Recent advancements in the field of archaeogenetics have unearthed groundbreaking revelations about the genetic makeup of early medieval European populations. Researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, collaborating with an international team, conducted a comprehensive genetic study of human remains from two significant burial sites—Mödling and Leobersdorf, both located south of Vienna. The study, which analyzed remains from over 700 individuals, sheds new light on the social and genetic complexities of a period characterized by migration and cultural assimilation. Published in the journal Nature, the study explores the intricate relationship between genetics, culture, and social identity during the Avar period of the 8th century CE.

A Surprising Discovery: East Asian and European Ancestry in Neighboring Sites

The Avars, a nomadic people who arrived in Central Europe from the East Asian Steppes in the 6th century, brought with them a mix of cultures and traditions that would shape the region’s social dynamics. As the Avars settled in what is today Hungary, Austria, and parts of Romania, they encountered indigenous populations who had long been established in the area. This historical backdrop raised significant questions regarding the genetic and cultural assimilation of these diverse groups.

Until now, much of the archaeological and historical literature suggested that, over time, these populations gradually mixed, forming a homogenized Avar society. However, the findings from this latest archaeogenetic study challenge this assumption, offering surprising results that suggest a far more complex narrative.

The two burial sites—Mödling, which had over 500 graves, and Leobersdorf, with nearly 150—were located just a few kilometers apart but exhibited stark genetic differences. The inhabitants of Leobersdorf were primarily of East Asian genetic origin, closely related to the Avar invaders from the Steppe. In contrast, the individuals buried in Mödling exhibited genetic ancestry typically associated with European populations, suggesting that they were likely part of the indigenous population of the region.

“The genetic difference between these groups was very clear and consistent for most individuals at the sites,” says Ke Wang, one of the lead authors of the study and a geneticist at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. This stark contrast was unexpected, especially considering the fact that both burial grounds and their associated archaeological cultures were highly similar.

Cultural Integration Despite Genetic Differences

The genetic dissimilarities between the populations of Mödling and Leobersdorf raise intriguing questions about the relationship between cultural identity and genetic heritage. According to Walter Pohl, a historian and senior author of the study, “The cultural integration apparently worked despite major genetic differences, and these people were obviously regarded as Avars.” The archaeological evidence supports this assertion, as both groups shared similar customs, including similar burial practices, grave goods, and social symbols, despite the distinct genetic backgrounds.

Interestingly, the period during which these communities coexisted, spanning at least six generations, was one of relative peace in the Vienna Basin, contradicting the traditional portrayal of the Avars as fierce warriors. “We find no battle injuries on the skeletons, and there are hardly any signs of deficiencies,” explains Doris Pany-Kucera, an anthropologist at the Natural History Museum in Vienna. Weapons were rarely placed in graves, suggesting a non-combative way of life during this time, further underscoring the contrast with the violent image that is often associated with Avar history.

Genetic Structure and Social Dynamics

The researchers employed a combination of rigorous archaeological methodologies and cutting-edge genetic analysis to understand the social dynamics of these communities. Their study provides valuable insights into family structures and mating patterns within these groups. By mapping contemporary pedigrees over six generations, the researchers were able to uncover familial connections among individuals at each site. According to Zuzana Hofmanová, another lead author and geneticist, “The large number of genetic relationships between the individuals allowed us to reconstruct contemporary six-generation-long pedigrees at each site.”

One of the most intriguing findings of the study was the absence of local ancestors among most of the mothers in both burial sites. This suggests that women were marrying into these communities from external populations, potentially contributing to the genetic divergence between Mödling and Leobersdorf. Interestingly, while the women of Leobersdorf were likely from communities of East Asian descent (possibly from the heart of the Avar realm), the women of Mödling were of European origin. Despite these divergent genealogies, there were no significant differences in status or wealth between the individuals at Mödling and Leobersdorf, further challenging the notion that cultural differences necessarily align with genetic background.

