Every morning, you wake up, stumble to the bathroom, and glance at the mirror. The face staring back at you has been yours for as long as you can remember. And yet, that simple reflection cannot begin to capture the complexity of who you are. Because what makes you “you” isn’t just your body, your name, or the memories you carry. It’s something deeper, more elusive, something at once solid and fluid, enduring and ever-changing.

What makes you you?

It’s a question that has captivated philosophers, psychologists, neuroscientists, and poets for centuries. And while we might never capture the full essence of identity in a single theory or brain scan, science has begun to uncover the astonishing architecture behind our sense of self. It’s a story that unfolds in the folds of your brain, the whispers of your memories, the shape of your relationships, and the culture that raised you. And it all begins not with a grand answer—but with a quiet question.

The Search for the Self

Long before psychology existed as a science, thinkers like Socrates, Descartes, and Buddha pondered the self. Some saw it as an immortal soul. Others, as a bundle of ever-shifting experiences. Still others suggested the self was an illusion entirely.

Modern psychology approaches identity not as a fixed object, but as a process—a dynamic construction that emerges from the interplay of biology, memory, emotion, cognition, and environment. You are not a singular thing, but a story in motion.

Psychologist Erik Erikson described identity as a lifelong project—a narrative we build over time, shaped by crises, roles, and social feedback. From childhood to old age, we are constantly revising the answer to the question: “Who am I?”

And the fascinating truth is, your brain is built to tell that story. Even when you’re not actively thinking about it, your mind is quietly, constantly stitching together a narrative of you.

The Brain’s Narrative Machine

Inside your skull is the most sophisticated identity engine ever created: the human brain. Among its many tasks—processing language, regulating emotion, guiding movement—perhaps none is more extraordinary than its ability to create a self.

Neuroscientists have pinpointed several key brain regions involved in self-related processing. The medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) is active when you think about your traits, desires, or emotions. The posterior cingulate cortex lights up when you reflect on your past. The temporoparietal junction helps you understand others’ minds—and distinguish them from your own.

But identity isn’t just stored in a single place. It’s woven through networks—emotional, sensory, linguistic. Your memories don’t sit in one corner of your brain like files in a cabinet. They’re distributed across multiple regions, activated in patterns that reflect not just facts, but feelings, contexts, and meanings.

This is why your identity isn’t just what you remember, but how you remember. A childhood memory of failure, framed with shame, becomes part of a different self-narrative than one interpreted as resilience. The same event, different story—different self.

Memory: The Fabric of Identity

One of the most powerful threads in the tapestry of identity is memory. Your past—how you recall it, how you interpret it—shapes the person you believe yourself to be.

We often think of memory as a recording device, faithfully storing our experiences. But that’s not how the brain works. Memory is reconstructive, not reproductive. Every time you recall an event, your brain rebuilds it from scattered neural traces. It fills in gaps, edits details, adds new interpretations.

This is why your sense of identity can shift over time. You’re constantly re-editing your internal autobiography, consciously or not. As you change, the lens through which you view the past changes too. And your brain—more novelist than historian—revises accordingly.

In profound cases, memory loss can erase large pieces of identity. People with Alzheimer’s or amnesia often struggle with a fading sense of self—not just because they forget facts, but because they lose the emotional anchor points of who they are.

In contrast, people who survive trauma often reorganize their identity around those memories, forging new strength or narratives of survival. Our memories, fragile as they are, become the scaffolding of our personal identity.

The Social Mirror: How Others Shape You

No one becomes a person alone.

From infancy, your identity is shaped in relationship. The moment a parent calls your name, mirrors your smile, soothes your cries—you begin to form a self in the context of others. You learn who you are by how others respond to you.

Psychologist Charles Horton Cooley coined the term “the looking-glass self” to describe this phenomenon. We see ourselves reflected in the reactions of others. If you’re treated as competent, loved, or funny, you’re more likely to internalize those traits. If you’re ignored, criticized, or abused, you may incorporate those reflections instead.

Even our values and beliefs are not formed in a vacuum. Our families, cultures, religions, schools, and media all leave their imprint. They teach us what matters, what’s admirable, what’s shameful. Over time, these messages—sometimes subtle, sometimes stark—congeal into the lens through which we see ourselves.

Identity, then, is partly constructed socially. It exists not only in your mind, but in the relational web that surrounds you. This doesn’t mean you’re just a product of your environment. But it does mean your sense of “I” is in constant dialogue with “we.”

The Masks We Wear: Roles and Selves

You are a child. A friend. A teacher. A gamer. A parent. A stranger on a bus. A patient in a waiting room. A leader at work. A romantic partner. A follower online.

At any moment, you might play dozens of roles—and each of these roles comes with expectations, behaviors, and emotional tones. Psychologists call these “self-schemas”—internalized ideas about who you are in different contexts.

