Evolution is one of the most transformative and unifying theories in all of science. It explains not only the diversity of life we see today but also our own origins. Yet, despite the overwhelming scientific evidence and more than 160 years since Darwin’s On the Origin of Species was published, evolution remains one of the most misunderstood concepts in public discourse. Its very name often sparks confusion, suspicion, or outright denial. Why?

The problem lies not with the theory itself, which has stood the test of time, experimentation, fossil records, and molecular biology. The problem is with the myths—those persistent, often emotionally charged misunderstandings that cloud the clarity of what evolution really means.

These myths endure not because they hold merit, but because they offer simplicity. Evolution, by contrast, demands a willingness to embrace complexity, nuance, and deep time—concepts that don’t always fit neatly into our everyday experiences. But for those willing to look closer, the truth is far more compelling than the myths ever were.

Evolution Is “Just a Theory”

One of the most enduring misconceptions is rooted in language itself. When people hear the word “theory,” they often equate it with a guess or a hunch—something unproven or speculative. This is not how scientists use the term.

In science, a theory is a well-substantiated explanation of some aspect of the natural world that incorporates facts, laws, inferences, and tested hypotheses. Evolution, in this context, is as solid a theory as gravity, germ theory, or the theory of plate tectonics. It is not “just” a theory. It is a theory in the highest scientific sense, built on mountains of evidence gathered from fossil records, comparative anatomy, embryology, molecular biology, and genetics.

Confusion arises because theories can evolve themselves—refined over time as new data come in. But refinement is not weakness. It’s the hallmark of good science. The robustness of evolution lies in its ability to accommodate new discoveries without collapsing.

Humans Did Not Evolve From Monkeys

This myth stems from a misunderstanding of both the fossil record and the tree-like structure of evolutionary relationships. No reputable biologist claims that humans evolved from modern monkeys or apes. Rather, humans and modern primates share a common ancestor that lived millions of years ago.

Think of evolution not as a ladder but as a branching tree. At some point in the past, one branch led to what we now recognize as the great apes—chimpanzees, gorillas, orangutans—while another led to the hominin line, ultimately giving rise to Homo sapiens. Monkeys and humans are evolutionary cousins, not ancestors and descendants.

This is further supported by genetic evidence. Humans share about 98–99% of our DNA with chimpanzees. The similarities aren’t accidental—they’re inherited from a shared lineage. But the divergence happened long ago, and both lineages continued evolving separately ever since. We did not descend from the monkeys we see in zoos; we and they are both survivors of ancient populations that lived in environments long vanished.

Evolution Has a Direction or Purpose

Another widespread myth is the idea that evolution is marching toward some predetermined goal—often imagined as increasing complexity, intelligence, or perfection. This is a comforting notion, but it’s not how evolution works.

Natural selection does not have foresight. It does not “want” to create better organisms. It simply favors traits that enhance survival and reproduction in a given environment. What counts as “better” can change over time as the environment changes.

Evolution is not a straight line leading from bacteria to humans. It is a branching, bushy process with countless dead ends and side paths. Bacteria, by the way, are still here, still thriving, and still evolving. In many ways, they are more successful than humans. They have survived for billions of years and exist in environments we can’t tolerate—from boiling hot springs to the depths of the ocean.

Humans are not the pinnacle of evolution. We are one twig on a vast, sprawling tree of life. Intelligence, while useful to us, is not necessarily the ultimate trait. In evolutionary terms, the “fittest” is not the strongest, smartest, or most beautiful—it is whatever works best to leave behind offspring in a specific context.

There Are No “Missing Links”

Critics of evolution often ask: where are the missing links? They imply that without a perfect chain of fossils showing each incremental step from one species to another, evolution is baseless. But this is a misunderstanding of how both fossilization and evolution work.

First, fossilization is rare. Most organisms that die decay completely, leaving no trace. Fossils are usually formed only under specific conditions—rapid burial, mineral-rich environments, and low oxygen. Given that, it’s remarkable how many transitional fossils we have found.

