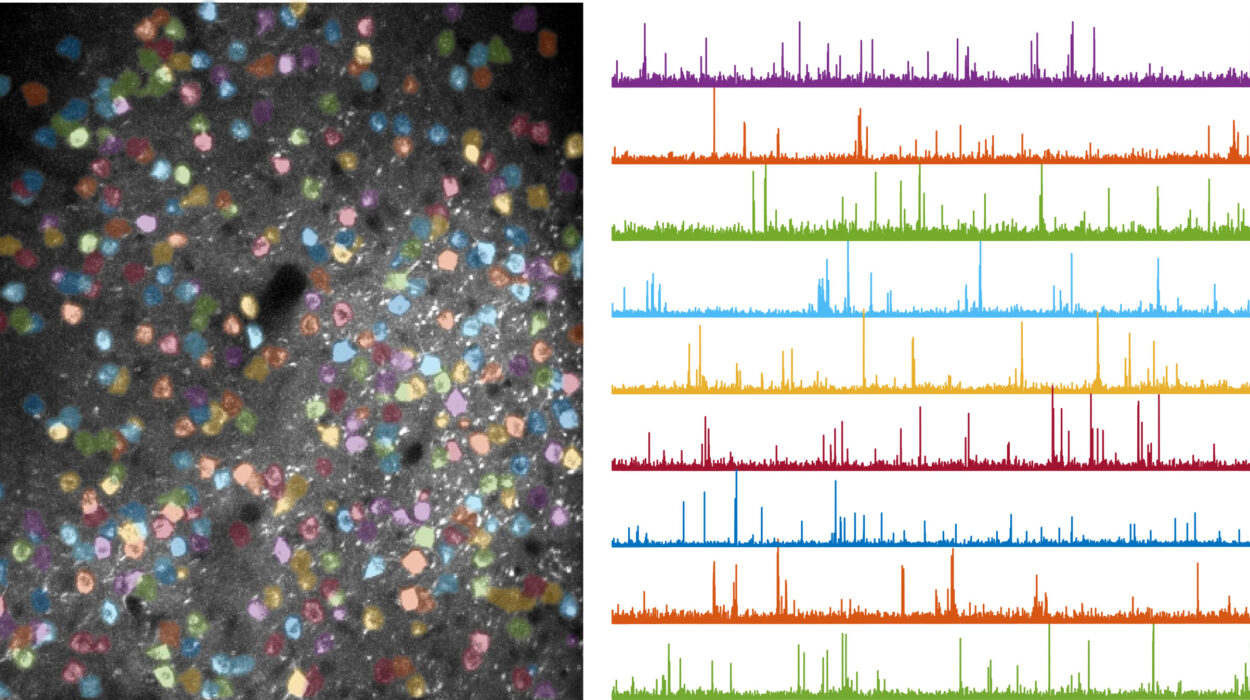

At the heart of the brain’s influence on behavior are neurons—billions of them, connected by trillions of synapses. Each neuron is a tiny factory of communication, sending and receiving electrical and chemical signals at astonishing speed. They form networks that process specific kinds of information. Visual experiences are processed in the occipital lobe, language in Broca’s and Wernicke’s areas, memory in the hippocampus, and emotion in the amygdala.

What we call “thought” is really a pattern of firing neurons. When you recognize a face, remember a song, or choose between pizza and pasta, thousands or millions of neurons activate in synchronized patterns. They don’t operate in isolation; instead, they form circuits—recurrent loops of information that can be strengthened or weakened over time.

This is where learning comes in. Each time we repeat a behavior or thought, we strengthen the neural pathways involved. “Neurons that fire together wire together,” goes the popular saying in neuroscience. Over time, our behaviors become habits, our thoughts become beliefs, and our emotions become reflexes—because the brain reshapes itself through experience.

Neurotransmitters and the Chemistry of Emotion

Electricity carries the message down a neuron, but chemicals carry it across the gap between neurons. These chemicals, called neurotransmitters, are the molecular messengers of behavior. Different neurotransmitters have different effects, and their balance or imbalance can drastically alter how we feel and act.

