For as long as human beings have lived in what is now California, the Sierra Nevada’s granite peaks have held on to their crowns of ice. These glaciers, gleaming like frozen jewels beneath the sun, have shaped not only the mountains themselves but also the lives and stories of the people who have walked their valleys and forests. New research now reveals something even more remarkable: these glaciers have likely endured since the end of the last Ice Age more than 11,000 years ago, a time when mammoths still roamed and human footprints were just beginning to mark the Americas.

But endurance does not mean immortality. These once-majestic rivers of ice, already greatly diminished, are retreating year by year. Scientists now warn that within this century the Sierra Nevada may be glacier-free for the first time in human history. The peaks of Yosemite, long draped with ice, may soon stand bare, stripped of a legacy older than civilization itself.

Tracing the Past Through Stone

To peer into the past of these glaciers, researchers turned not only to ice but to the bedrock beneath it. By chipping away at rocks near the glacier margins and analyzing the chemical signatures within, scientists can determine how long those stones have been shielded from the open sky. Their results were startling. At two of the Sierra’s largest glaciers, including one in Yosemite National Park, the rocks suggest continuous coverage by ice since the end of the last Ice Age. Another smaller glacier, nearly gone today, has existed for at least 7,000 years—far longer than anyone had previously imagined.

These discoveries, published in Science Advances, push back the timeline of California’s glacial history. They reveal that the Sierra Nevada’s icy peaks have been a constant presence for every generation of people to ever gaze upon them. For millennia, these glaciers endured droughts, heat waves, and storms. And yet, now, in the space of a single human lifetime, they are vanishing.

A First in Human Memory

“Once these glaciers die off, we will be the first humans to see ice-free peaks in Yosemite,” said Andrew Jones, lead researcher from the University of Wisconsin–Madison. His words carry both the weight of science and the gravity of grief. The glaciers’ disappearance would not only alter the Sierra Nevada’s landscapes but also mark a profound rupture in human history.

When people first arrived in the Americas some 20,000 years ago, glaciers had already carved the Sierra’s valleys and nourished its rivers. They were a backdrop to stories, a constant in the environment, a part of the rhythm of life. A glacier-free Sierra Nevada would be unprecedented. It would represent a change not only of climate but of identity—a crossing into territory no previous generation of humans has known.