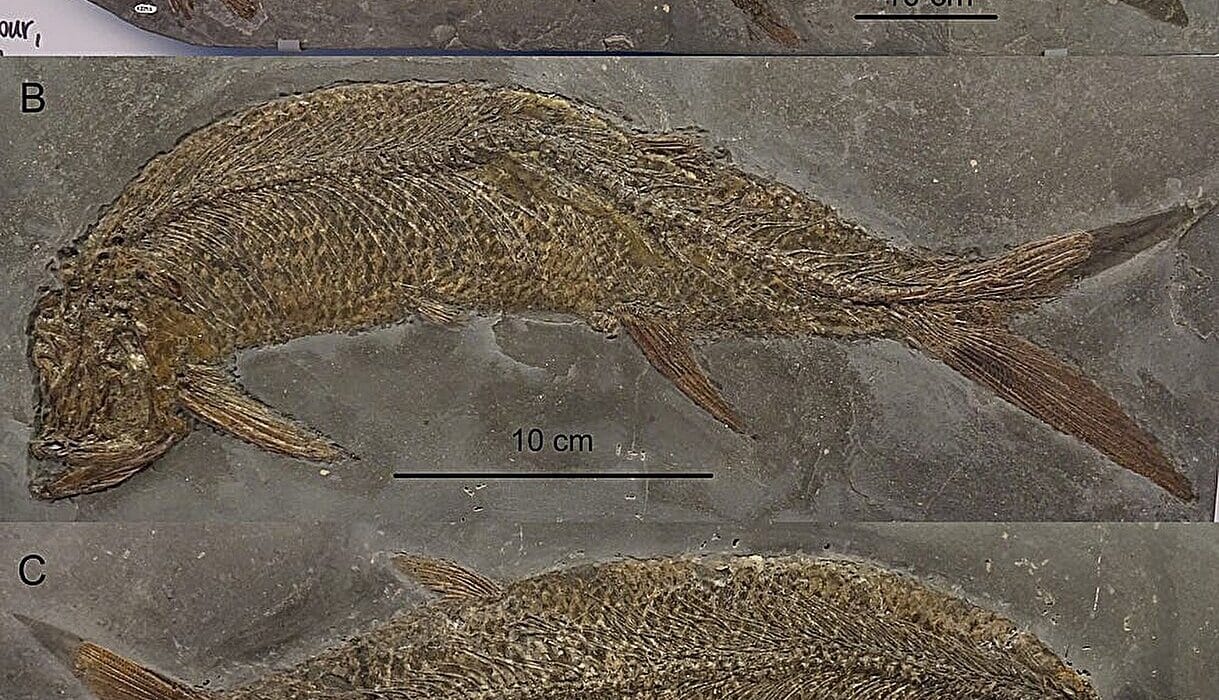

Second, evolution doesn’t work in straight lines. It’s more like a web with many interwoven strands. Transitional forms do exist, but they don’t always look like half-and-half mixtures. For example, Archaeopteryx shows both bird and reptile traits, and numerous hominin fossils—Australopithecus, Homo habilis, Homo erectus—show clear gradations in skull size, tool use, and bipedalism.

The term “missing link” itself is misleading because it implies that evolution should produce a neat sequence, like beads on a string. But species don’t evolve in clean, sequential lines. They branch, diverge, and often go extinct. The fossil record is not a ladder; it’s a messy archive of survival, extinction, and adaptation.

Evolution and Religion Are Incompatible

This myth pits science against spirituality in a way that’s unnecessary and often divisive. While it’s true that some religious groups reject evolution, many others embrace it. The Catholic Church, for instance, officially accepts evolutionary theory, as do many Protestant, Jewish, Hindu, and Buddhist traditions.

Evolution deals with the how of life’s diversity, not the why of existence. It is a scientific explanation for natural phenomena, not a philosophical or theological statement. Belief in evolution does not require atheism. Many scientists are religious, and many believers accept the evidence for evolution without feeling that it threatens their faith.

The conflict arises mostly when people take sacred texts as literal, scientific documents rather than spiritual or metaphorical narratives. The Bible, Quran, or other holy books were not written to describe genetic drift, speciation, or allele frequencies. They serve different purposes, and recognizing this can ease the tension between faith and science.

Evolution Can’t Explain Complex Organs Like the Eye

One of the most emotionally compelling arguments against evolution is the claim that some organs are “irreducibly complex”—that they could not function if even one part were missing. The human eye is often used as an example.

