It happens without warning. You hear a sudden sound in a quiet room, feel a cold breeze on your neck, or watch a particularly moving scene in a film. Instantly, tiny bumps rise on your skin, hairs stand on end, and a shiver courses through your body. Humans call it goosebumps, but the phenomenon is far more than a trivial quirk—it is a window into our evolutionary past, a living reminder of the survival mechanisms that once kept our ancestors alive.

Goosebumps, known scientifically as piloerection, occur when the tiny muscles at the base of hair follicles, called arrector pili, contract. This reaction causes the hair to stand upright and the skin to form small bumps. While in humans, with our relatively hairless bodies, this reaction may appear largely vestigial, in our distant mammalian ancestors, it played a crucial role in survival. To understand why goosebumps persist, we must first travel back millions of years, into a world where these small hairs were life-saving tools against predators, cold, and the unpredictable hazards of the wild.

Ancestral Armor Against the Cold

One of the most straightforward explanations for goosebumps lies in temperature regulation. In many furry animals, when the skin’s tiny muscles contract, the hairs stand erect, trapping a layer of air close to the body. This layer acts as insulation, conserving heat and keeping the animal warm in frigid conditions. For our ancestors, who lacked modern clothing, this physiological response would have been essential for surviving harsh climates.

Imagine a cold evening on the African savanna or the forests of early Eurasia. Our human predecessors, lacking thick fur like bears or wolves, would have relied on every possible mechanism to preserve warmth. The piloerection response, triggered by a sudden drop in temperature, would cause the sparse hairs to rise, increasing the layer of trapped air and providing a marginal but crucial thermal buffer. Although today the effect is largely symbolic due to our thin hair and clothing, the evolutionary imprint remains deeply embedded in our nervous system. Goosebumps are, in essence, a historical artifact—an echo of a time when our survival depended on it.

The Alarm System of Fear

Temperature alone, however, cannot explain the goosebumps that surge when fear strikes. Picture yourself alone in a dark alley, hearing footsteps behind you. The hairs on your arms stand on end, your skin tightens, and an involuntary shiver travels down your spine. This is not cold—it is a response to threat, a vestigial alarm system wired deep into your nervous system.

In mammals, this reaction served a critical purpose. When an animal senses danger, its sympathetic nervous system triggers the fight-or-flight response. Piloerection makes the creature appear larger and more threatening to potential predators. For a cat arching its back or a porcupine raising its quills, this reaction is a literal defensive posture. For early humans, raising body hair may have been a subtle, but psychologically significant, way to signal readiness to face or flee a threat. Even if the physical effect was modest due to sparse hair, the associated physiological arousal prepared the body for rapid action: heart rate increases, breathing quickens, and muscles tense, priming the organism for survival.

Emotional Resonance and the Brain

Interestingly, goosebumps are not merely about cold or fear—they are deeply connected to emotion. Music, poetry, and art can trigger the same reaction, even in the absence of any immediate threat or temperature change. This phenomenon, sometimes referred to as frisson, illustrates how evolution repurposes older mechanisms for new contexts.

Neurologically, the trigger for emotional goosebumps involves a complex interplay between the limbic system, which governs emotion, and the autonomic nervous system, which controls involuntary bodily functions. When humans experience awe, nostalgia, or profound beauty, the brain interprets these emotions as significant, prompting the release of neurotransmitters such as dopamine and norepinephrine. This cascade activates the arrector pili muscles, causing hair to rise and skin to ripple. Evolution may not have designed goosebumps for listening to a symphony, yet our ancient alarm system has found a modern stage in our emotional life.

Vestiges Across the Animal Kingdom

To fully grasp the evolutionary purpose of goosebumps, it helps to examine other animals. In cats, dogs, and primates, piloerection is an active defense mechanism. When a cat feels threatened, its fur stands on end, making it appear larger and more intimidating. Similarly, gorillas and chimpanzees raise their fur to communicate aggression or dominance. In these species, the effect is both visual and psychological—a signal to others that the animal is ready to fight.

Even in birds, a comparable mechanism exists. Feathers may puff up in response to cold or alarm, creating the same insulating and threatening effects seen in mammals. Across the animal kingdom, the principle is consistent: when faced with cold or danger, standing hairs or feathers can serve as both protection and communication. Humans retain the skeletal framework of this ancient system, even though our sparse hair diminishes its practical effect.

A Connection to Survival Instincts

From an evolutionary perspective, goosebumps illustrate how traits can persist long after their original function has faded. Our modern lives rarely require hair to stand on end for warmth or intimidation, yet the reflex remains deeply embedded. It is a testament to the durability of survival instincts, hardwired into our bodies through millions of years of natural selection.

Some researchers suggest that even in modern humans, goosebumps may retain subtle benefits. The physiological arousal associated with piloerection—heart rate acceleration, increased alertness, muscle tension—could provide a fleeting edge in moments of stress or danger, enhancing awareness and readiness. In this sense, goosebumps are not entirely obsolete; they are an evolutionary echo that continues to serve the body in nuanced ways.

Cultural Interpretations and Symbolism

Beyond biology, goosebumps have seeped into human culture, often carrying symbolic meaning. Across societies, they are linked with awe, reverence, and the sublime. A soldier hearing a national anthem, a child witnessing a fireworks display, or a listener captivated by a haunting melody may all experience the same tiny bumps on the skin. Cultures interpret this involuntary reaction as evidence of the soul being moved, of emotions transcending the ordinary.

