Artificial intelligence has become one of the defining technologies of the twenty-first century, transforming how humans analyze data, design materials, discover medicines, and understand complex systems. Alongside this promise, however, has emerged a deep and persistent fear: the idea that AI could be used to create biological weapons. This concern often appears in stark headlines and speculative narratives, where algorithms become architects of catastrophe and machines cross a threshold into deliberate mass harm. To ask whether AI can create a biological weapon is therefore not merely a technical question. It is a question that touches science, ethics, security, and the fragile relationship between human ingenuity and responsibility.

To approach this issue responsibly, it is essential to separate what is scientifically plausible from what is sensational, and what is theoretically possible from what is practically achievable. Biological weapons are among the most tightly controlled and morally condemned tools ever devised by humanity. Their development requires deep biological knowledge, specialized infrastructure, and a willingness to violate international law and ethical norms. AI, by contrast, is a tool for pattern recognition, prediction, and optimization. Understanding how these two domains intersect requires careful analysis rather than alarmism.

This article explores the dark potential often attributed to AI in the biological realm, while grounding the discussion in scientific accuracy. It examines what biological weapons actually are, what AI can and cannot do, where legitimate risks exist, and why human oversight, governance, and scientific culture remain decisive factors in preventing catastrophe.

Understanding Biological Weapons in Scientific Terms

Biological weapons are not a vague or abstract concept. They are defined as the deliberate use of biological agents, such as microorganisms or toxins derived from living organisms, to cause disease or death in humans, animals, or plants for hostile purposes. Their power lies not only in lethality, but in their capacity for spread, uncertainty, and psychological terror. Unlike conventional weapons, biological agents can be invisible, delayed in effect, and difficult to attribute.

From a scientific perspective, the development of a biological weapon is extraordinarily complex. It involves selecting or modifying a biological agent, ensuring it remains viable, controlling its behavior in real-world environments, and delivering it in a way that achieves the intended effect. Each of these steps presents enormous technical challenges. Biology is not an exact or predictable machine. Living systems are shaped by evolution, randomness, and environmental context, which makes precise control difficult even for legitimate medical or research purposes.

Internationally, biological weapons are prohibited under the Biological Weapons Convention, which bans their development, production, and stockpiling. This treaty reflects a global consensus that such weapons are uniquely dangerous and morally unacceptable. As a result, legitimate biological research operates within strict ethical and regulatory frameworks designed to prevent misuse.

Any discussion of AI and biological weapons must begin with this reality: biological weapon development is not a simple matter of design, but a deeply constrained, high-risk endeavor requiring human intention, resources, and sustained effort.

What Artificial Intelligence Really Is and Is Not

Artificial intelligence is often portrayed as an autonomous entity capable of independent thought and action. In scientific reality, AI is a collection of computational methods designed to perform specific tasks by learning from data. Modern AI systems, including machine learning models, do not possess intentions, desires, or moral understanding. They do not initiate goals on their own. They respond to inputs, optimize objectives defined by humans, and operate within the boundaries of their training and deployment.

In the biological sciences, AI is increasingly used for beneficial purposes. It helps researchers analyze genetic data, predict protein structures, model disease spread, and accelerate drug discovery. These applications rely on the ability of algorithms to detect patterns in vast datasets that would be impossible for humans to analyze manually. Importantly, these systems function as tools that assist human scientists rather than replacing them.

The fear that AI could “create” a biological weapon often arises from a misunderstanding of this tool-like nature. AI does not independently conduct experiments, culture organisms, or deploy biological agents. It cannot act in the physical world without human mediation. Any harmful application of AI in biology would therefore depend on deliberate misuse by people who already possess access to biological knowledge and infrastructure.

The Appeal of the Dark Narrative

The idea of AI-generated biological weapons captures public imagination because it combines two sources of anxiety: the fear of uncontrollable technology and the fear of invisible, uncontrollable disease. Popular culture has long explored scenarios in which scientific progress outpaces ethical restraint, leading to unintended or malicious consequences. AI, with its rapid development and opaque decision-making processes, has become a natural focal point for such concerns.

