Somewhere in the Milky Way, just 60 light-years from Earth, a cold and lonely giant circles its star in an orbit shaped like a stretched football. Temperatures on this massive world barely rise above freezing. Its atmosphere churns with chemical chaos. And now, thanks to NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope, we can finally see it.

The planet—14 Herculis c—has been called strange, abnormal, and even chaotic by astronomers. But this week, it became something else: visible.

For the first time, scientists have directly imaged 14 Herculis c, one of only two known planets orbiting the star 14 Herculis, and one of the coldest exoplanets ever captured by telescope. This alien world, about seven times the mass of Jupiter, orbits a star much like our Sun—but everything about its neighborhood feels a bit… off.

“The colder an exoplanet, the harder it is to image,” said William Balmer, co-first author of the new study and a graduate student at Johns Hopkins University. “This is a totally new regime of study that Webb has unlocked with its extreme sensitivity in the infrared.”

The discovery was announced Tuesday at the 246th meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Anchorage, Alaska. The findings are being submitted to The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

A Planet in the Shadows

In a universe teeming with nearly 6,000 confirmed exoplanets, few have ever been directly photographed. Most are spotted indirectly—by the way they dim a star’s light or tug on it with their gravity. Direct imaging, especially of cold exoplanets like 14 Herculis c, is like trying to photograph a glowing ember from across a city. It’s dim. It’s distant. It’s drowned in light from its nearby star.

But the James Webb Space Telescope isn’t just any telescope.

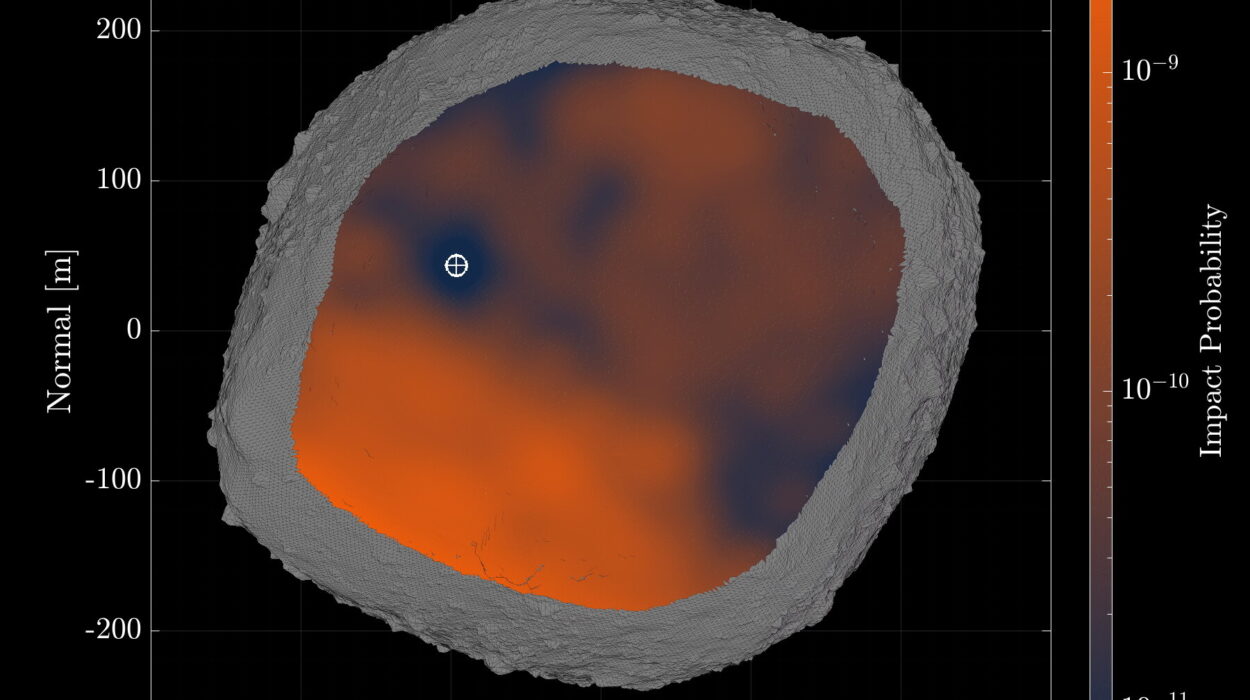

Using its Near-Infrared Camera (NIRCam) and a coronagraph—a device that blocks out starlight—Webb was able to spot the faint dot of light that is 14 Herculis c. Its temperature? A frosty 26°F (–3°C), making it among the coldest exoplanets ever imaged.

That temperature, however, is deceiving. Because while this world may be chilly, the system it inhabits is far from calm.

When Planetary Orbits Collide

In our solar system, planets trace gentle, flat ellipses around the Sun like dancers on a well-choreographed stage. But in the 14 Herculis system, it’s more like a cosmic wrestling match.

There are two known planets here—14 Herculis b, which is closer to the star and hidden by the coronagraph in Webb’s image, and 14 Herculis c, the newcomer to our eyes. But what sets them apart isn’t just their size or distance—it’s their orbits. They crisscross in space, tilted at an extraordinary 40-degree angle from each other. If you imagine their paths, they form a tilted “X,” with the star glowing at the heart of the tangle.

This isn’t normal. And scientists believe it’s the result of planetary violence.

“The early evolution of our own solar system was dominated by the movement and pull of our own gas giants,” Balmer explained. “Here, we are seeing the aftermath of a more violent planetary crime scene.”

According to one leading theory, 14 Herculis once hosted a third planet. But early in the system’s chaotic childhood, it may have been flung outward—violently ejected into interstellar space. In the process, the surviving planets were sent spinning into misaligned, unpredictable orbits.