But this argument misunderstands how complexity can evolve. The eye did not appear all at once. It evolved in stages, each providing a survival advantage. Even a simple light-sensitive patch can help an organism detect day from night. A curved patch can give directional information. A cup-shaped structure provides crude image-forming ability. Adding a lens sharpens the image further.

We see all these forms in nature today, in creatures ranging from flatworms to octopuses. The eye did not emerge from nowhere. It was shaped gradually, over millions of years, with each improvement offering an advantage in detecting predators, prey, or mates.

Complexity can emerge from simplicity, given enough time and natural selection. The human eye is not flawless—far from it. It has blind spots, is wired backward, and is prone to degeneration. That’s not evidence of design perfection—it’s evidence of tinkering through evolutionary trial and error.

Microevolution Is Real, but Macroevolution Is Not

Some argue that evolution can produce small changes—like different beak shapes in finches—but not big ones, like turning a fish into an amphibian. This supposed distinction between “microevolution” and “macroevolution” is more semantic than scientific.

Microevolution refers to small-scale changes within a species—often driven by shifts in gene frequency. Macroevolution describes broader patterns that result in the emergence of new species, genera, or even higher taxonomic groups. But these are not fundamentally different processes. Macroevolution is microevolution extended over longer timescales.

Speciation—the formation of new species—has been observed both in nature and in the lab. Fruit flies, plants, and bacteria have all shown this capacity. Given time, reproductive isolation, and selection pressures, small changes accumulate and eventually lead to major differences.

The line between micro and macro is blurry, not a scientific wall. The accumulation of small changes is how large changes arise.

Evolution Means Life Is Random and Meaningless

Perhaps the most emotionally distressing myth is the belief that evolution implies life has no meaning. This view often stems from a misunderstanding of natural selection as purely random.

While mutations—the raw material of evolution—do arise randomly, natural selection is not random. It is a consistent, directional process that favors traits increasing survival and reproduction. Evolution is not chaos. It is a dance between chance and necessity.

Moreover, scientific explanations do not negate human meaning. Saying that stars are giant nuclear furnaces doesn’t make sunsets less beautiful. Likewise, saying that humans arose through natural selection does not strip life of value. If anything, it makes our existence even more wondrous. We are the product of 4 billion years of survival, adaptation, and resilience. That story is no less poetic than any creation myth.

Meaning is something humans create—through relationships, creativity, love, knowledge, and self-awareness. Evolution doesn’t deny that. It helps us understand where we came from. The rest is up to us.

Evolution Is Too Slow to Observe

There’s a popular belief that evolution takes millions of years and can’t be observed in real-time. But this is untrue. Evolution has been documented within human lifespans.

Antibiotic resistance in bacteria is one of the most dramatic examples. Bacteria evolve quickly because they reproduce rapidly. When exposed to antibiotics, the few with resistance genes survive and multiply. Over time, an entire population can become resistant—a clear example of evolution in action.

Similar processes occur in viruses, pests, and invasive species. HIV evolves resistance to antiviral drugs. Mosquitoes evolve resistance to pesticides. Even urban animals are evolving traits to survive in cities.

We’ve also seen evolution in the lab. Researchers have tracked generations of fruit flies and bacteria, observing changes in behavior, metabolism, and even the development of new functions. Evolution is not only real—it’s happening around us all the time.

A Theory That Illuminates Everything

The myths about evolution endure not because they are strong but because they are familiar. They offer comfort, simplicity, or a way to avoid the discomfort of changing one’s worldview. But truth doesn’t require comfort to be beautiful.

Evolution is not a threat to wonder—it is its companion. It reveals how every living thing is connected, how life adapts and survives, and how the human mind is a continuation of processes that began in ancient oceans billions of years ago.

Darwin himself once wrote: “There is grandeur in this view of life.” And he was right. There is grandeur in knowing that we are part of an unbroken chain stretching back to the earliest cells. There is wonder in understanding that every cell in our body carries the echoes of deep time. And there is humility in realizing that we are still evolving, still changing, still discovering.

Evolution does not diminish us. It makes us part of a larger story—one still unfolding, one still worth telling, and one still bursting with questions we have yet to answer.