This narrative is emotionally powerful, but it often obscures the realities of scientific practice. It suggests that knowledge itself is dangerous, rather than the ways in which knowledge is used. It also risks diverting attention from more immediate and plausible threats, such as human-led misuse of existing biological tools or the erosion of public health systems.

A scientifically grounded discussion must therefore resist the temptation to anthropomorphize AI or treat it as an independent villain. Instead, it must examine how AI could realistically intersect with biological research, where vulnerabilities might exist, and how those vulnerabilities can be addressed.

AI in Biological Research: Capabilities and Constraints

AI has demonstrated remarkable capabilities in analyzing biological data. It can identify patterns in genetic sequences, simulate aspects of molecular interactions, and generate hypotheses for further investigation. These functions can dramatically accelerate research in medicine and biotechnology. However, they also operate within clear constraints.

Biological data are noisy, incomplete, and context-dependent. AI models trained on such data inherit these limitations. Predictions made by AI require experimental validation, often through labor-intensive and highly regulated laboratory work. In legitimate research settings, this validation process acts as a safeguard, ensuring that computational insights do not translate directly into real-world actions without scrutiny.

Moreover, biological systems are shaped by emergent properties that cannot be fully captured by existing models. Small changes at the molecular level can have unpredictable effects at the level of organisms or populations. This unpredictability makes the notion of precisely designing a harmful biological agent through AI alone highly implausible.

AI can suggest possibilities, but it cannot guarantee outcomes. This limitation is crucial when considering fears about biological weapons, which require not just theoretical design but reliable, repeatable effects under diverse conditions.

Dual-Use Research and the Ethical Tension

One of the most serious and legitimate concerns surrounding AI in biology lies in the concept of dual-use research. Dual-use research refers to scientific work that is intended for beneficial purposes but could also be misused for harmful ends. This tension is not new. Long before AI, advances in microbiology, genetics, and chemistry raised similar concerns.

AI intensifies this tension by accelerating research and lowering certain technical barriers. Tools that help design medical interventions could, in theory, be misapplied by malicious actors. However, this risk exists within a broader social and institutional context. Scientific research does not occur in isolation. It is embedded in ethical review processes, funding structures, professional norms, and legal regulations.

Responsible scientists are trained to recognize dual-use risks and to mitigate them through transparency, oversight, and collaboration with regulatory bodies. AI does not remove this responsibility. If anything, it heightens the need for ethical literacy and governance within the scientific community.

Can AI Lower the Barrier to Biological Harm?

A central question in the debate is whether AI significantly lowers the barrier to creating biological weapons. From a scientific standpoint, the answer is nuanced. AI can make certain types of analysis faster and more accessible, but it does not eliminate the need for expertise, infrastructure, and intent.

The most dangerous aspects of biological weaponization are not computational. They involve cultivation, stabilization, dissemination, and evasion of detection, all of which require physical resources and tacit knowledge acquired through experience. These elements are difficult to automate and tightly controlled in most countries.

Furthermore, the misuse of AI-generated insights would still require a human decision to act maliciously. AI cannot cross ethical boundaries on its own. The barrier that matters most is not technological, but moral and institutional.

The Role of Human Agency

At the core of every credible threat scenario involving AI and biological weapons lies human agency. Humans define the goals, select the tools, interpret the results, and decide how to act. AI amplifies human capabilities, but it does not replace human responsibility.

History demonstrates that technological harm arises not from tools themselves, but from the contexts in which they are used. The same biological knowledge that enables vaccines and treatments can be misused in the absence of ethical restraint. AI does not fundamentally change this dynamic. It accelerates processes, but it does not create intent.

Recognizing this fact shifts the focus of prevention from controlling technology alone to strengthening norms, education, and institutions that guide human behavior. It also underscores the importance of fostering a scientific culture that values responsibility as highly as innovation.

Safeguards in Science and Technology

Modern biological research is governed by multiple layers of safeguards designed to prevent misuse. These include ethical review boards, regulatory agencies, international agreements, and professional codes of conduct. AI-related research increasingly falls under similar scrutiny, particularly when it intersects with sensitive domains.