What’s fascinating is that each role may activate different aspects of your personality. You might be assertive at work but shy at parties. Compassionate with your kids but competitive on the soccer field. The self, it turns out, is contextual.

Are you being fake? No. You’re being fluid. Human beings are not statues—they are rivers. And within this flow, there is a core—a throughline of values, preferences, and themes that feels consistently “you.”

The danger comes not from having many selves, but from losing the ability to integrate them. When people feel forced to hide large parts of who they are—due to stigma, trauma, or cultural pressure—the result can be dissonance, distress, even identity crisis.

Culture and the Collective Self

Where you grow up doesn’t just shape what language you speak or what food you eat. It shapes how you define yourself.

In individualistic cultures like the U.S. or much of Western Europe, identity is often seen as internal, unique, self-expressive. You are “your own person.” Life is a journey of self-discovery.

In collectivist cultures like Japan, India, or many Indigenous societies, identity is more relational. The self is not a bounded individual, but a node in a network. Life is a process of fitting harmoniously into the whole.

Neither view is right or wrong. Each reflects different truths about human nature. But they influence everything—from how we define success, to how we handle conflict, to what stories we tell about ourselves.

Understanding cultural identity is especially crucial in a globalized world. As people move between nations, languages, and values, many develop bicultural or multicultural identities, blending elements from different traditions into something uniquely their own.

The Digital Self: You, Online

In the 21st century, a new frontier of identity has emerged: the digital self.

Every time you post a photo, write a tweet, like a video, or update a status, you are curating an image of who you are. Social media platforms are not just communication tools—they are identity laboratories.

For some, the digital world offers freedom. A place to explore gender, reinvent oneself, or connect with like-minded communities. For others, it becomes a performance trap—where the pressure to present a perfect, polished version of self leads to anxiety and disconnection.

What’s striking is that even the absence of digital presence can shape identity. People who deliberately unplug often report a clearer sense of self—not because they’ve escaped identity, but because they’ve escaped performance.

The online self is not separate from the offline self—it’s an extension. But managing this dual identity can be complex, especially for young people still forming their core sense of who they are.

Gender, Race, and the Politics of Identity

No discussion of identity is complete without acknowledging the deeply political and social aspects of how we define ourselves. Your gender, race, sexual orientation, and ethnicity are not just personal traits—they’re social categories that carry real consequences.

People who are marginalized because of these identities often face pressure to suppress, hide, or defend who they are. Yet, paradoxically, many find great strength and pride in these same identities. Communities form. Movements rise. Culture flourishes.

Psychologists have found that a strong, positive group identity—whether based on race, gender, or sexuality—can foster resilience, self-esteem, and belonging. Conversely, internalized oppression can lead to shame, fragmentation, and alienation.

This is why identity is not just an academic topic—it’s a moral one. A political one. How society treats different identities affects how people come to see themselves. To affirm someone’s identity is not just to validate their experience, but to honor their humanity.

Change, Growth, and the Fluid Self

Here’s a strange but liberating truth: you are not the same person you were five years ago.

Your interests have shifted. Your beliefs may have evolved. Even your personality traits—once thought stable—can and do change. This is the beauty of identity. It’s not fixed in stone. It’s alive.

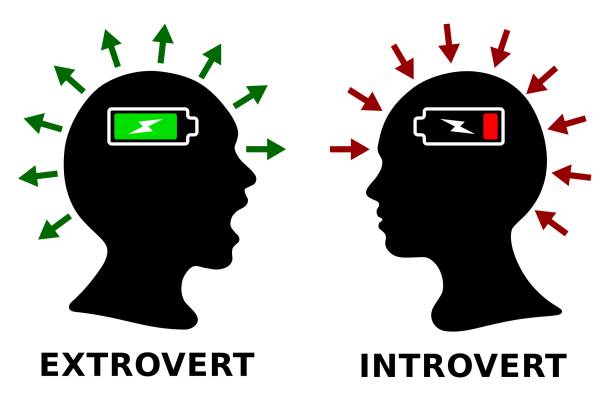

Personality psychologists now agree that while traits like introversion or conscientiousness are relatively stable, they can shift due to life experiences, relationships, therapy, or intentional effort.

Likewise, identity can evolve. People change careers, convert religions, come out, go back to school, start over. Identity, in this sense, is not a prison—it’s a palette.

And science supports this. Neuroplasticity shows that the brain remains malleable well into adulthood. Your “you” is a work in progress, not a final draft. And that’s something to celebrate, not fear.

Who Are You, Really?

So—what makes you “you”?

It’s not just your memories. Or your brain patterns. Or your Instagram handle. Or your gender. Or your culture. Or your name.

It’s all of it. And more.

You are a story told by neurons and nurtured by love. You are a patchwork of roles and a symphony of experiences. You are shaped by your past but not bound by it. You are many selves, cohering into a mosaic of meaning.

You are not a thing. You are a becoming.

And every time you ask the question, “Who am I?”—you invite the answer to unfold.