Value is a curious human invention. We assign it to objects not merely because they are beautiful or useful, but because they are rare, difficult to obtain, or uniquely powerful in what they allow us to do. Nowhere is this more evident than in the materials that command astonishing prices when measured gram for gram. Some of these substances are precious because nature made them scarce over billions of years. Others are expensive because human ingenuity struggles to create them, atom by atom, under extreme conditions. A few are valuable not because they glitter or endure, but because they briefly exist at the edge of what physics allows.

This is not a list driven by luxury alone. Diamonds and gold, iconic as they are, do not always top the chart when value is measured by mass. Instead, the most expensive materials often come from laboratories, particle accelerators, or the violent furnaces of stars. Their worth lies in the extraordinary effort required to obtain them and the profound scientific knowledge they embody.

What follows is a scientifically grounded exploration of the eight most expensive materials on Earth, considered gram for gram. Each one tells a story about scarcity, technology, and humanity’s desire to understand and shape the universe.

1. Antimatter

Antimatter stands alone at the summit of value, unmatched by any naturally occurring substance. Gram for gram, it is the most expensive material humans have ever produced, not because it is useful in everyday life, but because creating it pushes physics and engineering to their absolute limits.

Antimatter is not a speculative idea or science fiction fantasy. It is a real and well-understood consequence of modern physics. For every type of particle that makes up ordinary matter, there exists a corresponding antiparticle with the same mass but opposite electric charge and other quantum properties. When matter and antimatter meet, they annihilate each other, converting their mass entirely into energy according to Einstein’s equation E = mc².

The challenge is that antimatter does not exist naturally on Earth in usable quantities. When it is produced—typically in high-energy particle accelerators—it must be carefully trapped using electromagnetic fields, because any contact with ordinary matter leads to instant annihilation. Even storing a few thousand atoms requires sophisticated equipment and extreme precision.

The energy cost of producing antimatter is staggering. Particle accelerators must operate for long periods, consuming enormous amounts of electricity, to generate minuscule quantities of antiparticles. Most of the energy put into the process is lost, making antimatter production profoundly inefficient by any practical standard.

Its theoretical potential, however, is immense. Antimatter offers the highest energy density of any known substance, far exceeding chemical fuels and even nuclear reactions. This has led to speculation about its use in deep-space propulsion or medical imaging, though such applications remain largely theoretical due to the prohibitive cost and difficulty of containment.

Antimatter’s price reflects not only its rarity, but the frontier of human knowledge. Each atom represents mastery over some of the most fundamental forces of nature, making antimatter a symbol of both technological ambition and scientific humility.

2. Californium-252

Californium-252 is one of the most expensive materials that can be held in the hand, though only in vanishingly small amounts. This synthetic radioactive element does not occur naturally on Earth and must be painstakingly created in nuclear reactors.

Californium sits deep in the periodic table among the actinides, a group of heavy, unstable elements. Producing it involves bombarding lighter elements with neutrons over extended periods. Even then, only a tiny fraction of the material transforms into californium, and an even smaller fraction becomes the specific isotope californium-252.

What makes californium-252 remarkable is its intense neutron emission. A single microgram can release millions of neutrons per second. This property gives it practical value in specific, high-stakes applications. It is used to start nuclear reactors, detect hidden nuclear materials, and even in certain medical treatments where controlled neutron radiation can target cancer cells.

The expense of californium-252 arises from its scarcity, the time required to produce it, and the complexity of safely handling and storing a highly radioactive substance. Only a few facilities in the world are capable of producing it, and annual global output is measured in milligrams at most.

Each gram embodies years of reactor operation, careful chemical separation, and rigorous safety protocols. Californium-252 is expensive not because it is beautiful or durable, but because it concentrates nuclear power into an almost unimaginably small mass.

3. Diamond (High-Purity and Rare Forms)

Diamonds are often associated with luxury and romance, but their presence on this list depends on a specific category: extremely rare, high-purity, or uniquely structured diamonds. While common industrial diamonds are relatively affordable, certain natural and synthetic diamonds command extraordinary prices gram for gram.

