Happiness is one of the most universal yet elusive concepts in human life. Every person desires it, societies strive to cultivate it, and philosophers, psychologists, and scientists have spent centuries trying to define and measure it. It is a state that influences how we live, how we relate to others, and even how our bodies function. But what exactly is happiness? Is it a fleeting emotion, a state of mind, or something deeper—a lasting sense of fulfillment?

In modern times, happiness has evolved from a philosophical question to a subject of scientific investigation. Researchers from psychology, neuroscience, sociology, and even economics have explored what makes people happy, how happiness affects health and behavior, and whether it can be cultivated intentionally. The science of happiness, often called “positive psychology,” does not merely study what goes wrong in human life but focuses on what goes right—what allows people to flourish.

Happiness is not just a luxury or an abstract idea. It is a measurable state of mental and physical well-being that profoundly affects our health, longevity, and social functioning. From brain chemistry to cultural norms, from individual mindset to societal systems, happiness is shaped by an intricate web of biological, psychological, and environmental factors.

The Meaning and Nature of Happiness

The concept of happiness has existed for as long as human thought. In ancient philosophy, happiness was often regarded as the ultimate goal of life—the summum bonum, or highest good. For Aristotle, happiness (or eudaimonia) was not simply pleasure but a state of flourishing that comes from living virtuously and realizing one’s potential. For the Epicureans, it was the pursuit of pleasure and the avoidance of pain, but in a balanced and thoughtful way. The Stoics saw happiness as living in harmony with nature and reason, being free from destructive emotions.

In modern psychology, happiness is generally understood as a combination of positive emotion and life satisfaction. It involves both short-term feelings—like joy, gratitude, or amusement—and long-term assessments of one’s life as meaningful and fulfilling. Psychologists often distinguish between two kinds of happiness: hedonic and eudaimonic.

Hedonic happiness refers to pleasure, enjoyment, and comfort—the immediate experiences that make us feel good. Eudaimonic happiness, on the other hand, stems from living according to one’s values, pursuing purpose, and developing one’s full potential. While hedonic happiness provides short bursts of joy, eudaimonic happiness leads to deeper fulfillment and psychological growth.

Both forms of happiness are important, and most people experience a blend of them throughout life. Scientific studies suggest that sustainable happiness often arises from a balance between pleasure and purpose.

The Biological Basis of Happiness

At its core, happiness is not only a psychological experience but also a biological one. It involves complex interactions among brain structures, neurotransmitters, hormones, and the body’s overall physiology. The sensation of happiness arises from activity in certain areas of the brain, particularly those involved in reward, emotion regulation, and motivation.

The limbic system, especially the amygdala and the hippocampus, plays a key role in processing emotions. The prefrontal cortex helps regulate emotional responses and contributes to feelings of satisfaction and meaning. Meanwhile, the brain’s reward pathways—centered around the neurotransmitter dopamine—are directly linked to pleasure, motivation, and learning.

When we experience happiness, several chemicals surge in the brain. Dopamine creates feelings of reward and drives goal-seeking behavior. Serotonin stabilizes mood and contributes to a sense of calm and well-being. Endorphins reduce pain and induce euphoria, while oxytocin, often called the “love hormone,” strengthens social bonding and trust.

These neurochemical systems evolved to encourage behaviors that enhance survival and reproduction. For example, social cooperation, caregiving, and forming close relationships trigger oxytocin release, strengthening social groups. Similarly, the dopamine system reinforces actions that are rewarding, such as eating or achieving goals.

However, happiness is not a constant state of chemical pleasure. The brain naturally adapts to positive experiences—a phenomenon known as “hedonic adaptation.” After a joyful event, such as a promotion or a vacation, people tend to return to their baseline level of happiness over time. This adaptation ensures stability but also makes happiness fleeting unless one cultivates deeper, more sustainable sources of fulfillment.

The Psychology of Happiness

Psychologically, happiness involves the interplay of emotions, thoughts, personality, and perception. It is not merely the absence of negative feelings but a positive state that includes joy, contentment, love, and a sense of meaning.

Research in positive psychology, pioneered by Martin Seligman and Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, has identified key elements that contribute to human flourishing. These include positive emotions, engagement, relationships, meaning, and accomplishment—a framework known as the PERMA model. Each component contributes differently to overall well-being.

