In 2006, a decision was made by the International Astronomical Union (IAU) that sent shockwaves through science classrooms, planetariums, textbooks, and the hearts of stargazers across the globe. Pluto—the icy, distant world discovered in 1930, the ninth and once-final planet of our solar system—was reclassified. Overnight, it was no longer a planet.

This decision sparked controversy, confusion, and even grief. People felt they had lost a friend, a familiar dot at the edge of the solar system. T-shirts and bumper stickers proclaimed “Pluto is still a planet in my heart.” Some scientists hailed the change as a necessary step for clarity and scientific consistency, while others saw it as arbitrary, even political.

But what really happened? Why was Pluto demoted? The story is more than just a vote at a conference—it’s a tale of discovery, evolving definitions, new technology, and a rapidly expanding understanding of our cosmic neighborhood.

To understand why Pluto lost its planetary status, we must first understand what Pluto is, how it was discovered, and how our concept of what makes a planet has changed over time.

The Discovery of Pluto: A Planet Is Born

In 1930, a young American astronomer named Clyde Tombaugh made history. Working at the Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona, Tombaugh was on a mission to find a ninth planet, sometimes called “Planet X,” which astronomers believed might be influencing the orbits of Uranus and Neptune.

Tombaugh painstakingly compared photographic plates of the night sky, taken days apart, using a blink comparator—a device that allowed him to rapidly flip between two images to spot anything that had moved. On February 18, 1930, he noticed a tiny, shifting dot. It was a distant object far beyond Neptune, and it was eventually named Pluto.

At the time, Pluto’s discovery was a moment of triumph. It seemed to confirm theories about a mysterious planet lurking beyond Neptune. The name “Pluto,” suggested by an 11-year-old girl in England named Venetia Burney, honored the Roman god of the underworld—a fitting moniker for a cold, dark world at the edge of the known solar system.

Pluto joined the ranks of Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune as the ninth planet. Textbooks were updated. Models of the solar system were revised. And for over 75 years, Pluto held that planetary title.

But from the beginning, Pluto was different.

Pluto: The Oddball Planet

Shortly after its discovery, astronomers began to suspect that Pluto was not like the other planets. For one thing, it was tiny—far smaller than Earth, and even smaller than Earth’s moon. Initial estimates of Pluto’s size were wildly off, but by the mid-20th century, it was clear that Pluto was an unusual world.

Its orbit was another oddity. Unlike the mostly circular orbits of the other planets, Pluto’s orbit was highly elliptical, taking it inside Neptune’s orbit for 20 years during its 248-year trip around the sun. From 1979 to 1999, Pluto was actually the eighth planet from the sun, not the ninth.

Even stranger, Pluto’s orbit was tilted by about 17 degrees relative to the rest of the planets, which orbit in a relatively flat plane. This inclined orbit suggested that Pluto might be more like a large comet or a different class of solar system object.

Despite these quirks, Pluto remained a planet. But in the late 20th century, new discoveries began to challenge its status.

The Kuiper Belt and the Rise of the Icy Dwarfs

In the 1990s, astronomers began to discover a vast population of icy bodies beyond Neptune—objects that came to be known as Kuiper Belt Objects (KBOs). The Kuiper Belt, a ring of frozen remnants from the early solar system, extends far beyond Neptune and contains hundreds of thousands of icy bodies.

As more KBOs were found, many of them showed striking similarities to Pluto. Some had similar orbits, compositions, and sizes. It soon became clear that Pluto was not alone. It was, in fact, just one of many frozen objects populating this distant region.

Then came the discovery that changed everything.

Eris: Pluto’s Rival

In 2005, astronomers led by Mike Brown at the Palomar Observatory in California discovered a new object orbiting the sun far beyond Pluto. This object, initially named 2003 UB313 and later officially named Eris, appeared to be roughly the same size as Pluto—and perhaps even larger.

Eris, like Pluto, was an icy world in a highly elliptical orbit. But its discovery posed a major problem. If Pluto was a planet, then Eris, being of comparable size, must be one too. But Eris wasn’t the only contender—dozens of similar bodies were being discovered in the outer solar system. Were we to suddenly recognize dozens of new planets?

This forced astronomers and the International Astronomical Union to confront a difficult question: What exactly is a planet?

