Some questions rattle the soul of science. They crawl into the deepest chambers of our understanding and whisper provocatively: What if you are no longer merely the outcome of evolution? What if, instead, you are its author?

For centuries, evolution was something that happened to us. It was something that carved us from the clay of randomness, shaping us over eons through hunger, fear, mutation, and chance. We were its product, never its master. But today, that long-standing relationship is shifting. Slowly, quietly, and with consequences we are only beginning to fathom, humans have begun to steer the course of their own biological future.

So the question, “Can we direct our own evolution?” isn’t merely scientific—it is existential. It forces us to examine not just what we are becoming, but whether we are ready to become it.

From Passive Participants to Curious Architects

To understand how we reached this pivotal moment, we must first acknowledge where we came from. For over 3.5 billion years, life on Earth evolved through natural selection, genetic drift, mutation, and other blind forces. Species lived or died depending on their ability to adapt, survive, and reproduce. Evolution was not guided by intent. It had no foresight, no goal. It just happened.

Humans were no different. Our brains, bipedal gait, and opposable thumbs were not the result of deliberate planning. They emerged through a cascade of tiny genetic changes, shaped by environmental pressures and sheer luck. And while we eventually learned to tame fire, build tools, and write symphonies, the DNA blueprint that made it all possible was beyond our control.

But something changed in the last century—a revolution so profound that it altered our evolutionary role. For the first time in the history of life, a species became capable of understanding the code that made it. Not only understanding it but rewriting it.

The Dawn of Genetic Mastery

It began with the discovery of DNA in the mid-20th century. The double helix wasn’t just a chemical curiosity—it was the instruction manual of life, written in four simple letters: A, T, C, and G. Suddenly, the seemingly mystical processes of inheritance and variation had a physical form. Scientists could now peer into the very language of evolution.

From there, the pace quickened. The Human Genome Project, completed in 2003, decoded the 3 billion letters of our DNA. This colossal achievement gave us the first map of the human blueprint. We saw, in stunning detail, the genes responsible for eye color, disease susceptibility, and even behavioral traits. We began to see how small variations could ripple across generations and societies.

But the ability to read DNA was just the beginning. The more tantalizing power came later: the ability to edit it.