Dopamine, for example, is deeply tied to motivation, reward, and pleasure. When we anticipate something good—a delicious meal, a romantic encounter, a victory in a video game—dopamine surges, reinforcing the behavior that led to it. This is the same system exploited by addictive substances and behaviors, which hijack the brain’s natural reward circuitry.

Serotonin, often linked to mood, affects how we feel emotionally. Low levels are associated with depression and anxiety. Norepinephrine influences alertness and arousal. Oxytocin and vasopressin are involved in bonding and trust. Endorphins reduce pain and increase pleasure.

Even subtle shifts in these chemicals can change behavior profoundly. A depressed person may not lack willpower—they may lack serotonin. An anxious person may have an overactive norepinephrine system. Neurochemistry doesn’t excuse behavior, but it deeply contextualizes it. Our brains don’t simply reflect the world—they chemically react to it.

The Brain Under Stress: Behavior on the Edge

Imagine standing face-to-face with a predator. Your heart races, your pupils dilate, your muscles tense, and your thoughts narrow. This ancient “fight or flight” response is orchestrated by the brain, particularly the amygdala and hypothalamus. The adrenal glands flood your bloodstream with cortisol and adrenaline, preparing you to survive. But modern life has no saber-toothed tigers. Instead, our threats are emails, deadlines, bills, and social rejection.

Chronic stress alters brain behavior in subtle but powerful ways. The prefrontal cortex, which governs rational thought, becomes less effective under stress. Meanwhile, the amygdala becomes hyperactive, making us more prone to emotional reactions, anxiety, and fear. Long-term stress can even shrink the hippocampus, impairing memory and learning.

People under chronic stress behave differently not because they choose to, but because their brains are functioning differently. They may become irritable, distracted, forgetful, or withdrawn. The brain does not distinguish between physical danger and psychological threat. Its response is primitive, automatic, and difficult to override.

The Social Brain: Wired for Connection

We are not solitary creatures. Human survival has always depended on groups. As a result, the brain has evolved intricate mechanisms for interpreting social cues, building relationships, and forming communities.

The mirror neuron system allows us to intuitively understand others’ emotions by simulating them in our own brains. When you see someone smile, your brain activates as if you were smiling too. When you see someone in pain, similar regions light up as when you experience pain. This neural empathy forms the basis of compassion and morality.

The prefrontal cortex plays a key role in perspective-taking, or “theory of mind”—our ability to imagine what someone else is thinking or feeling. This allows for complex behaviors like deception, cooperation, and storytelling. The brain’s default mode network, active when we daydream or reflect, is also deeply involved in self and social understanding.

Humans have evolved to read faces, voices, and body language with incredible precision. This is why tone of voice or a subtle expression can dramatically influence behavior. Loneliness, social rejection, and isolation are not just unpleasant—they trigger the same brain regions as physical pain. The need to belong is not optional. It is hardwired.

Memory, Identity, and the Continuity of Behavior

What would behavior be without memory? Without a sense of past, there can be no consistent sense of self. The hippocampus, located deep within the brain, is responsible for converting short-term experiences into long-term memories. Damage to this area can result in profound amnesia, where a person lives moment-to-moment, unable to recall what just happened.

But memory is not a perfect recording. It is reconstructive, not reproductive. Every time we recall something, we alter it slightly. Memories can be influenced by emotion, suggestion, and context. Yet, despite their flaws, they are central to behavior. Memories guide decisions, shape beliefs, and define relationships.

Identity itself—who we believe we are—is encoded in networks of memory, emotion, and language. Our goals, values, and even personality traits are built atop a lifetime of neural patterns. When someone experiences brain injury or degenerative disease, their behavior can change so drastically that loved ones say, “They’re not the same person.” In some ways, this is literally true. The person we are is a reflection of the brain’s continuity.

Decision Making: The Battle Between Emotion and Logic

Every decision we make, from what to eat for breakfast to whether to quit a job, involves brain activity across multiple regions. The orbitofrontal cortex integrates emotional value with rational analysis. The ventromedial prefrontal cortex weighs risk and reward. The dorsolateral prefrontal cortex handles abstract reasoning and working memory.

But we are not purely rational beings. The emotional brain often acts first. The amygdala can trigger a reaction before the cortex has had time to analyze. This is why we sometimes “snap” or make impulsive choices we later regret.

