From Earth, the region of space known as RXC J0032.1+1808 looks calm, almost unremarkable. It sits quietly in the nearby universe, its galaxies bound together by gravity, glowing faintly across millions of light years. But when astronomers pointed one of the world’s most powerful instruments toward it, the calm illusion began to fracture. What they found was not a peaceful gathering of galaxies, but the aftermath of a colossal cosmic collision still unfolding in slow motion.

Using the Keck Observatory’s DEep Imaging Multi-Object Spectrograph, known as DEIMOS, astronomers uncovered evidence that this galaxy cluster is in the middle of a major merger. The discovery, presented in a research paper published December 16 on the pre-print server arXiv, reveals RXC J0032.1+1808 as a system shaped by violence on a scale almost impossible to imagine.

When Gravity Brings Giants Together

Galaxy clusters are the largest structures in the universe held together by gravity. Each can contain hundreds or even thousands of galaxies, along with vast reservoirs of hot gas and unseen dark matter. They are not born fully formed. Instead, they grow over time, pulling in smaller groups and merging with other clusters in slow, titanic encounters that can last hundreds of millions of years.

Because of this, galaxy clusters act like cosmic laboratories. By watching how they collide and combine, astronomers can learn how galaxies evolve, how matter behaves under extreme conditions, and how the universe itself is structured. Merging clusters are especially valuable because they expose physical processes that remain hidden in calmer systems.

RXC J0032.1+1808 is one such laboratory. First identified at visible wavelengths in 1965 under the name ZwCl 0029.5+1750, it is a rich cluster with an estimated mass of about 1.1 quadrillion times that of the Sun. For decades, it was simply one more entry in astronomical catalogs. But its true nature only emerged once astronomers looked deeper.

Looking Deeper with DEIMOS

A team of astronomers led by David Wittman of the University of California, Davis, decided to examine RXC J0032.1+1808 more closely using DEIMOS. This instrument is designed to collect detailed spectral information from multiple objects at once, making it particularly powerful for studying complex systems like galaxy clusters.

What they saw immediately challenged earlier impressions. Optical observations had shown an elongated structure, suggesting a single cluster stretched out across space. But the DEIMOS observations told a different story, one written not in visible light but in X-rays.

