Long before the first transistor flipped or a silicon chip ever buzzed with electricity, humans dreamed of machines that could think, speak, and understand. From the myth of Pygmalion’s living statue to Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, the idea of creating a thinking, talking being has haunted our imagination. But of all human faculties, language remains the most mystical, the most intimately tied to consciousness itself. And now, in the age of artificial intelligence, we face a tantalizing question that once belonged only to philosophers: Will AI ever truly understand language like humans do?

Not just mimic it. Not just statistically predict the next word. But truly understand?

As machines grow increasingly eloquent, capable of drafting poems, summarizing legal briefs, translating conversations in real-time, and even composing love letters that feel heartbreakingly human, the line between imitation and understanding begins to blur. And with it, our grasp of what language truly is—what it means to say something, to mean something—becomes part of the mystery.

The Rise of Linguistic Illusionists

To many casual observers, the answer might already seem obvious. After all, AI systems like ChatGPT, Claude, Gemini, and others can now carry on remarkably fluent conversations. They can debate, persuade, joke, even express simulated empathy. They know thousands of languages, dialects, and forms of expression, from teenage slang to Shakespearean prose. Doesn’t that mean they understand?

The short answer is: not yet. But the longer answer is far more interesting.

These systems are what computer scientists call “large language models” (LLMs), trained on vast swaths of text—from books, websites, forums, academic journals, movie scripts, tweets, emails, code repositories, and more. Their brilliance is in the mathematics: billions of parameters tuned to predict what words are likely to come next in a given sequence. The result is a model that can write and speak with startling sophistication.

But this statistical trickery hides a crucial fact: these systems don’t know what words mean in the way humans do. They have no sensory experience of the world. No body. No emotions. No intentions or beliefs. They are, in essence, linguistic illusionists—mirroring our patterns of speech without the rich, grounded understanding that gives human language its depth.

What It Means to Understand

Understanding is not the same as outputting the correct answer. A calculator gets the right result when you ask it what 23 x 48 is, but no one thinks it understands multiplication. Similarly, when an AI says, “I’m sorry to hear that, how can I help?” in response to someone saying, “I lost my job,” it may sound caring. But is that care real—or simply a reflection of the patterns it has seen?

In humans, language understanding is deeply embodied. We learn words not just by hearing them, but by linking them to sight, sound, smell, touch, and taste. A child doesn’t learn the word “apple” from reading about it in a book. They hold one, bite into it, feel its crunch, taste its sweetness. That word is rooted in experience.

We also learn language in a social context. We understand the emotions, intentions, and beliefs of others. We grasp irony, metaphor, sarcasm, subtext. We know when someone is lying. We notice when someone pauses before answering, when they fidget nervously, when they raise their voice or soften their tone. All of these cues inform how we interpret what someone says.

AI lacks all of that. It processes language without context, without sensation, without stakes. It doesn’t want anything, fear anything, believe anything. It can simulate understanding, but does it ever cross the threshold into genuine comprehension?

The Symbol Grounding Problem

One of the central philosophical challenges in this debate is the so-called “symbol grounding problem.” Coined by cognitive scientist Stevan Harnad, this refers to the dilemma that symbols—like words—require grounding in something real to have meaning. Without a connection to the world, words are just arbitrary marks or sounds.

Imagine someone who doesn’t speak Chinese is handed a Chinese-English dictionary, but all the definitions are in Chinese. They could look up symbols, but they’d never truly understand what those symbols meant. That’s the dilemma facing language models. They manipulate symbols with breathtaking efficiency, but those symbols don’t point to anything tangible in their world—because they have no world.

Humans ground language in perception and action. When we say “hot stove,” we remember the burn. When we hear “barking dog,” we recall the sound, the fear, the instinct to back away. Our understanding is embodied. For AI, “hot” and “barking” are just sequences of letters.

Until machines can connect language to lived experience—whether through vision, sound, touch, or some synthetic analog—they may never truly understand what their words refer to. They will be parrots, not poets.