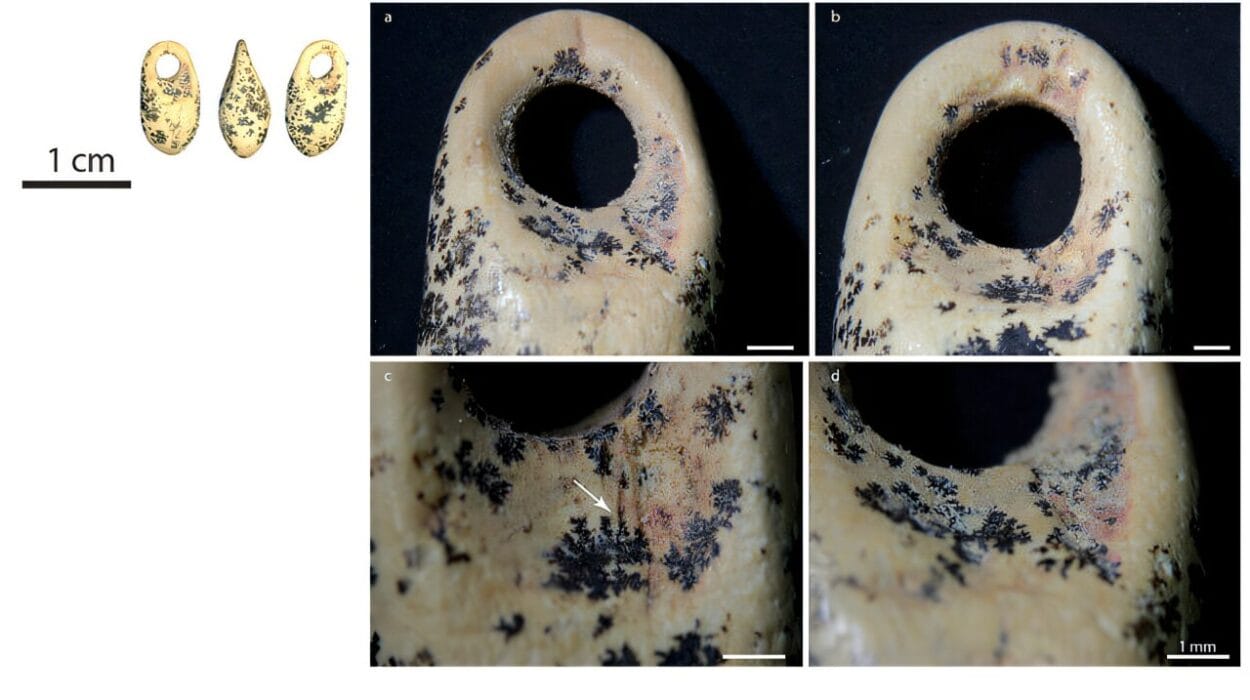

Bendeguz Tobias, an archaeologist and co-author of the study, adds, “Status symbols such as belt fittings depicting griffins, and their culture and customs were the same. Most likely both considered themselves Avars.” This reinforces the idea that identity and cultural affiliation were not strictly tied to genetic heritage but rather to shared practices and beliefs, which provided a sense of belonging for both groups.

The Legacy of the Avar Period: Insights into Migration and Social Integration

The findings from Mödling and Leobersdorf not only illuminate the genetic history of the Avar period but also have far-reaching implications for the broader study of migration and social integration in early medieval Europe. The fact that these two populations coexisted peacefully for several generations—despite their stark genetic differences—raises important questions about how ancient societies viewed identity and community.

In the case of the Avars, their integration into the local societies was not a simple process of genetic assimilation but rather one of cultural syncretism, wherein people of different genetic backgrounds adopted similar customs, shared social symbols, and identified with a common cultural group. The idea of social integration across genetic boundaries challenges more traditional understandings of how cultures evolve during periods of migration, offering valuable lessons for modern discourses on multiculturalism and integration.

Moreover, the success of genetic sampling and analysis in this study paves the way for future archaeogenetic research. As Johannes Krause, director of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology and one of the senior authors of the study, notes, “Mödling burial ground is one of the largest ever analyzed genetically, and such results hold a lot of potential for future research in various disciplines.” This study is just one example of how advances in genetic technology can unravel complex aspects of our history, providing new insights into ancient societies and challenging long-held assumptions about the past.

Conclusion

The archaeogenetic study of the burial sites at Mödling and Leobersdorf has provided a fresh perspective on the genetic and cultural landscape of Early Medieval Europe. Far from being a straightforward case of Avar conquest and assimilation, these findings suggest a more nuanced relationship between genetic heritage, social structure, and cultural identity. The coexistence of two genetically distinct groups, both adopting similar cultural practices and identifying as Avars, highlights the complex ways in which humans form societies and construct their identities across generations. As this research continues to unfold, it offers exciting possibilities for a deeper understanding of the multifaceted history of migration, integration, and cultural exchange in the medieval world.

Reference: Ke Wang et al, Ancient DNA reveals reproductive barrier despite shared Avar-period culture, Nature (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-024-08418-5