Positive emotions broaden our awareness and build psychological resources. Engagement refers to the state of “flow,” where one is fully absorbed in an activity that challenges but also matches one’s skills. Meaning arises from belonging to and serving something greater than oneself. Positive relationships provide social support, empathy, and love, which are essential for emotional health. Accomplishment gives a sense of mastery and purpose.

Personality also influences happiness. Traits such as extraversion, optimism, and openness to experience are consistently associated with higher well-being. Meanwhile, chronic pessimism or neuroticism tends to lower happiness. But personality is not destiny; people can learn cognitive and behavioral strategies to increase happiness regardless of temperament.

Cognitive theories of happiness emphasize that perception matters more than external circumstances. What we think about our experiences—how we interpret events, set expectations, and focus our attention—has a greater impact on happiness than the events themselves. Practices such as gratitude, mindfulness, and cognitive reframing help individuals train their minds to focus on the positive and handle challenges more resiliently.

The Role of Environment and Society

While happiness has internal psychological and biological roots, it is also deeply influenced by external factors—family, culture, economy, and community. Human beings are social creatures; we thrive on connection, cooperation, and belonging. The social environment can either support or hinder happiness.

Strong social ties are among the most reliable predictors of well-being. People with close friendships, supportive families, or loving relationships tend to be happier, healthier, and live longer. Loneliness and social isolation, by contrast, are linked to depression, anxiety, and even physical illness.

Economic and societal conditions also play a role. Poverty, inequality, and job insecurity can undermine happiness by creating chronic stress and limiting opportunities for growth. However, beyond a certain threshold of income—sufficient to meet basic needs—additional wealth contributes less to happiness. Studies have shown that after people reach a level of comfort and security, relationships, purpose, and personal growth become far more important than material possessions.

Culture shapes how happiness is defined and pursued. In individualistic cultures, happiness is often associated with personal achievement and self-expression. In collectivist cultures, it may be linked more to social harmony and community belonging. Despite these differences, universal elements—such as love, gratitude, and meaning—transcend cultural boundaries.

Public policies can also affect collective happiness. Countries that prioritize social welfare, education, healthcare, and equality consistently report higher average well-being. The World Happiness Report, which measures happiness globally, often ranks nations like Finland, Denmark, and Iceland at the top—societies known for strong social trust, low corruption, and supportive institutions.

Measuring Happiness Scientifically

Happiness may seem subjective, but scientists have developed methods to study it objectively. Psychologists use self-report surveys, behavioral observations, and physiological indicators to assess well-being.

Commonly used tools include the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS), the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS), and the Oxford Happiness Questionnaire. These instruments ask people to evaluate their emotions, satisfaction, and sense of meaning.