In many ways, decision making is a dialogue between the emotional and rational brain. Some people are better at balancing the two; others lean heavily toward impulse or overthinking. Neurological disorders, trauma, or even fatigue can shift this balance. Our behavior may feel voluntary, but the machinery driving it is often hidden.

The Brain in Love and Attachment

Perhaps nothing so profoundly illustrates the brain-behavior link as the experience of love. Falling in love floods the brain with dopamine, making us feel euphoric, energetic, and obsessive. The reward centers light up as powerfully as with any drug. At the same time, oxytocin and vasopressin deepen bonds, promoting trust and attachment.

Long-term love activates different systems than infatuation. Over time, novelty gives way to security. The brain’s attachment circuits stabilize, and love becomes less about thrill and more about connection.

Even heartbreak has neurological signatures. Brain scans show that social rejection activates the same pain centers as physical injury. The feeling of a “broken heart” is not poetic—it is physiological. Behavior during love, jealousy, loss, and devotion are all sculpted by the brain.

Mental Illness: When the Brain Behaves Differently

When brain systems malfunction—whether through genetics, trauma, infection, or stress—behavior can change dramatically. Disorders like depression, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and OCD are not failures of character but manifestations of altered brain function.

A person with schizophrenia may hear voices because of overactive dopamine pathways and misfiring auditory regions. Someone with depression may lose interest in life due to underactive reward circuits. These conditions alter perception, motivation, emotion, and behavior.

Understanding that mental illness is brain-based removes stigma and opens the door to empathy and effective treatment. The behaviors associated with mental disorders are not chosen—they are symptoms. Just as a limp reflects an injured leg, unusual behaviors can reflect an injured mind.

Plasticity: The Brain’s Power to Change Behavior

Perhaps the most hopeful discovery in modern neuroscience is neuroplasticity—the brain’s ability to change throughout life. For decades, scientists believed that the brain stopped developing in adulthood. We now know this is false. Learning, therapy, meditation, trauma, and even thought itself can reshape neural pathways.

Behavior is not destiny. With the right interventions—whether through cognitive behavioral therapy, mindfulness, medication, or enriched environments—people can change how they think and act. The brain can heal, grow, and adapt. It is never static.

This plasticity explains how habits are broken, how trauma is overcome, and how personal transformation is possible. The brain does not merely react to experience; it can be shaped by it. We are not prisoners of our biology, but partners in its evolution.

Consciousness: The Mystery That Moves Us

Even with all we’ve learned, one great mystery remains: consciousness itself. How does the firing of neurons produce the subjective experience of being? What does it mean to be aware, to feel, to reflect?

No theory fully explains it. Consciousness may arise from integrated information across brain regions, or from quantum processes within neurons, or from something we’ve yet to imagine. But without it, behavior would be robotic. With it, we become beings capable of joy, suffering, compassion, creativity, and reflection.

The brain influences behavior not only through mechanics, but through meaning. It allows us not just to act, but to understand our actions. In this sense, behavior is more than motion—it is expression. A cry, a laugh, a hesitation, a word—all are echoes of consciousness.

Conclusion: The Brain, the Self, and the Dance of Behavior

The brain is not a machine we operate; it is the operation itself. It is the medium through which we see the world, feel its weight, dream of better days, and act upon its challenges. Behavior is not an accident or a mystery—it is the flowering of neural activity, sculpted by biology and experience.

And yet, within that biological matrix lies astonishing flexibility. We are not fated to repeat our pasts or be bound by our instincts. The same brain that developed fear can learn courage. The same circuits that housed trauma can hold healing. Behavior is the dance of neurons and neurotransmitters, yes—but it is also the dance of hopes, values, stories, and change.

Understanding how the brain influences behavior is not merely a scientific pursuit. It is a journey inward, toward empathy, responsibility, and self-knowledge. In studying the brain, we are not just exploring tissue—we are exploring ourselves.

And the more we learn, the more wondrous it becomes. That such a fragile, fatty organ could generate art, morality, memory, and love is a miracle not yet fully understood. But it is a miracle we live every day, with every breath, every thought, and every action.