The Definition of a Planet: A Crisis in Classification

For centuries, the word “planet” had a flexible meaning. The ancients used it to describe the “wandering stars” that moved against the background of the fixed stars. Over time, the term evolved as telescopes revealed more about the cosmos. But there had never been a precise, universally accepted definition.

By 2006, the situation had become untenable. Pluto, Eris, and potentially many other Kuiper Belt Objects were challenging the traditional planetary roster. Would schoolchildren have to memorize dozens of planets? Could Pluto and Eris be lumped together? Should we classify them differently?

At the 2006 meeting of the International Astronomical Union in Prague, the world’s leading astronomers gathered to settle the matter.

After much debate, the IAU voted to adopt a new, formal definition of a planet. According to the resolution, a planet must meet three criteria:

- It must orbit the sun.

- It must be massive enough for its gravity to shape it into a roughly spherical form.

- It must have “cleared the neighborhood” around its orbit, meaning it is gravitationally dominant and has removed smaller objects near its path.

Pluto met the first two criteria—it orbits the sun, and it’s round. But it failed the third. Pluto shares its orbital zone with other Kuiper Belt Objects and is not dominant in its region. Therefore, under this new definition, Pluto was no longer classified as a planet.

Instead, it was assigned a new category: “dwarf planet.”

The Aftermath: Outrage, Acceptance, and the Cultural Fallout

The reclassification of Pluto was not met with universal approval. In fact, it sparked an emotional backlash unlike anything seen in the field of astronomy before.

Many people felt personally attached to Pluto. It had been part of schoolbooks and space posters for generations. Its demotion felt like an insult to childhood memories. T-shirts read “Pluto: Revolving in Peace” or “When I was your age, Pluto was a planet.” Some U.S. state legislatures even passed symbolic resolutions recognizing Pluto’s planetary status in protest.

Even within the scientific community, there was disagreement. Some astronomers, including Alan Stern, the principal investigator of NASA’s New Horizons mission to Pluto, argued that the IAU’s definition was flawed. Stern pointed out that the “clearing the neighborhood” criterion excluded Earth-like planets in other star systems, and possibly even Earth itself in certain orbital zones.

Stern and others advocated for a broader definition—one that would include Pluto and similar bodies as planets, even if it meant dramatically increasing the number of recognized planets.

Meanwhile, others supported the IAU’s decision, arguing that a stricter definition was necessary to maintain clarity and order as new celestial bodies continued to be discovered.