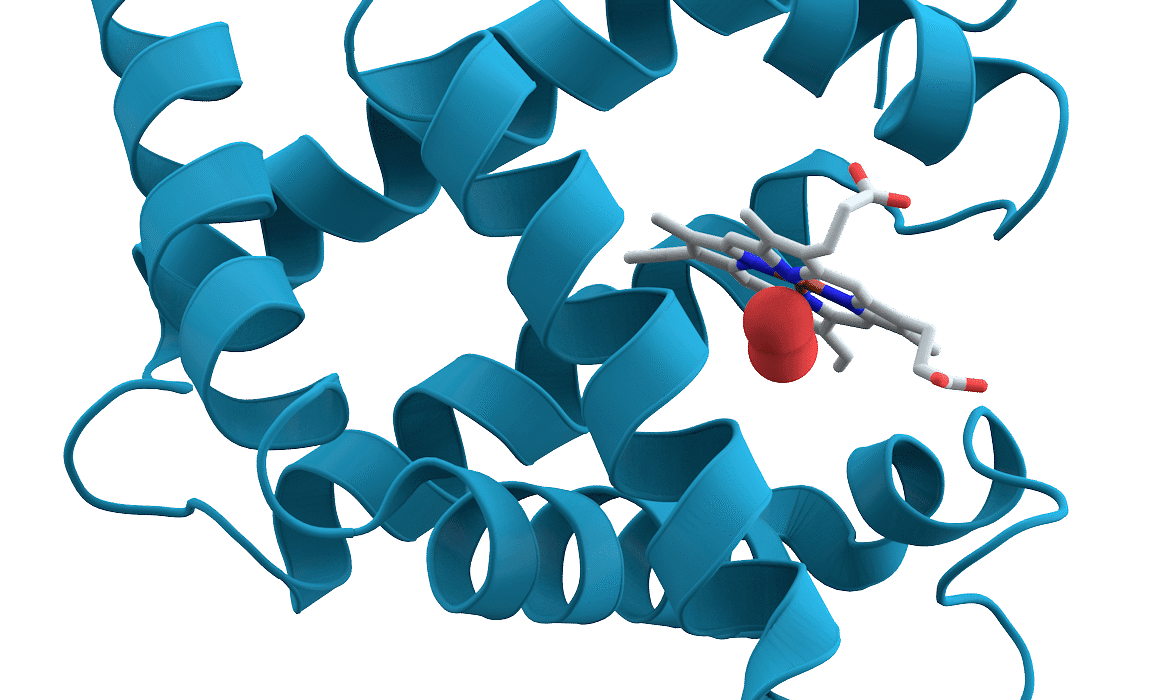

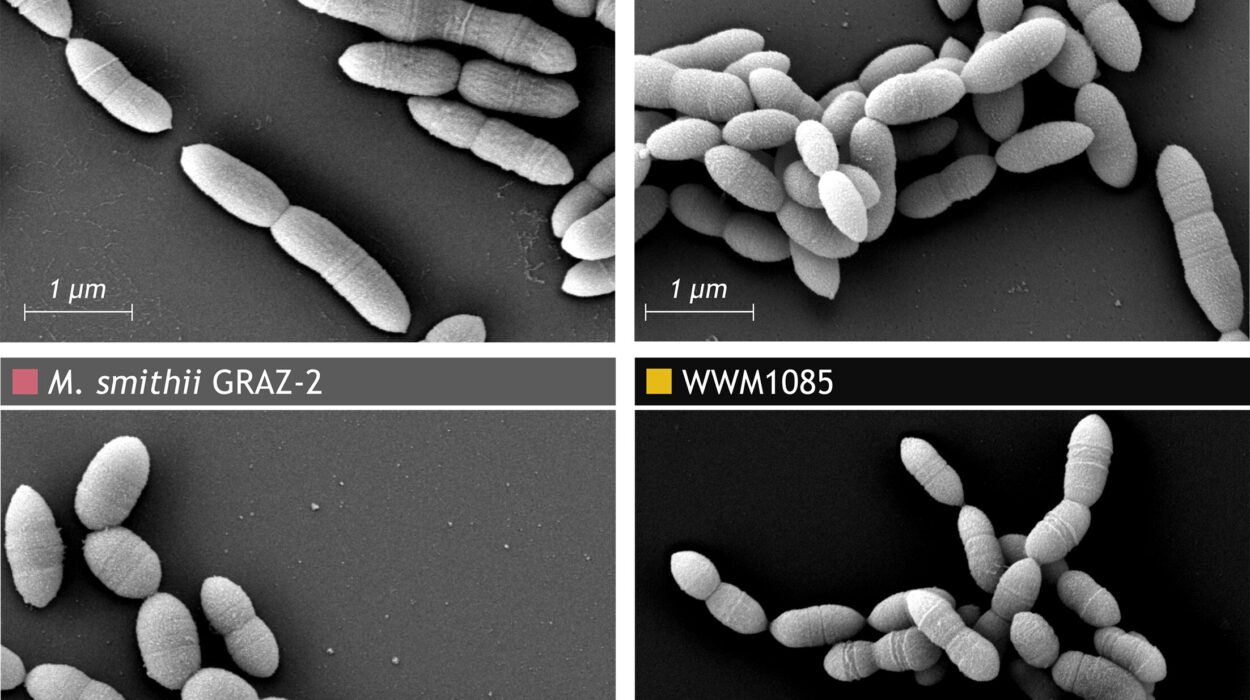

Enter CRISPR-Cas9, a gene-editing tool so precise, so revolutionary, that it was likened to a molecular scalpel. With CRISPR, scientists could cut and paste genes with remarkable accuracy. Suddenly, it was possible to delete genes that cause genetic disorders—or insert new ones. The doors to genetic enhancement, disease eradication, and even human redesign had swung wide open.

Evolution By Choice, Not Chance?

Directing our own evolution means that change is no longer random. It implies that human beings can now alter the inherited traits of themselves or their offspring—not over millennia, but within a generation.

This raises thrilling possibilities. Could we eliminate hereditary diseases like Huntington’s or cystic fibrosis? Could we boost resistance to viruses or slow the aging process? Could we enhance memory, intelligence, or strength?

Theoretically, yes. But theory and practice are not the same. To direct evolution, we must first confront a maze of biological complexity, ethical dilemmas, and social consequences. Because evolution is not just about genes. It’s about interactions—between genes, environments, cultures, and technologies.

For example, a gene associated with high intelligence might also increase the risk of certain mental illnesses. Boosting muscle growth could affect metabolism or lifespan. Nature has never offered free lunches, and biology often works through trade-offs.

Moreover, traits like intelligence, empathy, or creativity are polygenic, meaning they involve the interaction of hundreds or even thousands of genes, influenced by environment, education, and culture. Editing one gene might barely move the needle—or produce unintended consequences.

Still, the seeds have been planted. Already, CRISPR has been used to modify human embryos in laboratory settings. In 2018, the world was stunned when a Chinese scientist announced the birth of twin girls whose genomes had been altered to resist HIV. The act was widely condemned, not because it was scientifically impossible, but because it was ethically premature.

Yet the genie is out of the bottle. The question is no longer “can we?” but “should we?” and “how far?”

From Healing to Enhancing

Human intervention in evolution isn’t new. For thousands of years, we’ve used selective breeding to guide the development of crops, livestock, and pets. We domesticated wolves into dogs, turned wild grasses into corn, and bred horses for speed or strength. This, too, was a kind of evolutionary steering—though slow and imprecise.

Modern medicine also plays a role. Vaccines, antibiotics, and surgical procedures have changed the selective pressures on human populations. Traits that might have once led to early death—like nearsightedness or genetic disorders—no longer remove individuals from the gene pool. In a sense, we’ve already softened natural selection.

But what we’re contemplating now goes beyond this. It moves from therapy to enhancement, from survival to transcendence.