The Shrinking Giants

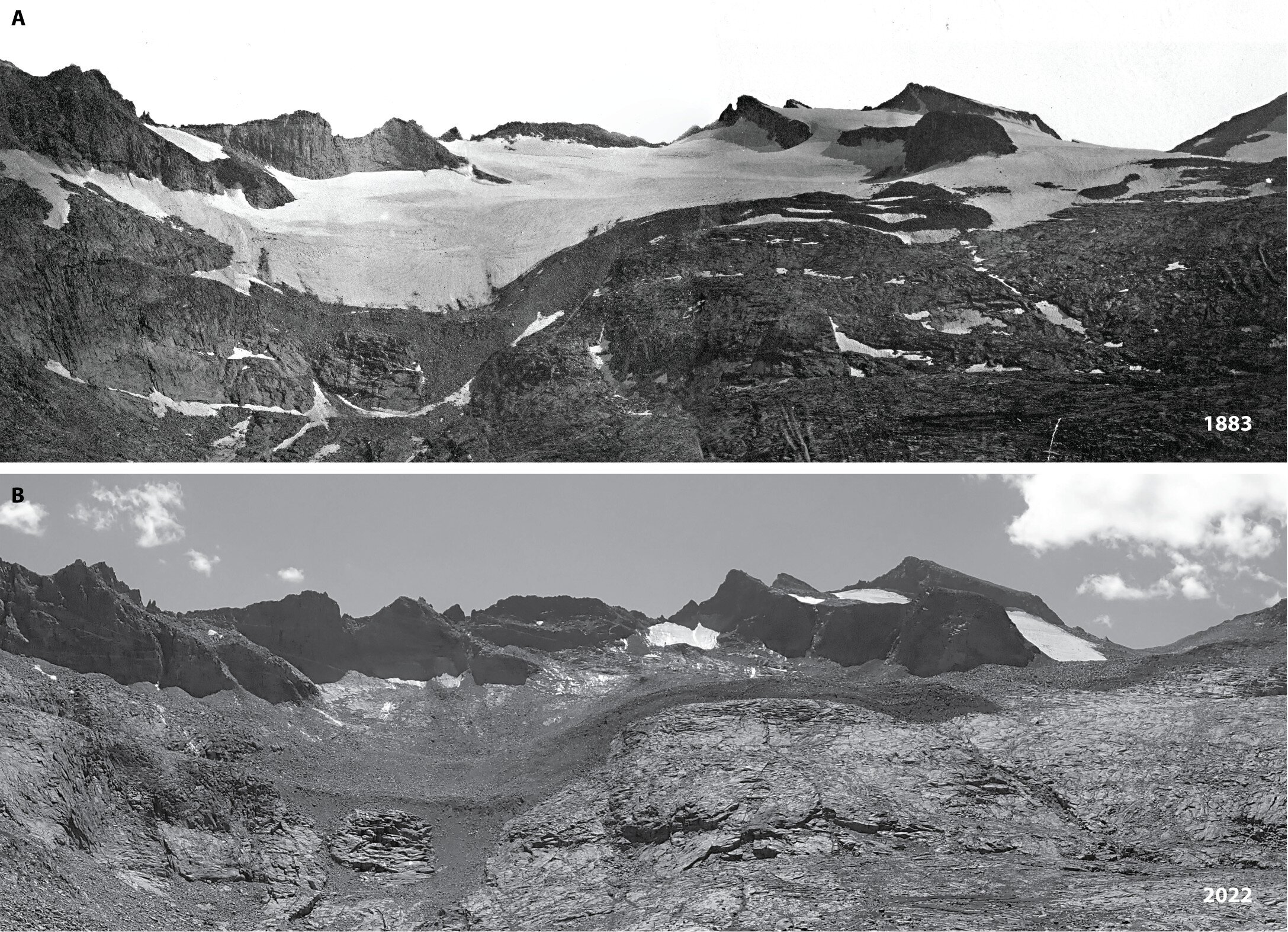

The retreat of these glaciers is not subtle. Since the late 1800s, scientists estimate that many Sierra Nevada glaciers have lost between 70% and 90% of their ice. Photographs, maps, and written accounts bear witness to the speed of the loss.

In 1872, naturalist John Muir drove wooden stakes into the Maclure Glacier to track its movement, writing of his thrill at watching rocks and soil pushed by a living river of ice. Eleven years later, geologist Israel Russell photographed the Lyell Glacier as a single mighty ice sheet. Today, that glacier is fragmented into two shrinking remnants, the east and west portions, with the east having lost about 95% of its volume since Muir’s time. Where Muir once shouted “A living glacier!” hikers now see exposed stone and thin, fragile remnants of ice.

The transformation is as much emotional as it is physical. To witness these glaciers wither is to watch the slow erasure of something ancient, something that seemed untouchable. It is as if the mountains themselves are growing old before our eyes.

Glaciers as Lifelines

The importance of these glaciers is not merely aesthetic or symbolic. They play a crucial role in sustaining the Sierra Nevada’s ecosystems and California’s water supply. Each winter, snow blankets the mountain slopes, then melts in spring to feed streams and rivers. But by late summer, when snowpacks are gone, it is the glaciers—lingering in shaded valleys—that release meltwater. This water serves as a stabilizing force, keeping rivers flowing during the driest months and sustaining life in alpine meadows, forests, and beyond.

Glacial melt feeds streams like those that flow into the Tuolumne River, one of Yosemite’s lifelines. Without this trickle of ice-fed water, those streams risk running dry during hot summers or prolonged droughts. The Sierra’s glaciers act like savings accounts, storing frozen reserves that release when needed most. As they vanish, that safety net frays.

Climate Change Written in Ice

The disappearance of glaciers in the Sierra Nevada is not an isolated tragedy. Across the planet—from the Himalayas to the Andes, from the Alps to Alaska—glaciers are retreating. They are some of the clearest and most visceral indicators of a warming climate.

In California, average summer temperatures have risen about 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit in the past century. Glaciers, exquisitely sensitive to such shifts, are responding with relentless retreat. Snowlines are creeping higher each year, reducing the area where glaciers can even form. Scientists describe glaciers as “sensitive climate indicators,” and in their retreat, they are sounding an alarm.

Andrew Jones and his colleagues, who visited the Sierra glaciers in 2018, 2021, and 2023, describe the experience as deeply visceral. To see the exposed rock where ice once lay, to hold evidence of thousands of years of continuity now dissolving—it is to stand at the intersection of past and future. “Glaciers are touchstones between the past and the present,” Jones said. “It’s just so visceral when you can see how it used to be and how it is today.”

What We Stand to Lose

The loss of glaciers is not only a scientific concern. It is a cultural and emotional rupture. For generations, writers, artists, and travelers have been awed by the Sierra’s ice. John Muir, the “father of the national parks,” built his philosophy of wild preservation in part upon his encounters with these glaciers. He saw them as living, breathing beings—slow but purposeful, shaping valleys and sculpting cliffs.

To lose them is to lose a part of that legacy. The Sierra Nevada without its glaciers is not the same Sierra Nevada that Muir walked. It is a different place, a diminished place. Future generations may know Yosemite only as granite and forest, never realizing that for millennia, it was also a kingdom of ice.

A Call to Action

And yet, the story is not entirely one of despair. The fate of glaciers, though deeply tied to climate, is not sealed beyond influence. Jones and his fellow scientists point out that while many small glaciers are already beyond saving, larger glaciers around the world still hold vast reservoirs of ice. If humanity can slow the pace of warming—if greenhouse gas emissions are curbed through global action—then many glaciers can still be preserved.

“If we can keep warming to a modest level instead of a really high level, you actually preserve a large number of glaciers that would be lost,” Jones explained. It is a call for urgency, but also for hope. The future of ice is not only written in physics and chemistry; it is written in politics, choices, and collective will.

The Line in the Sand

What is happening in the Sierra Nevada is more than a local story. It is a glimpse of what is unfolding across the planet. As glaciers retreat, they reveal not only bare stone but the consequences of a changing climate. They tell us, in the starkest terms, that we have stepped beyond the boundaries of what has been “normal” for all of human history.

We are the first generation to witness these losses, and we may be the last with the power to slow them. The Sierra’s glaciers are dying, but their story—written in ice, rock, and memory—offers us a mirror. It asks us to decide what kind of world we will leave behind.

To stand at the edge of a glacier and hear the water trickle from its melting ice is to listen to the sound of time itself slipping away. It is a sound that urges us to remember, to act, and to hope. For glaciers are not only frozen rivers of the past—they are warnings for the future.

More information: Andrew G. Jones et al, Glaciers in California’s Sierra Nevada are likely disappearing for the first time in the Holocene, Science Advances (2025). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adx9442