More than 10,000 years ago, Earth began to thaw. The last ice age — a time when colossal glaciers blanketed much of the Northern Hemisphere — was coming to an end. Across the continents, rivers swelled, coastlines shifted, and the frozen silence of millennia gave way to the sound of rushing meltwater. Humanity, just learning to farm and settle, was witnessing one of the greatest natural transformations in history.

For decades, scientists believed that Antarctica, Earth’s vast southern ice fortress, played the starring role in this ancient drama of rising seas. Its enormous ice sheets, it was thought, released torrents of meltwater into the global ocean, raising sea levels and reshaping coastlines around the world. But a new study led by Tulane University and published in Nature Geoscience has turned that long-held belief on its head.

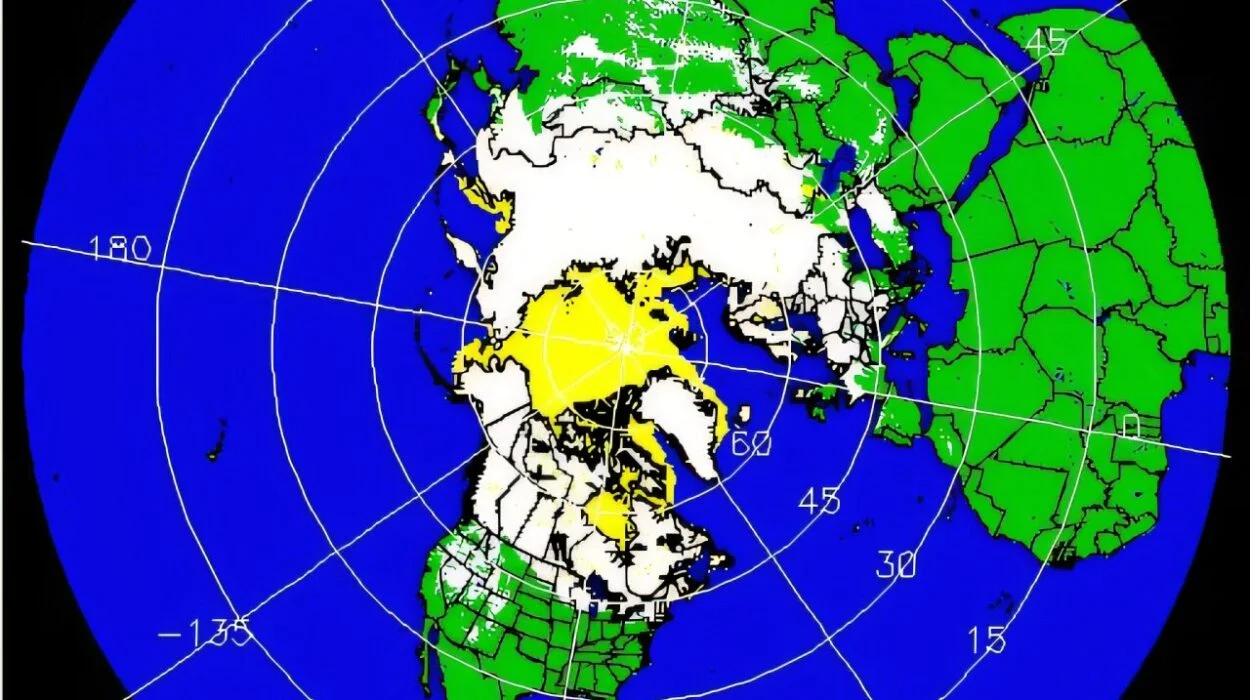

The findings reveal that it was not Antarctica, but the melting ice sheets of North America that were the true giants behind the post–ice age flood. Between 8,000 and 9,000 years ago, retreating North American ice sheets — remnants of the massive Laurentide and Cordilleran glaciers — caused more than 30 feet (about 10 meters) of global sea-level rise. That’s the height of a three-story building, added to the oceans in just a few centuries.

A New Chapter in Earth’s Ice Age Story

“This requires a major revision of the ice melt history during this critical time interval,” said Torbjörn Törnqvist, Vokes Geology Professor at Tulane and co-author of the study. His words underscore a seismic shift in scientific understanding — one that rewrites how our planet transitioned from a frozen world to the one we know today.