Literature and art have long captured the sensation. Poets describe it as a thrill, a shiver of the spirit, an acknowledgment of forces greater than oneself. Psychologists, meanwhile, recognize it as a measurable physiological response, connecting subjective experience to ancient mechanisms honed by evolution. Goosebumps bridge the physical and the emotional, the biological and the aesthetic, revealing how the body and mind co-evolve to interpret and react to the world.

The Science Behind the Shiver

From a molecular perspective, the goosebump response begins with the release of noradrenaline from nerve endings in the skin. This neurotransmitter stimulates the arrector pili muscles, causing them to contract. In parallel, other systems are activated: the cardiovascular system pumps blood more vigorously, the respiratory system quickens, and the brain heightens awareness. Even the hair follicles themselves contain sensory receptors, further amplifying the sensation.

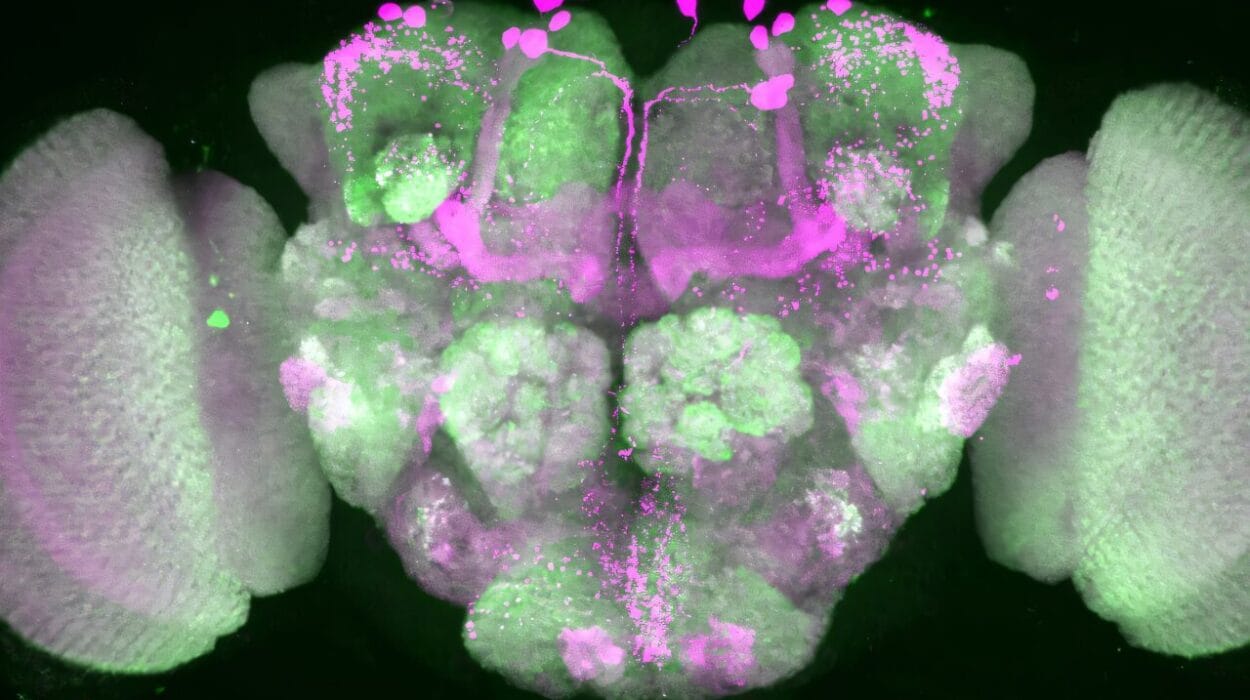

Studies using neuroimaging have shown that the experience of emotional goosebumps engages the insula, a region of the brain associated with body awareness and emotion, as well as the amygdala, which processes fear and threat. This convergence of ancient and modern neural circuits illustrates how a survival mechanism has been woven into the fabric of human experience, shaping both perception and feeling.

When Goosebumps Signal More

Though usually benign, goosebumps can sometimes signal underlying conditions. Persistent or excessive piloerection, accompanied by other symptoms, can indicate hormonal imbalances, neurological disorders, or stress-related syndromes. Yet in everyday life, they remain a harmless, fascinating insight into our biology—an intimate reminder of our evolutionary heritage.

Modern Life and Ancient Reflexes

In contemporary society, goosebumps often appear in situations far removed from their original purpose. Watching a suspenseful film, listening to an emotional song, or recalling a vivid memory can elicit the same reaction that once served as a literal alarm. In this way, humans have repurposed an evolutionary tool, transforming a survival reflex into a conduit for aesthetic and emotional experience.

The persistence of goosebumps highlights a fundamental principle of evolution: traits are rarely perfect; they are adaptive solutions honed for past challenges, retained even when circumstances change. Our bodies carry echoes of earlier worlds, and each shiver is a reminder of the invisible threads linking us to the mammals and ancestors who came before.

A Shiver Into the Past

Goosebumps, trivial as they may seem, are a profound reminder of human continuity with the natural world. They connect us to cold nights, lurking predators, and the relentless drive to survive. They are both alarm and thrill, fear and wonder, a biological legacy written in our very skin.

Next time your hairs rise in the theater of life, consider the journey of this simple reflex—from shivering ancestors to emotional resonance, from survival mechanism to aesthetic thrill. In that tiny contraction of muscle, in the prickle along your arms, lies a story millions of years in the making. Goosebumps are evolution’s leftover alarm system, a whisper of history and a pulse of life, reminding us that beneath our polished modernity, the ancient instincts still run, still respond, still matter.