In 2015, nearly every nation on Earth signed the Paris Agreement, a historic pact to limit global warming to “well below 2°C,” ideally 1.5°C. It was a moment of hope, a collective pledge to safeguard humanity’s future. Yet, almost a decade later, that promise is slipping through our fingers. Global emissions continue to rise, national pledges remain insufficient, and the gap between what is needed and what is delivered grows wider each year.

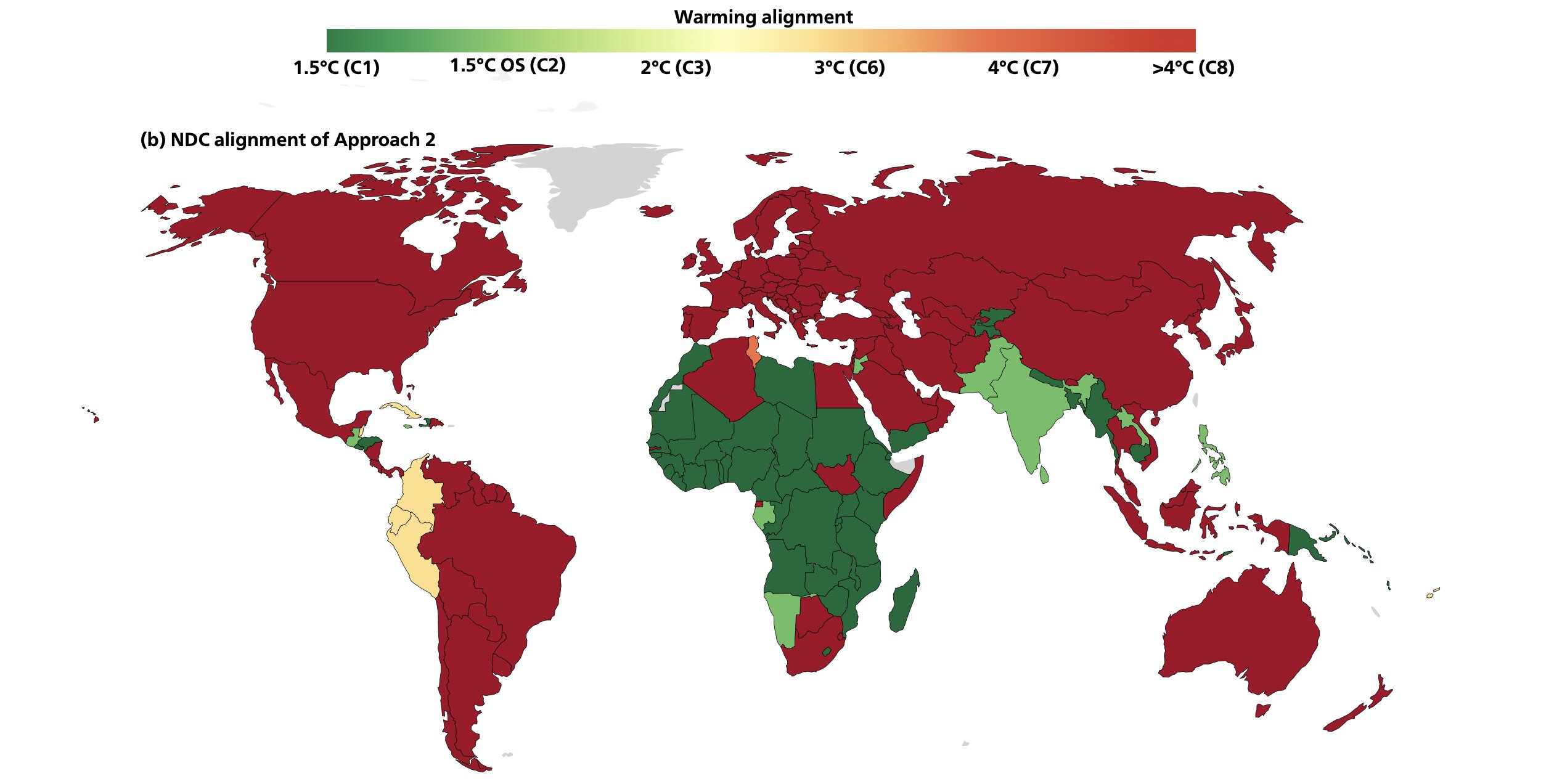

The truth is sobering: climate action is falling behind. But a new study led by researchers from Utrecht University reveals that the problem is not just a lack of ambition—it is also how ambition and fairness have been calculated. Their work uncovers a hidden bias that favors the biggest polluters while penalizing the most vulnerable nations. And that finding could reshape the entire global effort to combat climate change.