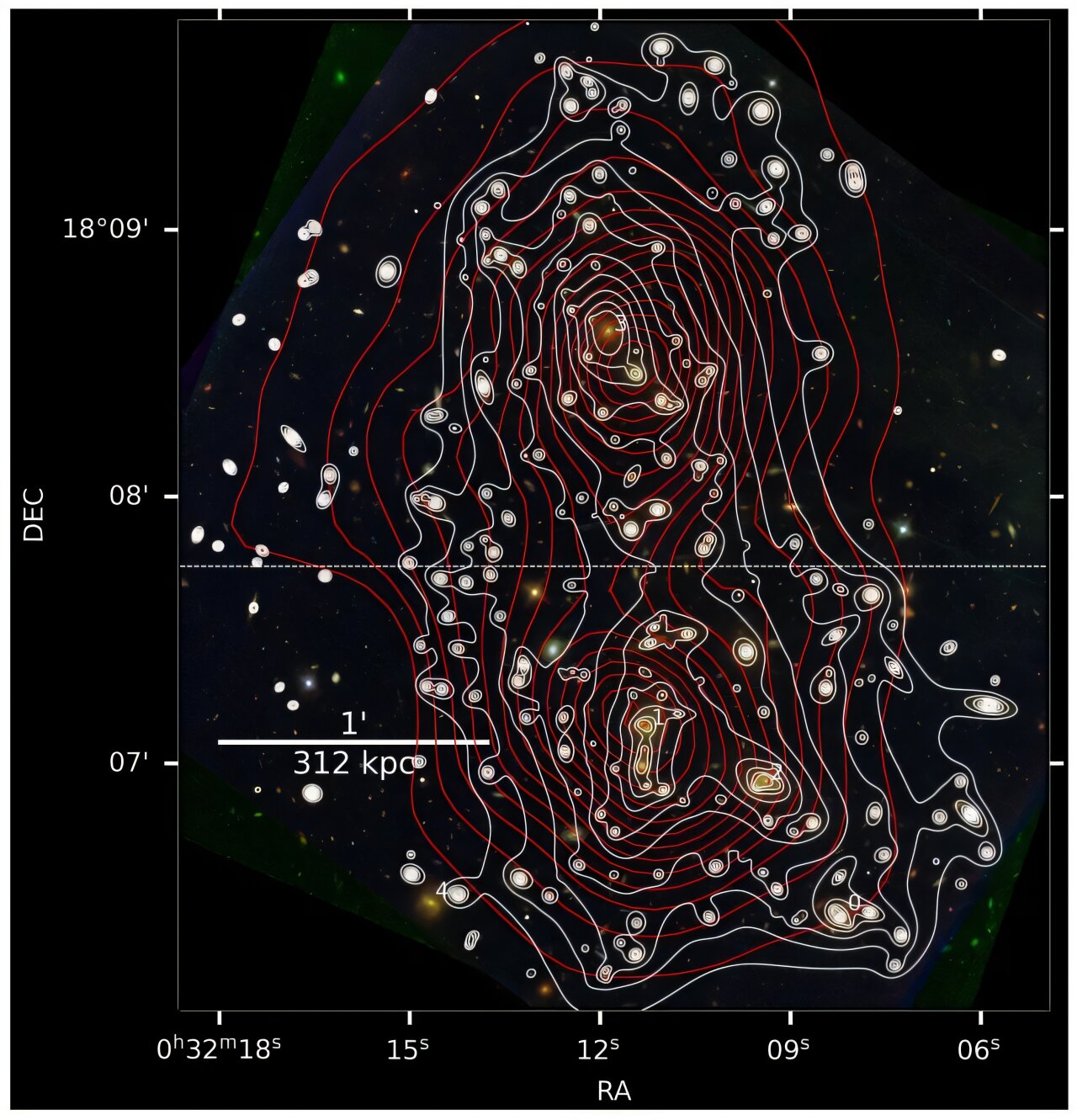

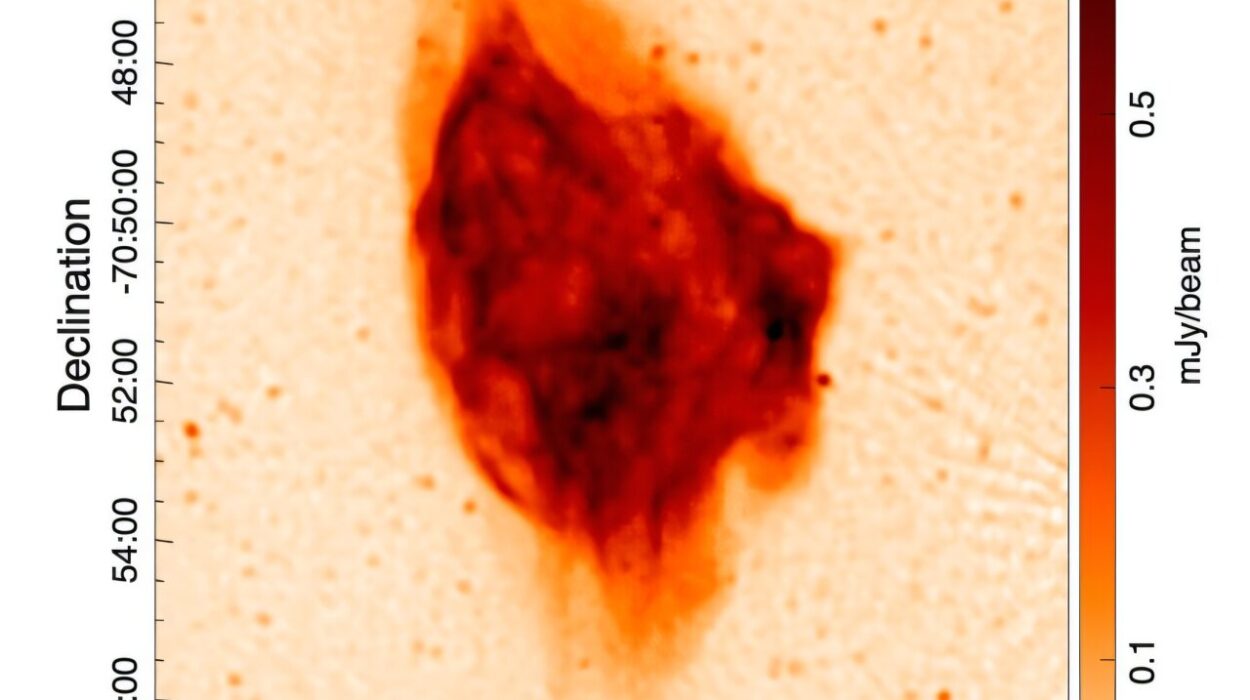

“We find that its X-ray morphology is bimodal, suggesting that it is in the process of merging,” the researchers write in the paper.

That single sentence captures the heart of the discovery. Instead of one smooth concentration of hot gas, the X-ray data revealed two distinct peaks. These peaks are separated by about 1.3 million light years and aligned almost perfectly along a northward direction. Such bimodality is a classic sign that two massive clusters are colliding and have not yet settled into a single, unified structure.

Reading the Aftermath of a Cosmic Collision

The presence of two X-ray peaks is not just a snapshot of structure; it is a clue to timing. Galaxy cluster mergers follow a sequence. First, two clusters approach. Then comes the pericenter, the moment of closest passage, when their cores swing past each other and the collision reaches its most violent phase. After that, the system enters a long post-collision period as gravity slowly pulls the pieces back together.