The research shows that the freshwater released by the melting North American ice was far greater than anyone had realized. Vast volumes of it poured into the North Atlantic Ocean, altering its salinity and potentially influencing the powerful ocean currents that regulate Earth’s climate. These currents, particularly the Gulf Stream, act as the planet’s thermal engine — transporting warm tropical waters northward and keeping regions like Northwestern Europe much milder than their latitude should allow.

For decades, climate scientists have worried that this delicate balance could be disrupted by today’s melting Greenland Ice Sheet, which, like its ancient North American counterpart, drains into the North Atlantic. The fear has been that an influx of fresh meltwater could weaken or even shut down the Gulf Stream, triggering abrupt cooling in Europe and upheavals in global weather patterns.

Yet, the new Tulane findings paint a more complex picture. If the Gulf Stream system survived the colossal floods of 9,000 years ago, it might be more resilient than modern models suggest — though not necessarily invulnerable.

“Clearly, we don’t fully understand yet what drives this key component of the climate system,” Törnqvist cautioned. His words carry both reassurance and warning: Earth’s climate machine has endured enormous shocks before, but the rules of that endurance remain elusive.

The Hidden Record Beneath the Delta

Reconstructing sea levels from thousands of years ago is among the most challenging tasks in Earth science. Much of the evidence lies buried deep beneath layers of sediment or submerged beneath coastal waters. For the Tulane team, the breakthrough came not in the icy Arctic or the frozen Antarctic, but in the heart of Louisiana — across the Mississippi River from New Orleans.

There, former Tulane postdoctoral researcher Lael Vetter made a remarkable discovery: deeply buried layers of ancient marsh sediments, preserved like pages in a time capsule. By carefully analyzing these layers and using carbon-14 dating, Vetter and her colleagues were able to reconstruct sea-level changes that stretched back more than 10,000 years — farther than most previous studies had ever reached.

Those ancient sediments told a story of rapid change. Sea levels rose faster than could be explained by melting Antarctic ice alone. Something massive, closer to home, was adding water to the world’s oceans — and all evidence pointed northward.