When Fairness Isn’t Fair

The study, published in Nature Communications on 3 September, challenges the way “fair shares” of climate action have been assessed until now. Traditionally, countries’ responsibilities have been calculated from shifting baselines of rising emissions. This approach, researchers argue, rewards high emitters by allowing them to start later and do less, while placing heavier burdens on nations that have contributed little to the problem.

“Previous studies assessing countries’ climate ambition share a feature that rewards high emitters at the expense of the most vulnerable ones,” explains lead researcher Yann Robiou du Pont.

This bias has real-world consequences. It means that countries most responsible for the crisis—wealthy, industrialized nations—have been shielded from making the steep cuts they owe. Meanwhile, poorer countries, often on the front lines of climate disasters, are left with a heavier share of the global burden.

A New Baseline for Responsibility

The Utrecht team proposes a radical shift. Instead of starting from today’s emissions levels, they calculate ambition and fairness directly from countries’ historical responsibility and their financial capacity to act.

This new baseline is uncompromising. It recognizes that wealthy nations have burned through the lion’s share of the global carbon budget, and therefore must lead with deep, immediate cuts. The United States, Australia, Canada, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates emerge as countries with the greatest “ambition gap”—a measure of how far current pledges fall short of what fairness demands.

The results are stark. If applied, this approach would force some countries to abruptly change course, slashing emissions far more aggressively than their current trajectories. But the method also recognizes reality: since these reductions cannot be achieved locally alone, wealthy nations would need to finance mitigation in poorer countries.

This isn’t charity—it is climate debt. It is about paying for the damage already caused, and about enabling global cooperation to keep the Paris goals alive.

The Role of Climate Courts

The implications of this research extend far beyond academic debate. Increasingly, courts are stepping in where politics falters. From local lawsuits to international tribunals, judges are being asked to decide whether governments’ climate pledges are fair, sufficient, and lawful.

One of the most striking examples is the KlimaSeniorinnen case before the European Court of Human Rights, where senior Swiss women successfully argued that insufficient climate action violated their human rights. The court agreed: inadequate policies are not just political failures—they are legal breaches.

Fair-share assessments like the one from Utrecht are central to these cases. If the metrics themselves are biased, then justice is undermined. By correcting the bias, courts gain a clearer, more honest tool for holding nations accountable.

This judicial role is expanding. On July 23, 2025, the International Court of Justice issued a landmark advisory opinion affirming that states have a legal obligation under international law to prevent “significant harm” to the climate system. The ruling underscored that inaction is no longer a political option—it is a violation of global responsibility.

“This strengthens and underscores the growing role of courts in enforcing climate justice,” says Robiou du Pont.

Paying the Debt: A Moral and Practical Imperative

At its core, this debate is not only about carbon numbers and percentages—it is about justice. Wealthy nations industrialized early, reaping centuries of economic benefits while pumping vast amounts of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. Poorer nations, by contrast, contributed little to the crisis but now suffer some of its worst consequences: rising seas, deadly heatwaves, droughts, and crop failures.

To call for “fair shares” is to demand that those who caused the most harm and have the greatest resources take the lead in repairing the damage. It means that climate finance—funding clean energy, adaptation, and loss-and-damage programs in vulnerable countries—is not generosity. It is repayment.

Without this fairness, the Paris goals will remain out of reach. The world will stumble toward catastrophic warming. But with it, global cooperation becomes possible, trust is rebuilt, and ambition rises across all nations.

The Path Forward

The Utrecht study delivers a clear message: the time for half-measures is over. Immediate responsibility must replace delayed obligations. High emitters cannot be rewarded for their past inaction, and vulnerable nations cannot be asked to shoulder the weight of a crisis they did not create.

Fairness is not an obstacle to ambition—it is the key to unlocking it. A fairer system of responsibility compels wealthy nations to cut deeper, faster, and to support global action through finance and technology transfer. This does not only meet the moral imperative long voiced by climate justice advocates; it also offers the most practical route to achieving the Paris Agreement’s targets.

The challenge is immense. The politics are messy. But the principle is simple: the fight against climate change will succeed only if it is fair.

As the courts remind us, this is not just about science or policy. It is about human rights, global responsibility, and the future of life on Earth.

And the time to act is not tomorrow, or in 2030. It is now.

More information: Effect of discontinuous fair-share emissions allocations immediately based on equity., Nature Communications (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-62947-9