NASA’s New Horizons: Rediscovering Pluto

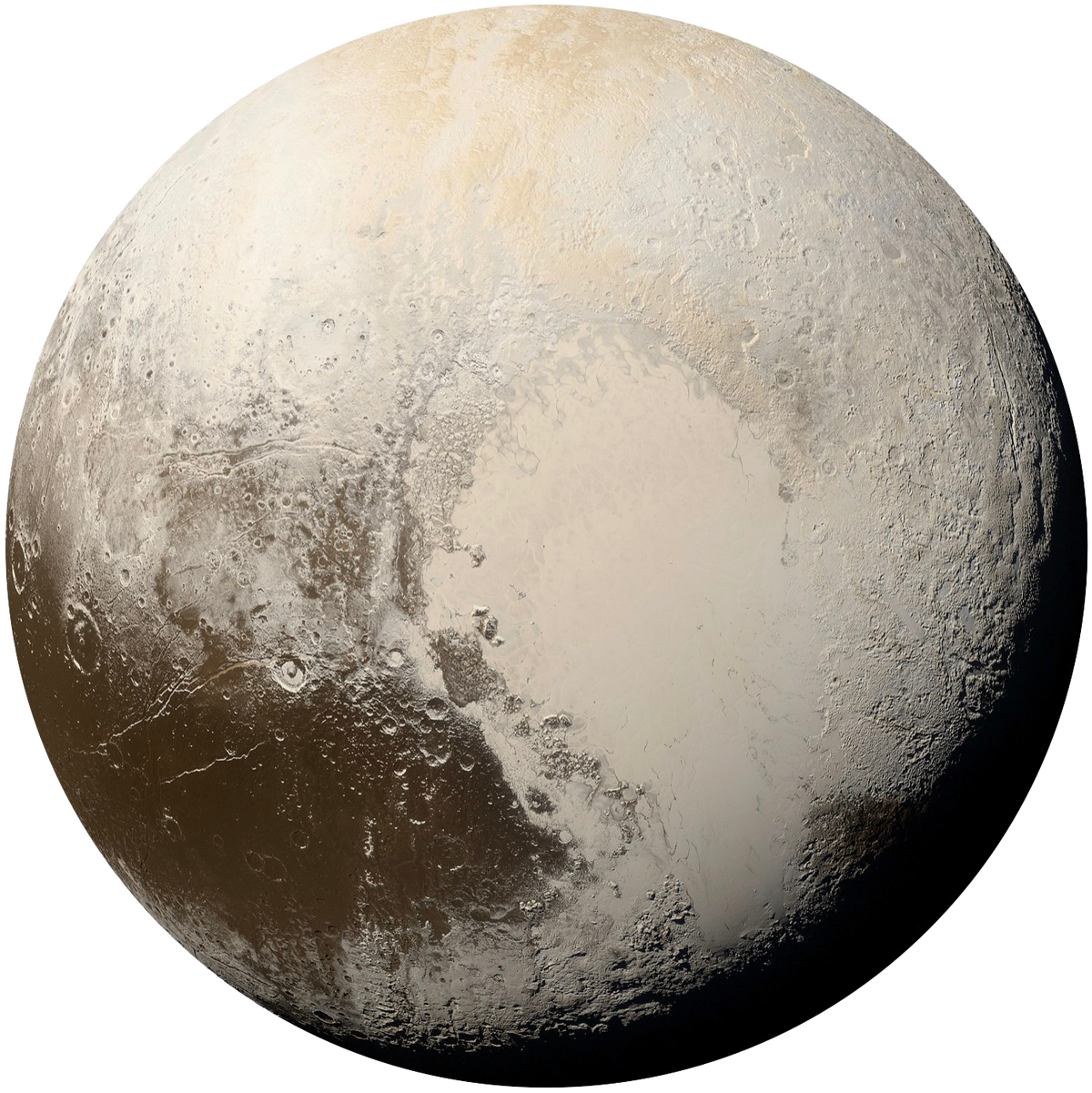

In July 2015, almost a decade after Pluto’s demotion, NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft made history by flying past Pluto, capturing the most detailed images and data of the dwarf planet ever obtained.

What New Horizons revealed was breathtaking. Far from being a static, frozen rock, Pluto was a dynamic world with ice mountains, nitrogen glaciers, a thin atmosphere, and possible signs of subsurface oceans. It had a complex geological history and was far more active than anyone had expected.

Pluto’s largest moon, Charon, was also shown to be an intriguing world in its own right. The entire Pluto system appeared more like a miniature planetary system than a collection of icy rocks.

These revelations reignited the debate. How could such a complex, fascinating world not be a planet? The images from New Horizons made many question the IAU’s decision, and the call to restore Pluto’s planetary status gained renewed energy.

Dwarf Planets and a New Era of Exploration

Today, Pluto is the most famous member of a growing group known as dwarf planets. This category includes Eris, Haumea, Makemake, and Ceres—the latter of which resides in the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter.

These dwarf planets are worlds unto themselves, each with unique features, moons, atmospheres, and mysteries. They represent a frontier in planetary science, helping astronomers understand how solar systems form and evolve.

As telescopes grow more powerful and space missions reach further, new dwarf planets are being discovered all the time. Some astronomers believe there may be a true “Planet Nine” lurking in the far reaches of the solar system—much larger than Pluto, still undetected, and capable of explaining odd orbital behavior in the Kuiper Belt.

In this sense, Pluto’s demotion was not the end of an era but the beginning of a new one—one that embraces complexity and expands our definition of what a world can be.

Conclusion: What Does It Mean to Be a Planet?

The story of Pluto is not just about classification—it’s about how science works. Definitions evolve as new data emerges. Categories shift to reflect better understanding. Science is not static; it is a living, breathing pursuit of truth.

Pluto was once the ninth planet. Today, it is a dwarf planet. But those labels don’t diminish its importance. If anything, they enhance it. Pluto now stands at the crossroads of astronomy, planetary science, and public imagination.

Whether or not we call it a planet, Pluto remains a beloved and mysterious world, challenging us to rethink our place in the cosmos. It reminds us that the universe is more complicated, more beautiful, and more surprising than we ever imagined.

Pluto’s journey—from discovery to demotion to rediscovery—mirrors our own evolving relationship with the universe. And in that story, Pluto remains, in every meaningful sense, a planet of the heart.