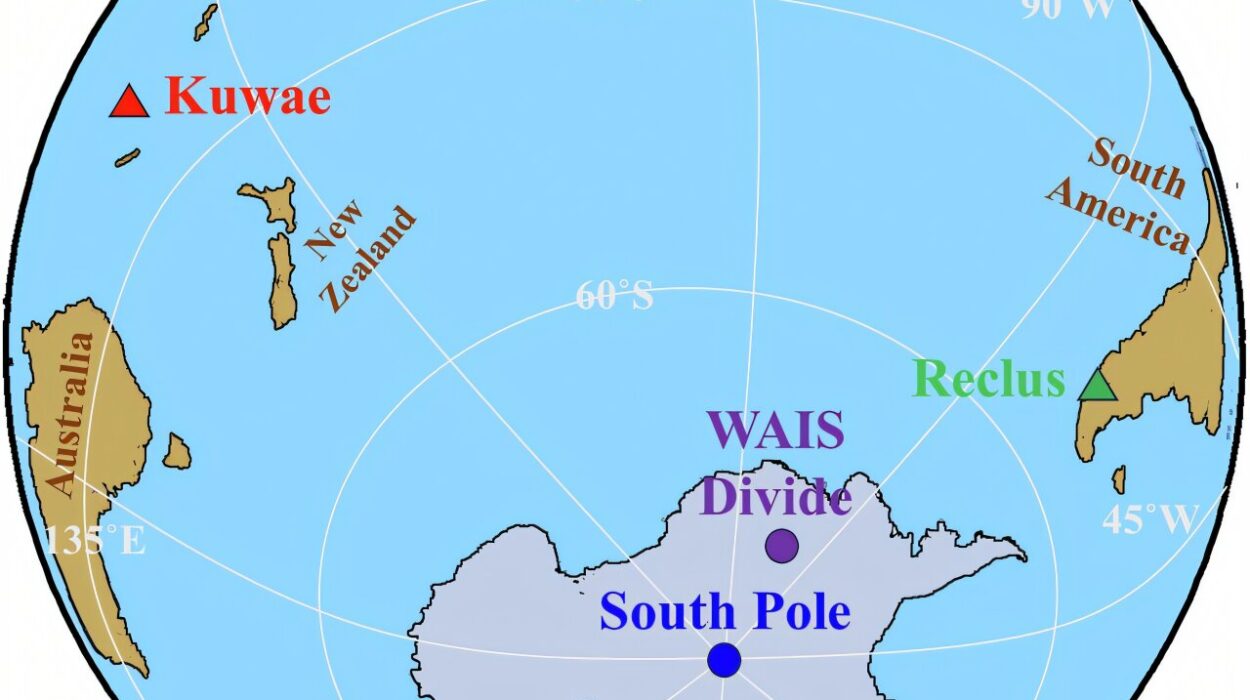

Building on Vetter’s work, Tulane Ph.D. student Udita Mukherjee expanded the investigation to a global scale. She compared the Mississippi Delta data with records from Europe and Southeast Asia. The result was striking: regional differences in sea-level rise rates that could only be explained if North America’s ice sheets had melted far more rapidly and extensively than anyone had thought.

Rethinking Earth’s Climate Resilience

“This research provides a stark reminder of the complexities of our climate system and melting ice sheets,” said Mukherjee, now a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Hong Kong. Her words capture the essence of what makes this study groundbreaking: it not only revises the story of the past but reshapes how we think about the future.

The new findings suggest that the climate system of the early Holocene — the epoch following the last ice age — was able to absorb immense pulses of freshwater without completely collapsing ocean circulation. That resilience could be a hopeful sign, indicating that Earth’s climate machinery is not as fragile as some models predict.

However, the past also offers a cautionary tale. The planet 9,000 years ago was far cooler and less human-influenced than it is today. Today’s ice melt, driven by greenhouse gas emissions and industrial-scale warming, is happening much faster. The balance between resilience and collapse may be far thinner in our modern world.

If Greenland’s ice sheet continues to melt at accelerating rates, it could send vast volumes of freshwater into the North Atlantic — echoing, in a way, the ancient floods from North America. But unlike the natural warming that ended the last ice age, today’s changes are being driven by human hands, in a world already strained by climate extremes.

Lessons from a Global Perspective

One of the most profound aspects of the Tulane study is its global reach. Mukherjee emphasized that the research would not have been possible without combining data from multiple continents. “Broadening our focus beyond North America and Europe to include valuable high-quality data from Southeast Asia was critical for this study,” she said. “By embracing a truly global perspective in climate studies, we can enhance our understanding and work together toward a sustainable future.”

This international approach represents a new era in Earth science — one that recognizes climate as a planetary system, not a regional problem. The fingerprints of melting ice in North America were found in the sediments of Asia. The rhythm of ancient sea levels was recorded in the marshes of Louisiana and the coasts of Europe. The planet’s systems are inseparable, its histories intertwined.

Echoes of the Past, Warnings for the Future

The Tulane findings remind us that Earth is a dynamic, interconnected organism — one that remembers every change written in its rocks, sediments, and seas. The end of the last ice age was not just an ancient chapter; it was a rehearsal for the transformations unfolding today.

If the melting of North American ice could raise global sea levels by over 30 feet, imagine what could happen if modern ice sheets — in Greenland and Antarctica combined — were to collapse under the heat of the 21st century. The world’s great coastal cities, from New York to Mumbai, from London to Dhaka, would face a future of rising tides and shifting shorelines.

Yet within the story of ancient ice lies a message of resilience and responsibility. The Gulf Stream survived the floods of prehistory. Earth’s systems adapted, adjusted, and endured. But they did so over thousands of years — a timescale that gives humanity no comfort in a world changing by decades.

Science, at its best, does not simply reveal facts; it restores perspective. It shows us that our planet has faced immense challenges before — and that its fate now, more than ever, depends on human choices.

The River Beneath Our Feet

In the muddy sediments of the Mississippi Delta, a handful of scientists have uncovered not just a geological record but a living reminder of Earth’s power and vulnerability. Each layer of ancient marsh, each carbon-dated grain, tells of an age when ice met ocean and the world transformed.

Their work reminds us that even the most unassuming landscapes — a riverbank, a swamp, a buried wetland — can hold the keys to understanding our planet’s past and guiding its future.

In the story of the melting North American ice sheets, we find both awe and warning. The Earth we inherit is shaped by the Earth that was. And as the ice melts once again, it is our turn to decide what the next chapter will be.

More information: Sea-level rise at the end of the last deglaciation dominated by North American ice sheets, Nature Geoscience (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41561-025-01806-0.