From a scientific perspective, diamond is a crystalline form of carbon, arranged in a rigid tetrahedral lattice. This structure gives diamond its exceptional hardness, thermal conductivity, and optical properties. What elevates some diamonds into extreme value territory is not merely clarity or size, but atomic perfection and rarity.

Natural diamonds with unusual colors—such as deep blue, pink, or red—derive their hues from subtle atomic-scale defects or trace elements. These conditions are extraordinarily rare in nature. Similarly, synthetic diamonds grown with near-perfect crystal lattices are invaluable in advanced technologies, including high-power electronics, precision optics, and quantum computing research.

Producing such diamonds artificially requires extreme pressures and temperatures or advanced chemical vapor deposition techniques. The process demands precise control at the atomic level and long growth times, driving costs upward.

In these exceptional cases, diamond becomes more than a gemstone. It becomes a material platform for science and technology, valued not for ornament alone, but for properties that few other substances can match.

4. Tritium

Tritium is a radioactive isotope of hydrogen, containing one proton and two neutrons in its nucleus. It is rare, unstable, and extraordinarily valuable in specific scientific and technological contexts.

Tritium occurs naturally only in trace amounts, produced by cosmic rays interacting with Earth’s atmosphere. Most usable tritium is artificially generated in nuclear reactors by bombarding lithium with neutrons. The process is slow, tightly regulated, and technically demanding.

What makes tritium valuable is its role in nuclear fusion research and its use in specialized applications such as self-powered lighting and scientific tracers. In fusion experiments, tritium is combined with deuterium to produce helium and release energy, mimicking the processes that power stars.

The challenge with tritium lies in its radioactivity and scarcity. It decays with a half-life of just over twelve years, meaning it must be continually produced to maintain supply. Storage requires careful containment to prevent environmental release, further increasing cost.

Tritium’s price reflects the difficulty of producing and maintaining a material that sits at the boundary between current technology and humanity’s aspirations for clean, fusion-based energy.

