For as long as humans have gazed upward, we’ve asked a question that cuts deeper than science—it strikes at the very core of our identity: Are we alone?

It’s a question that has haunted myth, inspired philosophy, and driven some of the most sophisticated space exploration of our time. But as telescopes probe deeper into the universe, and scientists catalogue more Earth-like planets circling alien suns, another question emerges—one even more tantalizing:

Could life, as we know it, survive out there?

Now, a curious, sunburnt lichen from the Mojave Desert might just hold the key to that answer.

Born in the Desert, Tested by the Stars

Beneath the scorching sun of southern Nevada, in the arid Mojave Desert, a fragile-looking lifeform clings to rocky outcrops. It looks unassuming, even brittle. But Clavascidium lacinulatum—more commonly just called a desert lichen—possesses a secret.

This lichen doesn’t just survive extreme heat and dryness. It wears what may be the most powerful natural sunscreen known to science—one that can fend off the deadliest solar radiation in the universe.

In a new study published in the journal Astrobiology, researchers exposed this unremarkable yet extraordinary lifeform to intense ultraviolet radiation that would instantly sterilize most organisms. The kind of UVC radiation that other planets—particularly those orbiting flaring stars—receive in abundance. And the results were shocking.

After three relentless months under UVC radiation in a controlled lab experiment, the lichen wasn’t just alive. It was replicating.

A Walk That Sparked a Scientific Breakthrough

The inspiration for the study wasn’t born in a laboratory—it began with a walk in the desert.

Dr. Henry Sun, a microbiologist and associate research professor at the Desert Research Institute (DRI), wasn’t hunting for alien analogues when he noticed something odd. The lichens growing on desert rocks weren’t green, as one might expect from photosynthetic organisms. They were black.

“I was just walking in the desert and I noticed that the lichens growing there aren’t green, they’re black,” Sun recalled. “They are photosynthetic and contain chlorophyll, so you would think they’d be green. So I wondered, ‘What is the pigment they’re wearing?’ And that pigment turned out to be the world’s best sunscreen.”

What began as a moment of curiosity soon transformed into a rigorous scientific investigation—one that could change how we search for life in the cosmos.

The Radiation Nobody Survives

To appreciate the magnitude of the lichen’s endurance, it helps to understand the threat they were up against.

Ultraviolet light, the type that gives us sunburns, comes in three forms: UVA, UVB, and UVC. Earth’s atmosphere filters out nearly all of the deadly UVC rays before they reach the surface, leaving life to evolve in relative safety. But UVC radiation is so harmful that it’s used to sterilize hospital rooms, purify drinking water, and even clean spacecraft.

It shreds DNA. It breaks chemical bonds. Even a short exposure can render most living organisms lifeless.

And yet, many of the Earth-like exoplanets astronomers are discovering orbit stars known as M-dwarfs or F-type stars. These suns flare frequently, bathing nearby planets in massive doses of UVC radiation—enough to make the idea of life seem improbable, if not impossible.

Until now.

The Experiment That Defied Expectations

Together with then-graduate student Tejinder Singh—now a researcher at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center—Sun collected samples of Clavascidium lacinulatum from the desert near Las Vegas. The lichens were placed in a specially designed laboratory environment and subjected to UVC radiation continuously for three months. This wasn’t a brief shock of light. It was a trial of endurance.

Half of the algal cells in the lichen survived. And when rehydrated, they began to replicate.

But how?

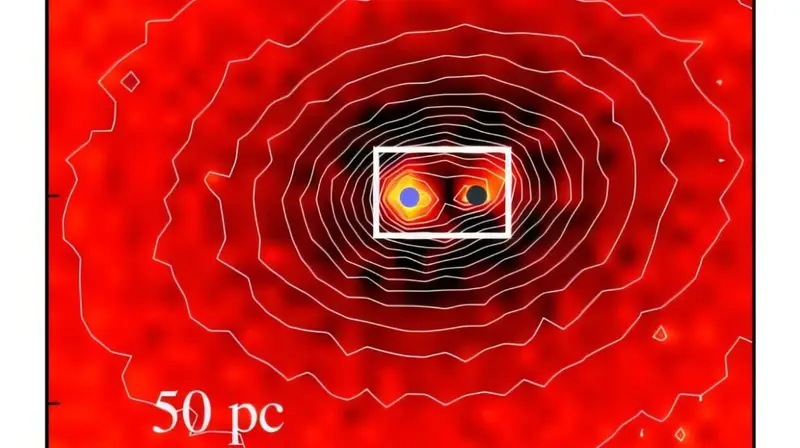

To understand the biological sorcery that allowed this resilience, Sun teamed up with chemists from the University of Nevada, Reno. They discovered that the lichens were coated in powerful lichen acids—compounds that function almost exactly like industrial photostabilizers used to protect plastics from sunlight.