Technical safeguards are also evolving. Researchers are developing methods to limit the misuse of AI models, such as controlled access, monitoring of usage patterns, and alignment of systems with ethical guidelines. While no safeguard is perfect, the combination of technical, legal, and cultural barriers significantly reduces the likelihood of catastrophic misuse.

Importantly, these safeguards are most effective when they are global. Biological threats do not respect national boundaries, and neither does scientific knowledge. International cooperation remains essential for monitoring risks and responding to emerging challenges.

Misinformation and the Amplification of Fear

Public fear about AI and biological weapons is often fueled by misinformation and speculative scenarios presented without context. Sensational claims can erode trust in science and distract from real issues, such as the need for robust public health infrastructure and transparent governance.

A scientifically accurate understanding of AI’s capabilities helps counter these fears. It reveals that while risks exist, they are not inevitable or uncontrollable. Fear-based narratives may attract attention, but they rarely contribute to effective solutions.

Clear communication between scientists, policymakers, and the public is therefore crucial. Explaining what AI can and cannot do fosters informed discussion rather than panic.

The Ethical Responsibility of AI Developers

Developers of AI systems bear a significant ethical responsibility, particularly when their tools are applied in sensitive domains like biology. This responsibility includes anticipating potential misuse, engaging with ethicists and policymakers, and designing systems with safety in mind.

Ethical responsibility is not a constraint on innovation, but a condition for sustainable progress. AI that accelerates medical discovery can save lives, but only if it is developed and deployed within a framework that prioritizes human well-being.

Education plays a key role in this process. Training scientists and engineers to think critically about the societal implications of their work helps ensure that technological power is matched by moral awareness.

Global Governance and the Future of Risk

As AI and biotechnology continue to advance, questions of governance will become increasingly important. No single nation or institution can manage these risks alone. International dialogue and cooperation are essential for setting norms, sharing best practices, and responding to potential threats.

Global governance does not mean stifling research. It means creating shared expectations about acceptable behavior and mechanisms for accountability. In the context of biological weapons, existing international frameworks provide a foundation that can be adapted to address AI-related concerns.

The future of risk management lies not in halting technological progress, but in guiding it wisely. AI will continue to shape biology, just as previous tools have shaped science. The challenge is to ensure that this shaping serves humanity rather than endangers it.

Why AI Is More Likely to Prevent Than Create Biological Weapons

An often-overlooked aspect of this discussion is the potential for AI to reduce biological risks rather than increase them. AI can enhance disease surveillance, improve early warning systems, and accelerate the development of countermeasures. It can help identify vulnerabilities in public health systems and model the spread of outbreaks, enabling faster and more effective responses.

These preventive applications reflect a broader truth about technology: its impact depends on how it is directed. When aligned with public health and ethical goals, AI becomes a powerful ally against biological threats.

Focusing exclusively on worst-case scenarios obscures these positive possibilities. A balanced assessment recognizes both risks and benefits, and seeks to maximize the latter while minimizing the former.

The Psychological Dimension of Fear

Fear surrounding AI and biological weapons also reflects deeper anxieties about loss of control. Biology touches life itself, and AI challenges traditional notions of human mastery over tools. Together, they evoke a sense of vulnerability that can be unsettling.

Understanding this psychological dimension is important for constructive dialogue. Fear is not irrational, but it can become counterproductive if it leads to paralysis or hostility toward science. Addressing fear requires empathy, transparency, and education, not dismissal.

By engaging openly with concerns and grounding discussions in evidence, scientists and communicators can help transform fear into informed vigilance.

A Realistic Assessment of the Dark Potential

The question of whether AI can create a biological weapon does not admit a simple yes or no answer. AI can contribute to biological research in ways that, if misused, could pose risks. However, it cannot independently design, build, or deploy biological weapons. Such outcomes would require human intent, access, and sustained effort in defiance of ethical and legal norms.

The dark potential often attributed to AI lies less in the technology itself than in the choices made by those who wield it. This insight places responsibility where it belongs: on human societies, institutions, and values.

Recognizing this does not mean complacency. It means focusing on realistic threats and effective safeguards rather than hypothetical doomsday scenarios.

