In a quiet lab at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where wires snake around EEG machines and volunteers sit beneath neural monitors, a team of neurologists and AI specialists set out to answer a timely question: What happens to our brains when we outsource thinking to artificial intelligence?

As large language models (LLMs) like ChatGPT become fixtures in classrooms, offices, and everyday life, the ease they offer is undeniable. Need an email written? A summary of an article? An essay on a complicated topic? LLMs promise answers in seconds. But beneath the surface of convenience, MIT researchers have discovered something more unsettling: frequent use of AI for writing may be weakening our brains’ capacity for deep thinking.

Their study, recently published as a preprint on the arXiv server, found that people who relied on ChatGPT to help write essays showed significantly lower brain activity than those who worked without any tools. Over time, that pattern became more pronounced—and potentially harder to reverse.

Wiring the Mind to Measure Thought

To uncover the effects of AI-assisted writing, the research team recruited 54 volunteers and divided them into three groups. One group wrote essays entirely on their own—no tools, no help. The second group was allowed to use Google Search for research. The third group used ChatGPT to guide their writing.

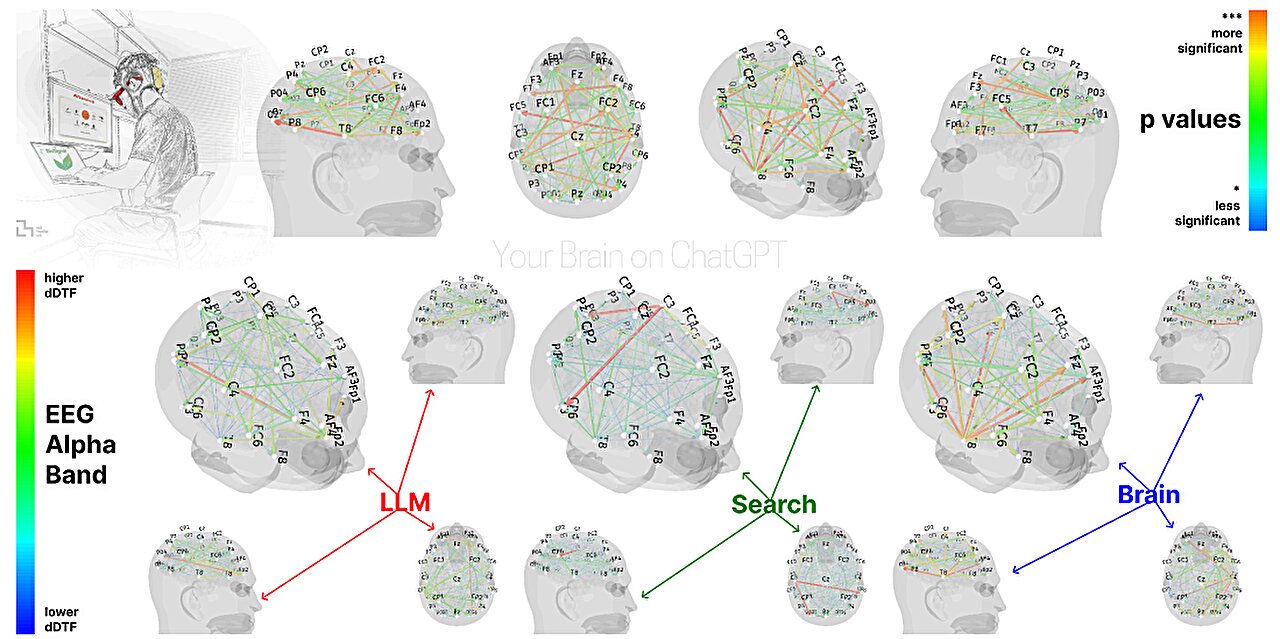

Each volunteer was tasked with writing a 20-minute essay on the topic of philanthropy across three sessions. But this wasn’t just a writing exercise. While composing their essays, participants wore EEG (electroencephalogram) caps that recorded electrical activity in their brains. These signals provided a window into cognitive processes like mental effort, memory access, and network connectivity.

What the researchers saw in the brain data was striking.