The DEIMOS data, combined with the presence of a radio relic identified by previous observations, suggest that RXC J0032.1+1808 is being seen after that critical moment. The astronomers estimate that the cluster is observed approximately 395 to 560 million years after the first pericenter.

In human terms, this would be like arriving at the scene of a massive earthquake centuries after it happened, when the ground is still shifting and scars remain visible, but the initial shock has passed. The galaxies themselves move relatively untouched through the collision, but the hot gas and dark matter reveal where the real drama occurred.

A Collision That Happened Sideways

One of the most intriguing findings from the study comes from measuring how fast the two subclusters are moving relative to each other along our line of sight. The researchers found that this relative velocity is surprisingly small, about 76 kilometers per second.

This low value suggests that the merger is not happening head-on toward or away from Earth. Instead, it is occurring primarily in the plane of the sky, meaning we are seeing it from the side. This orientation is especially valuable for scientists because it allows clearer separation of structures that might otherwise overlap and blur together in observations.

A sideways collision lets astronomers better trace where the gas, galaxies, and dark matter have gone since the impact. It turns RXC J0032.1+1808 into a natural experiment, frozen in a moment where the effects of a high-speed cosmic encounter can still be studied in detail.

Why Astronomers Care About Merging Clusters

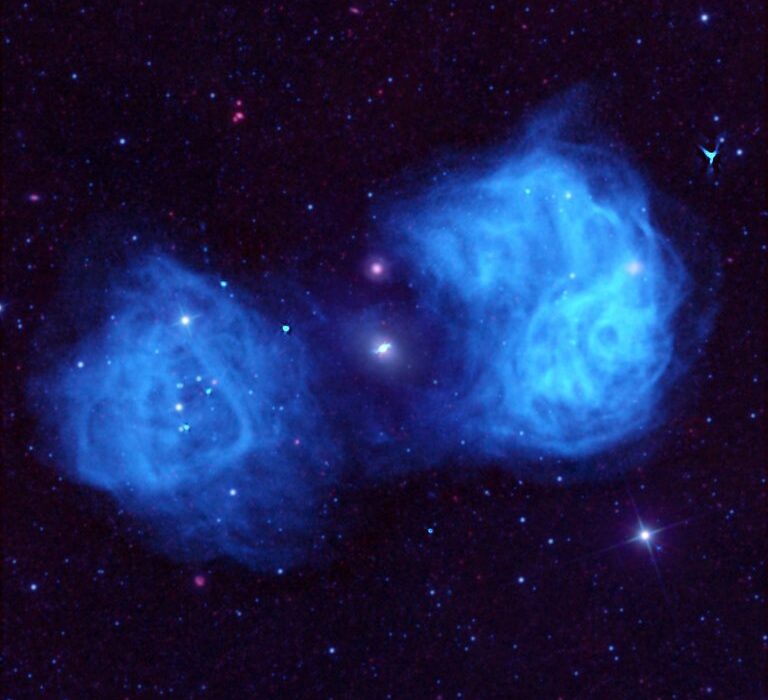

Merging galaxy clusters are not just visually dramatic; they are scientifically rich. They offer rare opportunities to study shock fronts and cold fronts in the diffuse gas that fills the space between galaxies. These features reveal how energy is transferred on enormous scales and how matter behaves under extreme pressure and temperature.

They also help scientists investigate how cosmic rays are accelerated within clusters and explore the self-interaction properties of dark matter. Because dark matter does not emit light, its behavior can only be inferred through its gravitational effects and how it separates from visible matter during collisions.

RXC J0032.1+1808, with its clear bimodal structure and well-constrained merger geometry, stands out as an especially promising case. The authors conclude that it represents a major, rich, and bimodal merger, making it an excellent laboratory for studying the physics of merging clusters and the behavior of dark matter during high-velocity collisions.

Why This Discovery Matters

This research matters because it turns a distant, seemingly ordinary cluster into a window on some of the universe’s deepest mysteries. By identifying RXC J0032.1+1808 as a system caught in the aftermath of a massive merger, astronomers have found a place where theory can be tested against reality.

Here, the invisible becomes partially visible. The motions of galaxies, the glow of hot gas in X-rays, and the subtle clues left by a past collision combine to tell a story written across millions of light years and hundreds of millions of years. Each detail helps scientists refine their understanding of how large-scale structures form and evolve.

In the end, RXC J0032.1+1808 reminds us that the universe is not static. Even the largest structures we know are shaped by motion, impact, and change. Thanks to careful observation and patient analysis, astronomers have learned to read these slow, colossal events, turning faint signals from deep space into narratives about how the cosmos builds itself, one collision at a time.

More information: David Wittman et al, A Very Rich Bimodal Galaxy Cluster Merger: RXC J0032.1+1808, arXiv (2025). DOI: 10.48550/arxiv.2512.14945