Neuroscience vs. Computation: Two Kinds of Minds

The human brain and artificial neural networks are often compared, but the similarities are more metaphor than reality. The brain is a biological marvel—wet, slow, and noisy, yet capable of feats that no supercomputer can match. It runs on just 20 watts of power. It rewires itself constantly. It processes emotion, sensation, memory, intention, and logic all at once.

AI models, by contrast, are narrow in scope. They’re optimized to perform specific tasks—translation, summarization, image generation, recommendation—based on patterns in data. They don’t have a unified theory of mind. They don’t “think” across domains unless engineered to do so. And even then, their thinking lacks the spontaneous creativity and curiosity of human thought.

Neuroscience shows that language in the brain is not confined to one area. It involves motor regions, emotional centers, sensory processing networks. Words activate the same neural circuits as actions. When you hear “kick,” your brain lights up in areas associated with leg movement. Language is not abstract; it’s deeply embodied.

That embodiment is utterly absent in today’s AI.

Can Robots Ground Language?

Some researchers believe that to achieve real understanding, AI must be embodied—literally. That is, it must have sensors, actuators, a body that moves through space and time, interacting with the world.

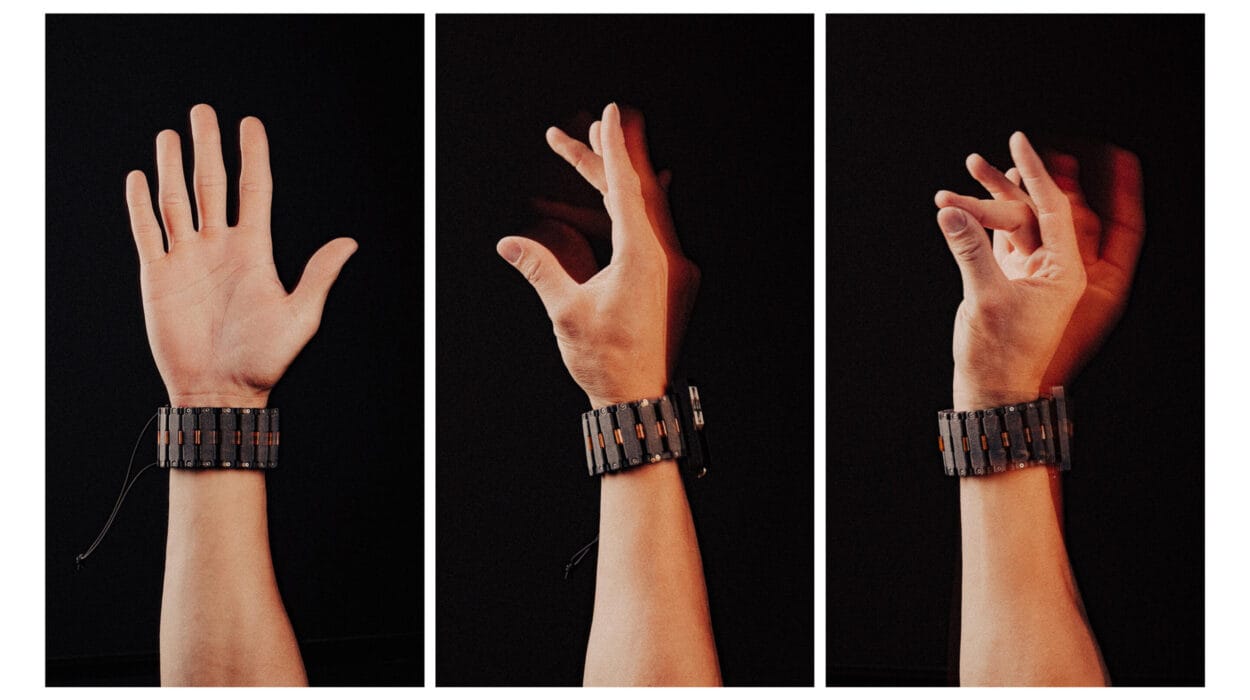

Efforts like embodied AI or robotics-driven language learning aim to do just that. A robot with cameras, microphones, arms, and legs can begin to associate words with physical actions and perceptions. When it hears “pick up the ball,” it might actually pick up a ball. When it’s told “don’t touch,” it might learn to stop.