The group writing without assistance—the “Brain-only” group—showed the strongest and most widespread neural activity. Their brains lit up in networks associated with attention, memory, and internal reasoning. The Google group showed intermediate activity, as they still had to read, synthesize, and write. But the ChatGPT group? Their neural signatures were quieter, with less activity across key cognitive regions.

Essays Without Echoes

Beyond the brain scans, the researchers dove into the content and the experience of writing itself. They used natural language processing tools to analyze the structure and originality of the essays, then brought in human evaluators—and an AI agent—for scoring. They also conducted interviews with participants after each session.

The results painted a consistent picture: the Brain-only group produced more nuanced essays, scored higher on creativity and coherence, and—perhaps most importantly—felt more connected to their own ideas.

In contrast, those using ChatGPT often struggled to recall details from their own writing just moments after finishing. They expressed less ownership over their work and admitted to feeling somewhat detached from what they’d written. The AI had helped them build something, yes—but it wasn’t entirely theirs.

“This wasn’t just a drop in performance,” said Dr. Mira Solana, one of the study’s lead neuroscientists at MIT’s Media Lab. “We were seeing a cognitive shift—less engagement, less memory encoding, and a weaker relationship between the writer and the work.”

When the Tools Become the Teacher

To test how enduring these effects might be, the researchers brought back 18 of the original participants several months later for a follow-up session. This time, they switched roles: the original ChatGPT users now had to write essays without any tools, and the Brain-only participants were allowed to use ChatGPT.

What happened next was even more revealing.

Those who had previously written unaided retained strong neural engagement—even when using ChatGPT. But those who had relied on AI during the first three sessions now struggled. Their brain activity during solo writing was lower than expected, and they recalled fewer details. In short, previous reliance on AI seemed to impair their ability to think and write critically, even when the AI was no longer in use.

“It’s as if the cognitive muscles had atrophied,” said Dr. Solana. “Like any skill, critical thinking requires regular use. If AI is doing the heavy lifting, the brain doesn’t get the workout it needs.”

The Lure of Effortless Creation

The findings raise a profound dilemma: LLMs like ChatGPT are undeniably powerful, helping users write faster and with greater ease. For students, professionals, and even casual users, these tools can be lifelines in moments of deadline pressure or creative fatigue.

But the trade-off, this study suggests, may be long-term erosion of the very skills we prize most—original thought, memory formation, and the ability to reason through complex ideas.

And it’s not just about what the brain doesn’t do. It’s also about what the user feels. When asked about their sense of authorship, ChatGPT users consistently reported that their essays felt like products, not expressions. “It was like I was editing something written by someone else,” one participant said. “Even though I typed it, I didn’t feel like I owned it.”

Rethinking the Role of AI in Learning

The implications ripple far beyond academia. As more companies adopt LLMs for reports, pitches, and correspondence, and as educational institutions grapple with whether to embrace or restrict their use, the MIT study injects a note of caution into the enthusiasm.

“We’re not anti-AI,” said Dr. Kunal Rao, an AI ethicist on the study team. “But we are deeply concerned with how we use it, especially in environments where learning and critical thinking should be the goal.”

The research team emphasizes that occasional AI use is unlikely to do harm. The concern lies in habitual, passive reliance—where the machine becomes the default and the human becomes an editor, not a creator.

It’s not a question of banning the tools, but of understanding their effects. Just as calculators didn’t erase math education but reshaped it, LLMs may need to be integrated in ways that preserve, not replace, human thought.

Back to the Blank Page

For now, the message is clear: writing still matters—not just as a means of communication, but as a form of cognitive training. The blank page is more than intimidating—it’s transformative. It asks us to retrieve, connect, imagine, and revise. It activates the brain in ways no shortcut can.

As AI grows more seamless, the temptation to lean on it will only increase. But if we want to think deeply, learn meaningfully, and retain ownership of our ideas, we may need to put our brains—fully—back into the process.

Because what makes writing powerful isn’t just the words on the page. It’s the mental journey to get there.

Reference: Nataliya Kosmyna et al, Your Brain on ChatGPT: Accumulation of Cognitive Debt when Using an AI Assistant for Essay Writing Task, arXiv (2025). DOI: 10.48550/arxiv.2506.08872