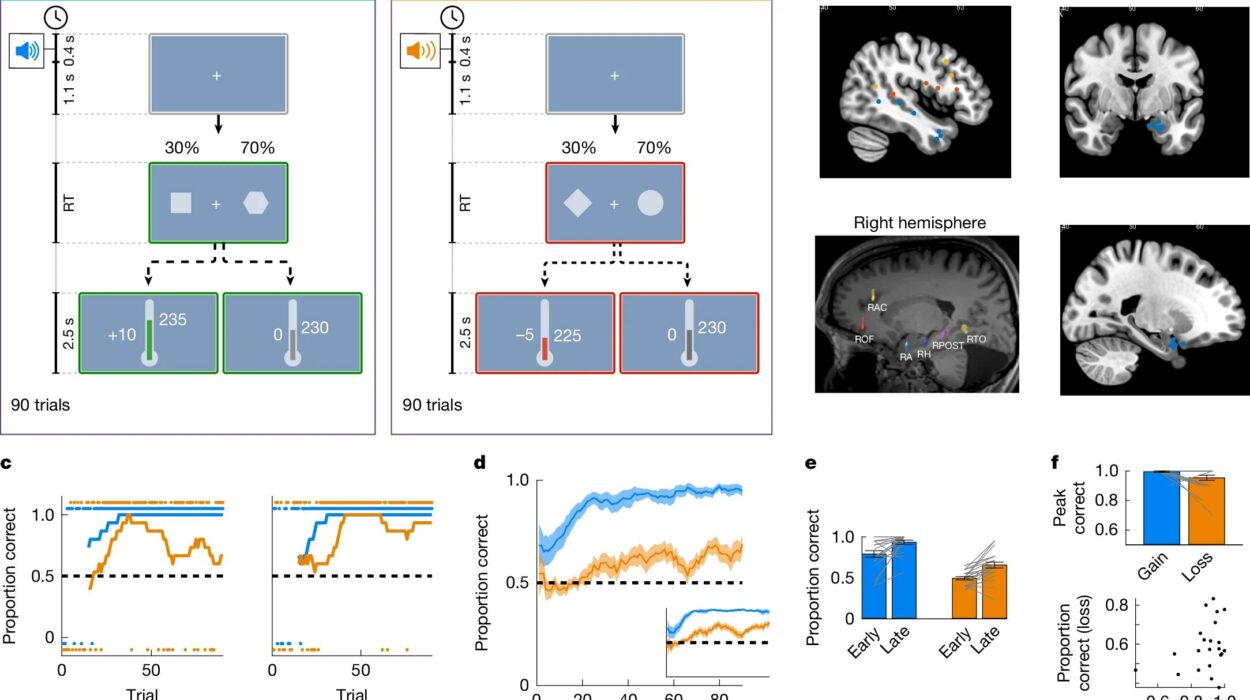

In neuroscience, brain imaging techniques such as functional MRI allow researchers to study the neural correlates of happiness. For example, increased activity in the left prefrontal cortex is associated with positive emotions and approach motivation. Hormonal and immune markers also provide insights into how psychological well-being affects physical health.

Large-scale surveys, such as the World Happiness Report, use data on income, social support, life expectancy, freedom, trust, and generosity to rank nations by average happiness. These studies help governments and organizations understand which social and economic factors contribute most to well-being.

Although measuring happiness is challenging because of its subjective nature, scientific approaches provide valuable insights that help policymakers, clinicians, and individuals make informed decisions to promote mental and social health.

The Relationship Between Happiness and Health

Happiness and health are deeply intertwined. Numerous studies show that happier people tend to live longer, experience fewer illnesses, and recover faster from disease. Positive emotions strengthen the immune system, lower stress hormones, and improve cardiovascular function.

Chronic unhappiness, on the other hand, is associated with increased inflammation, higher blood pressure, and a greater risk of mental disorders such as depression and anxiety. The mind-body connection is a powerful pathway through which emotions affect physical health.

Psychological well-being also promotes healthier behaviors. People who feel happy are more likely to exercise, eat nutritious food, get sufficient sleep, and avoid harmful habits such as smoking or substance abuse. Moreover, happiness improves social relationships, which in turn provide emotional and practical support that further enhances resilience and recovery.

The biological mechanisms underlying the happiness-health link involve multiple systems. Reduced stress decreases cortisol production, while positive emotions stimulate the release of endorphins and strengthen immune defenses. Over time, these effects accumulate, contributing to longer and healthier lives.

The Role of Genetics and Individual Differences

Genetic studies suggest that about 30% to 50% of the variation in individual happiness is heritable. This means some people are naturally predisposed to higher or lower levels of baseline happiness due to their genetic makeup.

Twin studies have shown that even when identical twins are raised apart, their happiness levels are often more similar than those of fraternal twins raised together. Genes influence traits such as temperament, optimism, and sensitivity to stress, all of which contribute to subjective well-being.

However, genetics is not destiny. While some people may have a “happier” disposition, environmental factors and personal choices play a significant role. Life circumstances, relationships, habits, and attitudes can modify one’s happiness set point. Intentional activities—like practicing gratitude, meditation, and kindness—can significantly increase happiness over time.

This interaction between nature and nurture underscores that happiness is both inherited and learned. The brain’s neuroplasticity—the ability to form new neural connections—means that people can literally “rewire” their brains through positive experiences and habits.

Happiness Across the Lifespan

Happiness changes throughout life, following patterns influenced by age, experience, and life circumstances. Research shows that happiness often follows a U-shaped curve: high in youth, dipping during middle age, and rising again in later life.

Young adults experience happiness through exploration, relationships, and identity formation. Middle-aged individuals often face stress from career, family, and financial pressures, which can temporarily lower well-being. However, older adults tend to report greater life satisfaction despite physical decline, possibly due to increased emotional regulation, acceptance, and gratitude.