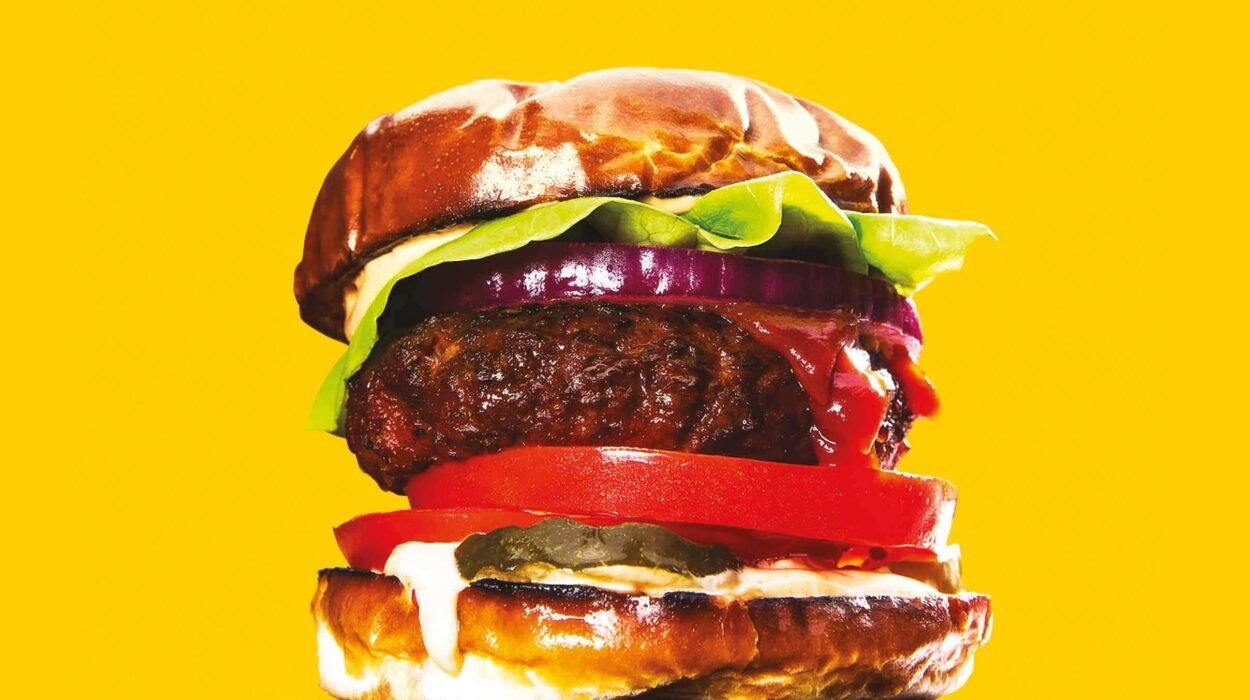

5. Taaffeite

Taaffeite is one of the rarest gemstones known to science, and its discovery is a reminder that even in the modern era, entirely new minerals can still be found. It was first identified not in the field, but accidentally, when a gem dealer noticed unusual optical properties in a stone thought to be spinel.

Chemically, taaffeite is a complex oxide containing magnesium, beryllium, and aluminum. What sets it apart is its extreme rarity. For every million diamonds mined, only a handful of taaffeite specimens may exist. Many known examples are smaller than a gram, making larger pieces extraordinarily valuable.

From a scientific standpoint, taaffeite’s rarity is linked to the precise geological conditions required for its formation. It forms only under specific combinations of temperature, pressure, and chemical environment, conditions that are seldom met and even more rarely preserved.

Taaffeite has little industrial use; its value lies almost entirely in its scarcity and beauty. Yet that scarcity itself is a scientific phenomenon, a consequence of Earth’s deep geological processes playing out over immense timescales.

6. Painite

Once recognized by Guinness World Records as the rarest mineral on Earth, painite occupies a unique place in both mineralogy and value. For decades after its discovery, only a few specimens were known, giving it an almost mythical status.

Painite is a borate mineral containing calcium, zirconium, and aluminum. Its formation requires a precise chemical balance and geological environment that occurs only in a handful of locations worldwide. Even today, despite the discovery of additional deposits, high-quality painite remains exceptionally scarce.

The scientific interest in painite lies in what it reveals about mineral formation. Its existence challenges assumptions about how elements combine in Earth’s crust and highlights the complexity of geological chemistry.

As with taaffeite, painite’s value is not tied to industrial utility but to rarity. Each gram represents an improbable convergence of geological factors, frozen into crystal form over millions of years.

7. Plutonium (Weapons-Grade Isotopes)

Plutonium is a name that carries immense historical and scientific weight. Certain isotopes of plutonium, particularly plutonium-239, are extraordinarily expensive to produce due to the complexity and danger involved in their creation.

Plutonium does not occur naturally in significant quantities. It is produced in nuclear reactors when uranium absorbs neutrons and undergoes radioactive decay. Extracting and refining plutonium requires sophisticated facilities, strict security, and meticulous handling to prevent contamination and misuse.

The value of plutonium reflects not market demand in a traditional sense, but the immense infrastructure required to create and manage it. Its applications include nuclear energy and, historically, nuclear weapons, making it one of the most tightly controlled materials on Earth.

From a scientific perspective, plutonium exemplifies the dual-use nature of advanced materials. It embodies both the promise of immense energy generation and the peril of destructive capability, a reminder that value can be inseparable from responsibility.

