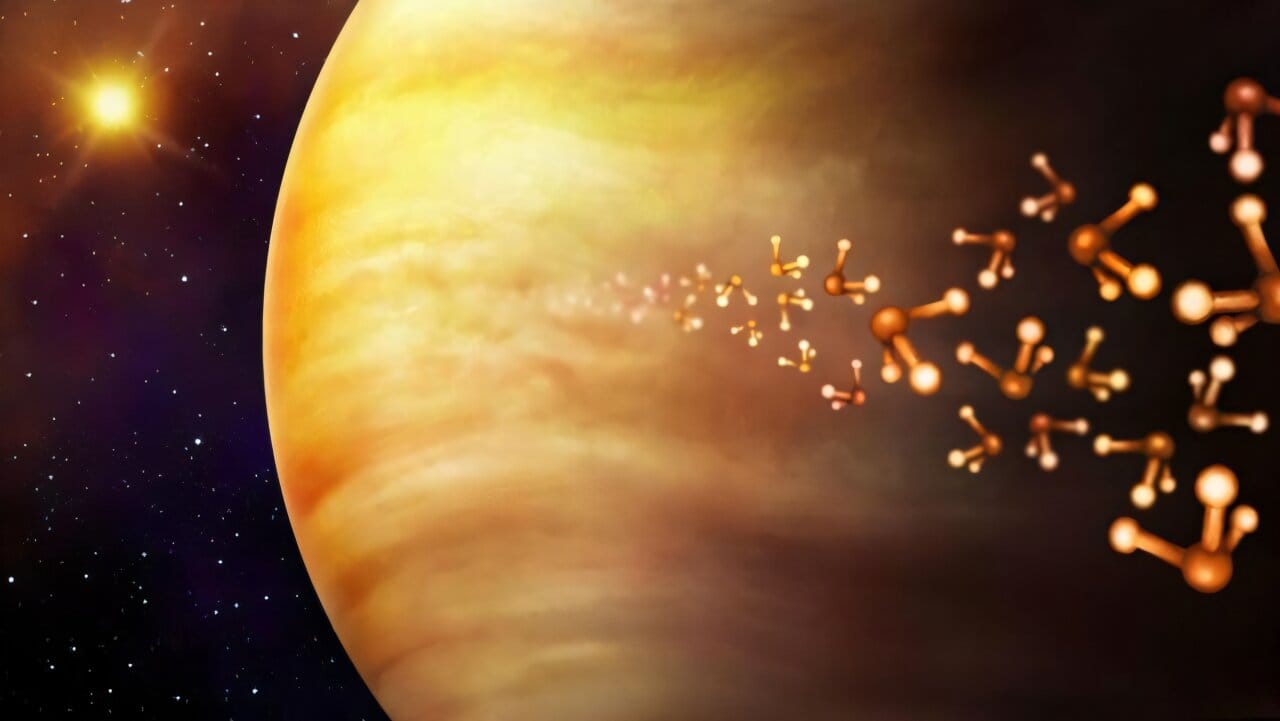

High above the hellish landscape of Venus—where surface temperatures could melt lead and the pressure is enough to crush a submarine—there floats a realm of mystery. In this layer of dense, yellowish clouds, scientists have found chemical whispers that hint at something astonishing: the possible fingerprints of alien life.

Now, a team of UK researchers is determined to discover whether the planet long dismissed as Earth’s “evil twin” might instead be harboring tiny, tenacious microbes in its toxic skies.

Their ambitious mission—announced this week at the Royal Astronomical Society’s National Astronomy Meeting in Durham—could finally answer a question that has gripped planetary scientists and captured the public imagination: Are we alone, or does life cling to the clouds of Venus?