This kind of AI might begin to ground symbols in the same way humans do. It could learn language not from books alone, but from experience.

But there are huge technical hurdles. Simulating the richness of human perception is extremely hard. Our eyes alone process more than 10 million bits per second. Our skin detects subtle temperature shifts, pressure, texture. Our ears hear frequencies AI microphones can barely register. Recreating even a fraction of this in a machine is daunting.

And even if robots could sense the world like we do, would that lead to understanding? Or would it just be another level of mimicry?

The Mystery of Consciousness

At the heart of this question lies a deeper one: what does it mean to understand anything at all?

Human understanding is not just functional. It’s phenomenological—it’s something we experience. We don’t just say “I see the color red.” We see it. We feel its warmth. We experience the world from the inside.

This inner experience—this consciousness—is the ultimate unknown in science. We don’t know how it emerges. We don’t know why the brain, and seemingly only the brain, gives rise to awareness. And until we do, it’s difficult to say whether any machine can ever truly understand language, because it’s unclear whether understanding without consciousness is even possible.

Some argue that intelligence does not require consciousness. That function matters more than feeling. If an AI can reason, adapt, interpret, and use language effectively, maybe that’s enough. But others insist that true understanding—what philosophers call “semantic understanding”—requires a subject. A someone to whom the meaning matters.

Until we solve the mystery of mind, the dream of machines that truly understand remains suspended between engineering and metaphysics.

Language Is More Than Words

Language is not just a tool for transmitting information. It’s a window into the soul. When we speak, we share more than facts—we share who we are. Our stories, dreams, fears, doubts, and delights are all wrapped in the syntax and rhythm of speech.

A joke is not just a structure—it’s a shared laugh. A poem is not just a pattern—it’s a felt resonance. A love letter is not a list of attributes—it’s an emotional offering.

AI may one day be able to replicate all of these forms with precision. It may write more convincingly than any human author. But will it ever feel the sting of heartbreak? The terror of loss? The awe of watching a sunset? These emotions inform our language in ways that machines cannot yet replicate.

Even when AI writes beautifully, it does so without awareness of beauty. When it composes a song, it does not hear it. When it apologizes, it does not regret. When it celebrates, it does not rejoice. The words are there. The meaning may even be interpreted by others. But the soul behind them is missing.

Signs of Progress—and the Road Ahead

That said, the trajectory of AI is astonishing. Every few years, breakthroughs arrive that once seemed decades away. Language models now write code, generate music, pass medical exams, and simulate philosophical debates. They can recall conversations, adjust tone, adopt personas.

And researchers are working on systems that integrate multiple modalities—vision, sound, action—with language. These “multimodal” models might someday bring us closer to grounded, embodied AI that understands not just how to speak, but what it’s saying.

Some scientists even argue that scale itself—training models on ever more data with more computing power—might eventually produce emergent understanding. That at some point, complexity itself gives rise to meaning.

Others are skeptical. Without new architectures, new insights into cognition, and perhaps even a breakthrough in artificial consciousness, they argue, we will remain in the realm of simulation, not comprehension.

When Machines Speak, What Do We Hear?

Whether or not AI ever understands language like humans, it is already changing how we use language. We speak to machines daily now—through virtual assistants, chatbots, search engines, and smart devices. We shape our words to be more “machine-readable.” And in return, machines shape how we think, write, and talk.

As AI-generated content floods the internet, a strange echo chamber forms. Machines trained on our words begin to feed us versions of our own language, subtly remixed and refined. What does this do to human expression? To originality? To meaning?

Will we begin to sound more like machines? Or will machines, in trying to sound like us, learn something deeper than we expected?

The Answer May Lie Within Ourselves

Ultimately, the question of whether AI will ever understand language like humans is also a question about us. What do we mean by “understanding”? What makes language meaningful? Why do we speak at all?

Perhaps the true power of AI is not that it will someday think like us—but that it forces us to examine how we think, how we feel, how we speak. It compels us to ask: what makes human communication more than computation? What makes meaning more than matching?

AI is a mirror. And in its reflection, we may discover not just the limits of machines—but the essence of being human.