Enhancement means giving future generations traits that are not strictly necessary for survival but are desirable. Faster reflexes, greater height, longer life, resistance to mental decline, perhaps even altered emotional ranges or sensory perception.

Some argue this is the next step in human evolution—a natural progression in a species that has always sought to overcome its limitations. Others see it as a dangerous flirtation with eugenics, inequality, and the unknown.

What happens if only the wealthy can afford genetic upgrades? Do we risk creating a genetic underclass? Will society split into the modified and the natural, the enhanced and the obsolete?

These aren’t hypothetical concerns. The technologies are real. The market incentives are strong. The path forward will require not just science, but wisdom.

The Role of Culture and Environment in Evolution

While gene editing captures our imagination, it’s not the only way humans direct their evolution. Culture—arguably our greatest evolutionary tool—plays a massive role in shaping how our genes express themselves and which ones are passed on.

Language, education, diet, and technology all create environments that influence survival and reproduction. For instance, literacy and numeracy are not determined by genes alone but are shaped by cultural exposure. Yet these skills affect who succeeds, who reproduces, and who influences the future.

The digital age has created a new kind of evolutionary environment. Algorithms, screens, and artificial intelligence affect how we learn, socialize, and even mate. Online dating apps, for example, subtly shape partner selection and thereby the next generation’s gene pool.

Climate change, urbanization, and globalization are also shifting the pressures on human adaptation. In some ways, evolution is accelerating—not because of mutations, but because environments are changing faster than ever before.

Some scientists propose that humanity has entered a new phase called “self-directed evolution,” where genetic and cultural changes are no longer passive responses to nature but the result of conscious choice. Whether this phase leads to liberation or catastrophe depends on how wisely we navigate it.

Artificial Intelligence and the Evolutionary Interface

There is another layer to this conversation—one that blurs the line between biology and technology. As artificial intelligence grows in capability, we are developing systems that not only augment our thinking but could eventually merge with it.

Some transhumanists envision a future in which humans evolve beyond biology altogether, uploading minds into machines, designing synthetic bodies, or fusing with AI to create a hybrid species. To them, evolution is not a fixed track but an open road.

This vision is controversial and speculative. It raises profound philosophical questions about identity, consciousness, and mortality. Are we still human if our memories reside in silicon? Can evolution continue without DNA?

Whether or not these scenarios materialize, the trend is clear: we are building tools that fundamentally reshape the human experience. If evolution is about adaptation, then the integration of AI into our cognitive and social systems may be one of the most significant evolutionary events in history—not through genes, but through interfaces.

Ethical Evolution: The Need for a Moral Compass

With great power comes the need for great reflection. The ability to direct evolution demands not just technical skill but moral vision. Science can tell us how to change ourselves. It cannot tell us why we should—or when to stop.

One of the core ethical dilemmas is consent. A genetically edited embryo cannot agree to the changes being made. Decisions are made by parents, scientists, or governments. Who gets to decide what traits are desirable or acceptable? What values guide these choices?

History is filled with examples of pseudoscience and prejudice masquerading as progress. The eugenics movement of the early 20th century, which sought to “improve” the human race through forced sterilization and discriminatory policies, is a chilling reminder of what happens when evolutionary control falls into the wrong hands.

To prevent future abuse, transparent governance, public dialogue, and global cooperation are essential. Evolution is not just a scientific process—it’s a human one. If we’re going to guide it, we must do so with humility, diversity, and justice in mind.

Could We De-Evolve or Go Back?

In thinking about future evolution, it’s worth asking: can evolution go in reverse? Could we “de-evolve” by undoing certain adaptations or reverting to older forms?

In one sense, the answer is yes. If a trait becomes disadvantageous in a new environment, it may disappear over generations. Whales, for example, evolved from land-dwelling mammals and lost their hind limbs. Cave-dwelling animals have lost their eyes due to disuse. Evolution doesn’t have a preferred direction—it only cares about fitness.

For humans, this means that if technologies like CRISPR or AI reduce the need for certain traits—like strong memory, spatial reasoning, or physical endurance—those traits may decline over time. But in the era of self-directed evolution, we could also choose to reintroduce or preserve them artificially.

So while evolution never truly goes backward, it can take unexpected detours. And now, we have a hand on the steering wheel.

The Future: Mastery or Myth?

Can we direct our own evolution?

Yes—at least partially, and increasingly so. We already do it through medicine, technology, culture, and now genetic science. The tools exist. The decisions are ours.

But the deeper question is: what kind of species do we want to become? Do we aim for perfection, resilience, empathy, intelligence? Do we eliminate suffering—or risk losing some essential part of our humanity in the process?

There is no simple answer. Evolution has always been a dance between chance and necessity. Now, human choice enters the choreography. We are no longer just products of biology—we are participants in its future.

And that future will not be shaped in labs alone. It will be shaped in conversations, classrooms, homes, and communities. It will be shaped by values, fears, dreams, and stories. Evolution may still be a biological process, but its direction—more than ever before—depends on us.

So perhaps the most revolutionary idea of all is not that we can direct our evolution, but that we must. With eyes open, hearts wise, and minds humble, we now step into a new epoch—one in which we are both the sculptors and the stone.