Science, Responsibility, and the Path Forward

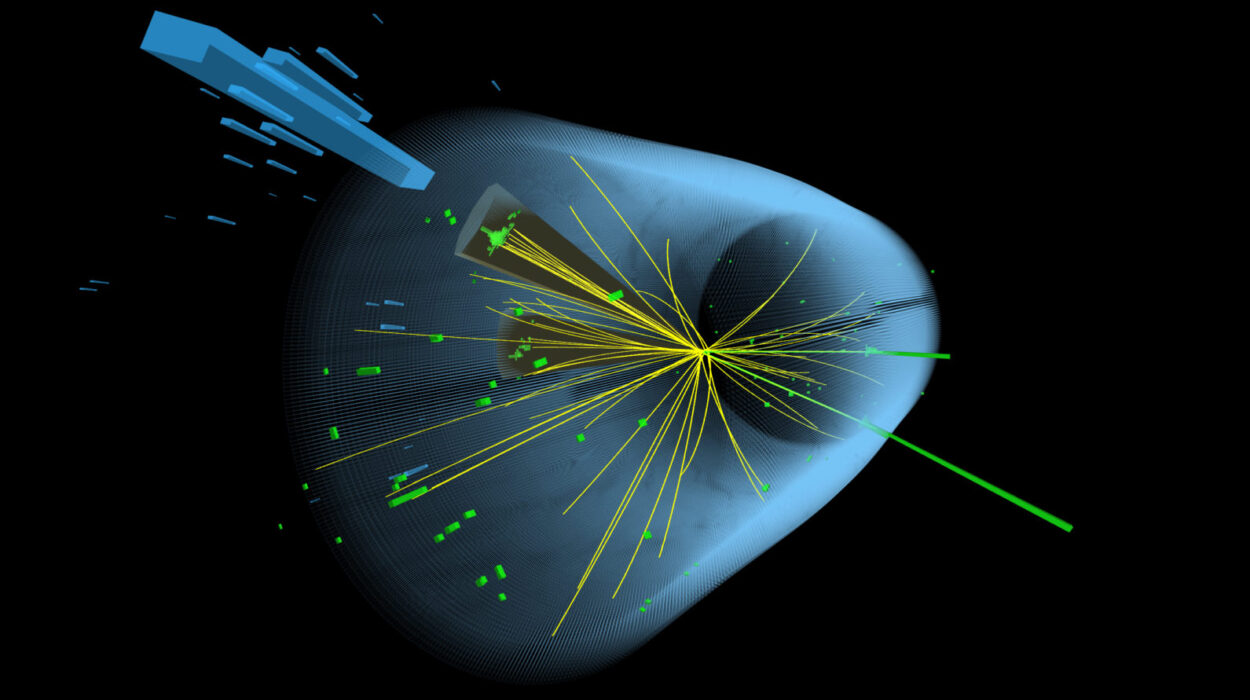

Physics, biology, and artificial intelligence share a common heritage as tools for understanding and shaping the world. They reflect humanity’s capacity for creativity and reason. At the same time, they demand humility and responsibility.

The fear that AI could create biological weapons is a reminder of the stakes involved in scientific progress. It challenges researchers, policymakers, and citizens to think carefully about how knowledge is generated and used.

The path forward lies in strengthening ethical norms, investing in oversight, and fostering a culture of responsibility within science and technology. It lies in recognizing that tools do not determine outcomes on their own; people do.

Conclusion: Power Without Intention Is Not a Weapon

AI is powerful, but it is not purposeful. Biology is complex, but it is not easily controlled. The convergence of these fields raises legitimate questions, but also reveals the resilience of existing safeguards and the central role of human judgment.

Can AI create a biological weapon? Not by itself, and not in the way popular imagination often suggests. The real danger lies not in machines acting alone, but in humans choosing to abandon ethical constraints. Conversely, the real hope lies in using AI to deepen understanding, strengthen health systems, and reduce the very risks that inspire fear.

In the end, the story of AI and biological weapons is not a story about inevitable doom. It is a story about responsibility, governance, and the enduring capacity of science to serve humanity when guided by wisdom rather than fear.