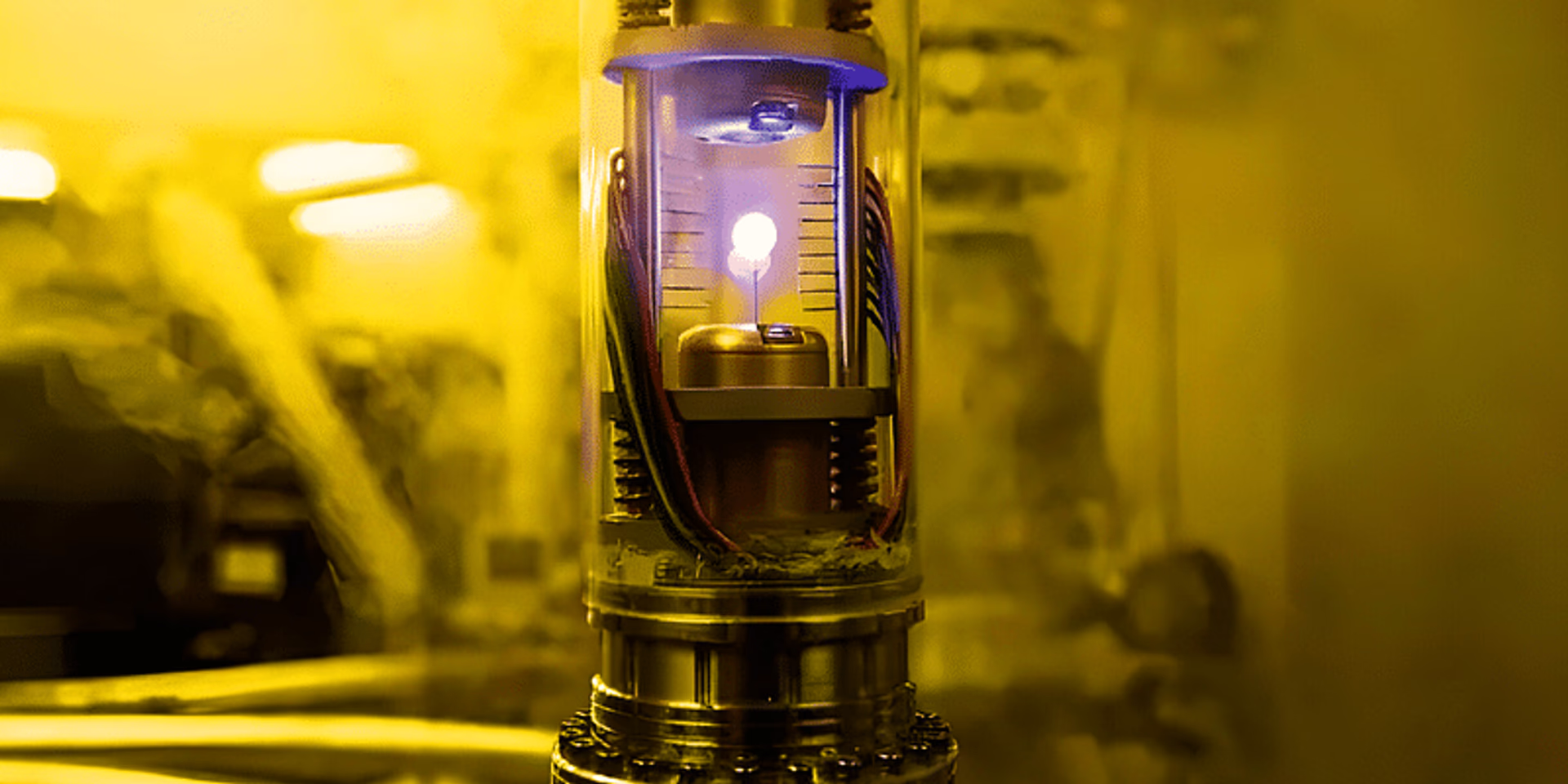

8. Endohedral Fullerenes and Advanced Quantum Materials

The final entry on this list represents not a single substance, but a class of advanced materials engineered at the atomic level. Endohedral fullerenes, for example, are carbon cage molecules that trap individual atoms inside. Producing them requires precise laboratory conditions and yields extremely small quantities.

These materials are valuable because of their potential in quantum computing, advanced electronics, and fundamental physics research. Each gram contains an astronomical number of precisely structured molecules, each representing a triumph of nanoscale engineering.

The cost arises from complexity rather than rarity in nature. These materials must be synthesized through multistep processes, often with low yields and high failure rates. Their value reflects the frontier of materials science, where atomic arrangement determines function.

Conclusion: Value Beyond Price

The most expensive materials on Earth are not merely commodities; they are milestones in humanity’s relationship with nature. Each gram encapsulates extreme rarity, profound scientific understanding, or technological mastery. From antimatter, which challenges our control over the fundamental laws of physics, to rare gemstones shaped by geological chance, these materials reveal what we value when resources are limited and knowledge is hard-won.

Ultimately, their worth lies not only in monetary terms, but in what they teach us. They remind us that value is born from effort, curiosity, and the relentless human drive to explore the limits of what is possible.