And just like a tan forms on human skin as a response to sunlight, the lichens had evolved a natural armor. When the scientists cut open the lichen and analyzed its structure, they found that the outermost layer—the “skin”—was the darkest. A literal shield.

Strip away that protective coat, and the algae underneath were instantly killed by UVC in under 60 seconds.

Evolution’s Bonus Gift

What makes the discovery even more fascinating is that lichen didn’t need this UVC protection to survive on Earth. By the time they evolved, Earth’s thick atmosphere had long since filtered out UVC radiation.

This means the trait may be evolutionary overkill—a natural bonus. Or, perhaps, it’s a deep-time echo from a more dangerous era, a molecular relic of life adapting to hostile skies in Earth’s ancient past.

It’s a feature that makes lichen uniquely suited to imagining life on other planets. Unlike humans, who must build spacecraft to explore alien worlds, the lichen doesn’t need a helmet.

It brings its own.

Alien Atmospheres, Terrestrial Survivors

To simulate extraterrestrial conditions even more accurately, the researchers ran a second set of tests—this time, placing the lichen in an oxygen-free environment with UVC exposure. Oxygen is known to interact with UV radiation and generate damaging compounds like reactive oxygen species and ozone, both of which can harm cells.

Stripped of this added chemical stress, the lichen fared even better. Its top layer—a mere millimeter thick—acted not just as a UV shield but also as a barrier to harmful atmospheric reactions.

“The lichen’s skin acts as a photostabilizer,” Sun explained. “It protects the living cells underneath not just from direct radiation, but also from chemical byproducts like ozone.”

This adaptation could make all the difference on a planet orbiting a flaring star, where chemical interactions might otherwise devastate fragile life.

The Implications: Life Is More Tenacious Than We Imagined

The broader implications of this discovery stretch across galaxies. If a simple Earth organism like lichen can survive—and even thrive—under extreme UVC radiation, then our current assumptions about habitability may be far too narrow.

For decades, the search for life beyond Earth has been constrained by what we know: life needs water, an atmosphere, and a relatively calm star. But perhaps, life doesn’t need a perfect planet. Perhaps, it just needs time. And shade. And the evolutionary ingenuity to develop a good sunscreen.

“This work reveals the extraordinary tenacity of life even under the harshest conditions,” said Singh. “It’s a reminder that life, once sparked, strives to endure.”

A New Lens for Exoplanet Exploration

The study arrives at a critical moment in the search for life. Since the launch of the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), astronomers have peered deeper into the cosmos than ever before, identifying planets with atmospheres, oceans, and even potential biosignatures.

But many of those planets orbit stars previously thought to be too hostile. The lichen’s resilience rewrites that assumption.

“Now we know that photosynthetic life isn’t necessarily ruled out just because a planet receives high levels of UVC,” Sun said. “We need to rethink what kinds of life are possible—and where we might find it.”

If life can survive deadly radiation wrapped in fungal armor, then microbial colonies may already be thriving in alien deserts, clinging to the dark rocks of a distant world, silently photosynthesizing under a sun more violent than our own.

A Humble Organism, A Cosmic Revelation

The discovery doesn’t just expand our scientific models. It stirs something deeper—a sense of wonder that the answers to cosmic questions may not come from distant galaxies, but from the cracks in a Nevada rock.

There, a quiet symbiosis between fungus and algae is showing us what life is capable of. That survival isn’t always about strength. Sometimes, it’s about adaptation. About patience. About outsmarting the universe’s harshest elements with elegant simplicity.

The story of Clavascidium lacinulatum is more than a tale of scientific resilience. It’s a parable about life’s ingenuity. A testament that even in a universe filled with radiation, chaos, and violence, nature finds a way to persist.

And if it can do so here, it just might be doing so out there.

Reference: Tejinder Singh et al, UVC-Intense Exoplanets May Not Be Uninhabitable: Evidence from a Desert Lichen, Astrobiology (2025). DOI: 10.1089/ast.2024.0137