Happiness in old age is closely linked to social connection, purpose, and mental health. Elderly individuals who maintain strong relationships, engage in meaningful activities, and retain a sense of autonomy tend to experience high well-being. Conversely, loneliness and social isolation are major risk factors for unhappiness and cognitive decline in aging populations.

The Philosophy of Happiness

Beyond science, happiness has always been a central theme in philosophy. Ancient Greek philosophers viewed it as the ultimate aim of human existence. In Buddhism, happiness arises from detachment from desire and understanding the impermanence of life. In Western thought, Enlightenment philosophers such as John Locke and Thomas Jefferson linked happiness to liberty, seeing it as a fundamental human right.

Modern existential and humanistic philosophers, such as Viktor Frankl, argue that meaning and purpose are the deepest sources of happiness. According to Frankl, happiness cannot be pursued directly; it ensues naturally when a person dedicates themselves to something greater than self-interest.

Philosophical traditions across cultures converge on one idea: happiness is not merely a temporary pleasure but a way of being that involves balance, virtue, and awareness.

Can Happiness Be Taught or Cultivated?

Scientific research strongly suggests that happiness can be increased through intentional practice. While circumstances and genetics play roles, habits of thought and behavior are powerful determinants of well-being.

Positive psychology interventions—such as gratitude journaling, meditation, acts of kindness, and savoring positive experiences—have been shown to increase happiness and reduce depression. Mindfulness-based programs enhance emotional regulation, while cognitive-behavioral strategies help people reframe negative thoughts and build optimism.

Social connection is one of the strongest predictors of lasting happiness. Engaging with others, showing empathy, and building supportive communities nurture both personal and collective well-being. Purpose-driven work, creativity, and volunteering also enhance happiness by fulfilling the human need for meaning.

The key is consistency. Just as physical fitness requires regular exercise, emotional well-being requires daily mental and emotional practice. Happiness is a skill that can be strengthened with attention, gratitude, and compassion.

The Global Pursuit of Happiness

In recent decades, the idea of measuring national well-being has gained global attention. Governments and organizations are increasingly recognizing that economic growth alone does not guarantee happiness. Indicators such as the Gross National Happiness (GNH) index, pioneered by Bhutan, or the United Nations World Happiness Report, emphasize social and emotional factors alongside economic metrics.

These efforts reflect a growing awareness that happiness should be a central goal of public policy. Access to healthcare, education, equality, and justice all contribute to collective well-being. Nations that promote trust, freedom, and social cohesion consistently achieve higher levels of happiness among citizens.

The global study of happiness has also revealed interesting cultural variations. In some societies, happiness is viewed as a communal experience rather than an individual pursuit. In others, expressions of happiness may be restrained due to cultural norms valuing humility or harmony. Despite these differences, the desire for happiness remains universal—a shared thread connecting all of humanity.

The Future of Happiness Science

The scientific study of happiness continues to evolve, integrating insights from psychology, neuroscience, genetics, and artificial intelligence. Researchers are now exploring how technology affects well-being—both positively, through connection and education, and negatively, through social comparison and digital addiction.

Advances in brain imaging and computational modeling may soon allow personalized happiness interventions, tailored to individual biology and psychology. Moreover, as society faces global challenges such as climate change, inequality, and technological disruption, the science of happiness may play a vital role in designing more compassionate and sustainable systems.

The future of happiness lies not in the pursuit of constant pleasure, but in building meaningful lives, supportive communities, and a balanced relationship with the planet.

Conclusion

Happiness is both a feeling and a state of being—a blend of pleasure, meaning, connection, and growth. It is shaped by biology, mind, relationships, and environment. While it can be influenced by genetics and life circumstances, it is not beyond our control. Through mindfulness, gratitude, kindness, and purpose, humans can nurture lasting well-being.

Science has shown that happiness is not a random gift but a process—one that involves intentional living and awareness. It is the essence of what makes life worth living, a measure not just of pleasure but of depth, virtue, and fulfillment.

To be happy is to live fully—to experience joy, love, and wonder, to grow from pain, and to connect with others and the world in meaningful ways. Happiness, ultimately, is not just the goal of life; it is the art of living itself.