It’s a cosmic crime drama written across the sky—and we’re just now beginning to read the clues.

A Cold Giant with a Churning Heart

14 Herculis c doesn’t just intrigue scientists because of its orbit. What’s inside the planet—and what’s happening in its atmosphere—is equally mysterious.

Orbiting about 1.4 billion miles from its star (roughly 15 times farther than Earth is from the Sun), the planet takes a long, lopsided route around its host. Its orbit is elliptical, not circular—like a distorted football spiraling through space. This highly eccentric journey affects everything from its climate to its visibility.

But the real surprise came from how dim the planet appeared in the infrared light Webb detected. Based on its mass, age (about 4 billion years), and expected temperature, scientists predicted it would shine brighter. Instead, it was fainter—much fainter.

“We’re seeing less light than we expected,” said Daniella C. Bardalez Gagliuffi of Amherst College, co-first author with Balmer. “That usually means something unusual is going on in the atmosphere.”

And something is.

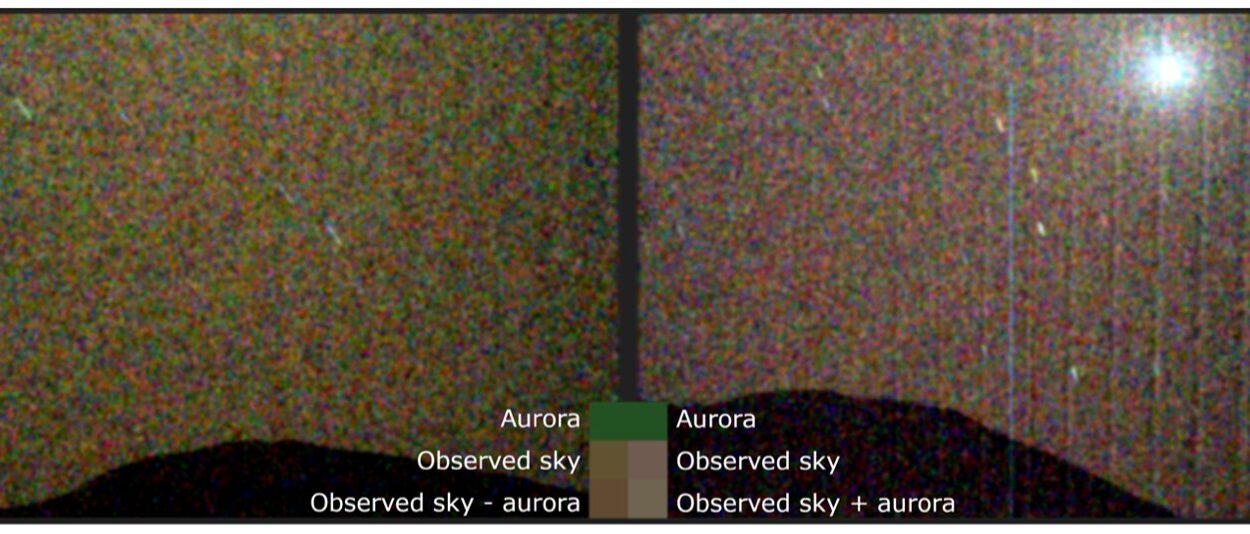

Instead of seeing methane—common in cold gas giants like Neptune—scientists detected signs of carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide, chemicals that shouldn’t dominate at such low temperatures. What gives?

The answer may lie in a process called disequilibrium chemistry. Just like stormy oceans churn up nutrients from the deep, 14 Herculis c’s atmosphere seems to mix its layers rapidly. Hotter molecules from deep below rise quickly to the surface before they can cool and settle. It’s a signature often seen in brown dwarfs, the “failed stars” that blur the line between planet and sun.

“This exoplanet is so cold, the best comparisons we have that are well-studied are the coldest brown dwarfs,” Bardalez Gagliuffi explained. “It’s an exciting bridge between types of objects we’ve studied separately until now.”

A New Chapter in Planet Hunting

To the naked eye, 14 Herculis c is just a tiny dot in a sea of infrared light. But for astronomers, it’s a window into a new era. Most directly imaged exoplanets until now have been hot, young, and glowing—easy targets. But 14 Herculis c is different. It’s older. Colder. Quieter. And that makes it a symbol of what’s now possible with Webb.

“This is only the beginning,” Balmer said. “Webb is going to let us build a more complete catalog—not just of blazing hot gas giants, but of all kinds of planets, in all kinds of systems.”

Future observations of 14 Herculis c will likely include spectroscopy, which can identify the planet’s specific atmospheric gases. That will help scientists refine their understanding of how it formed, how it evolved, and what forces still shape it.

More broadly, this discovery is a reminder of the messiness of planet-making. Our solar system may seem orderly now, but its past was probably turbulent. Jupiter and Saturn once flung debris across the inner solar system, sculpting Earth’s path and possibly even influencing the emergence of life.

By peering at chaotic systems like 14 Herculis, scientists are not just learning about distant stars—they’re reading ancient echoes of our own cosmic origins.

The Quiet Drama of Distant Worlds

There’s something poetic about it: a frozen world, light-years away, slowly circling a star in the aftermath of a planetary brawl—and we, fragile creatures on a small blue dot, finally catching a glimpse.

14 Herculis c may never host life. It may never be visited. But in its orbit and its atmosphere, it carries stories. Of heat and violence. Of chemistry and balance. Of what it means to be a planet in a chaotic universe.

And thanks to the James Webb Space Telescope, we can now witness that drama firsthand.

One pixel at a time.