A Tale of Two Gases

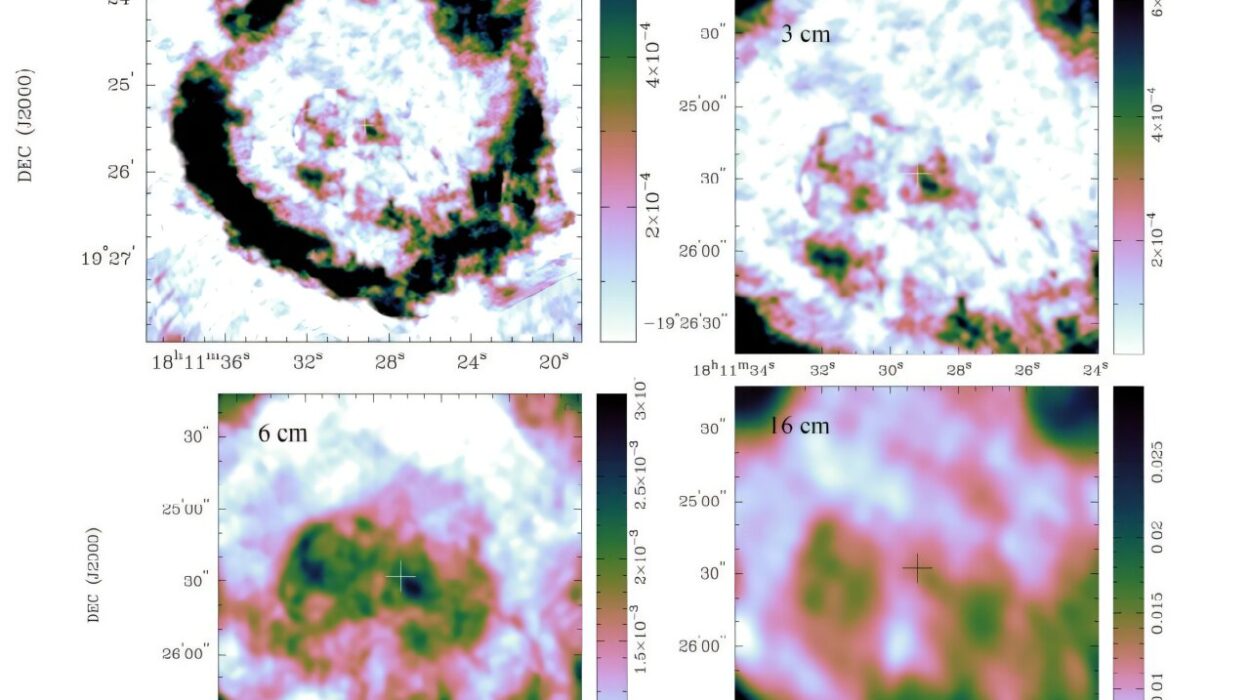

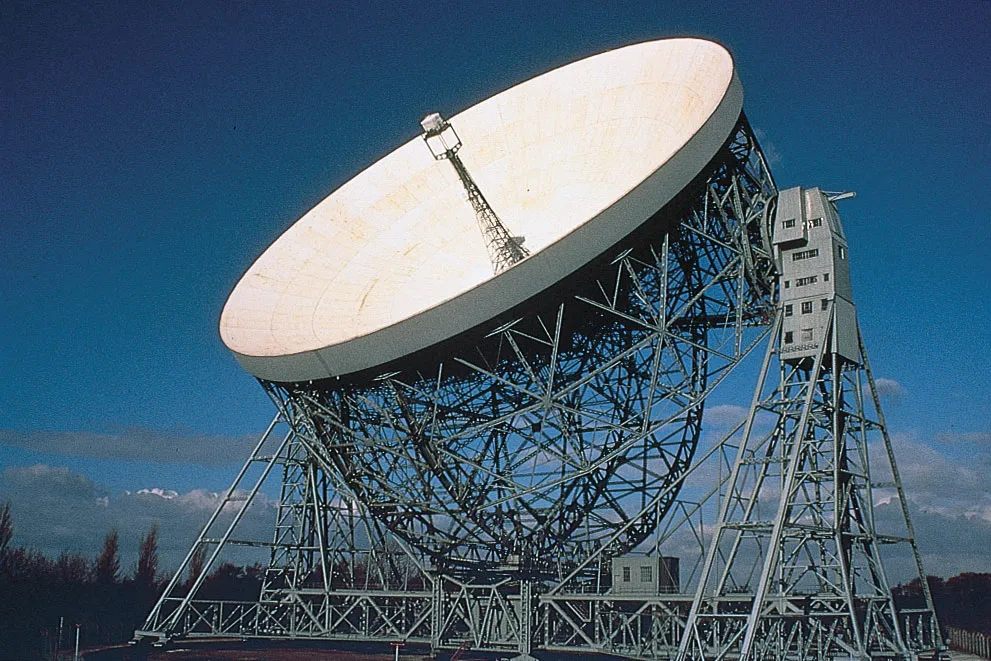

The story begins in 2020, when astronomers using the James Clerk Maxwell Telescope in Hawaii reported detecting phosphine in Venus’s atmosphere. On Earth, this pungent gas is produced almost exclusively by microbes and industrial processes. Phosphine has no easy non-biological explanation, especially in an environment as extreme as Venus.

The discovery set off a firestorm of excitement—and controversy. Follow-up observations struggled to confirm the finding, raising doubts. But the team behind the detection, known as the JCMT-Venus project, pressed on, determined to separate signal from noise.

Over the past five years, they’ve uncovered tantalizing new clues. Phosphine, it turns out, seems to flicker in and out of Venus’s atmosphere, rising and falling with the rhythm of the planet’s day-night cycle. Sunlight appears to destroy it, only for the gas to reappear later.

And phosphine isn’t the only oddity. Another gas—ammonia—has now been tentatively detected as well. Like phosphine, ammonia on Earth is primarily the handiwork of life or industry. In Venus’s clouds, which are laced with sulfuric acid potent enough to strip paint off a spacecraft, ammonia could act as a natural neutralizer, potentially creating tiny havens of less hostile conditions.

“There are no known chemical processes for the production of either ammonia or phosphine,” said Professor Jane Greaves of Cardiff University, who has led the search. “The only way to know for sure what is responsible for them is to go there.”

Into the Acid Veil

Greaves and her colleagues have proposed a new mission concept that could finally resolve the mystery: VERVE—the Venus Explorer for Reduced Vapors in the Environment.

The plan is elegantly audacious. Instead of building a massive flagship spacecraft from scratch, VERVE would take the form of a compact CubeSat—a shoebox-sized probe bristling with specialized instruments—at a cost of around €50 million ($59 million).

VERVE would hitch a ride aboard the European Space Agency’s EnVision mission, scheduled to launch in 2031. Once EnVision arrives at Venus, the CubeSat would detach and slip into the planet’s thick atmosphere, embarking on an independent survey of the gases swirling through the clouds.

Its prime directive: map the distribution of phosphine, ammonia, and other hydrogen-rich compounds that have no known geological or atmospheric sources. If these gases are present in significant quantities, and especially if they cluster in specific regions or layers, it would strengthen the case that some sort of microbial life might be generating them.

“The hope is that we can establish whether the gases are abundant or in trace amounts,” Greaves explained. “And whether their source is on the planetary surface—perhaps from volcanic ejecta—or whether there is something in the atmosphere, potentially microbes.”

The Temperate Twilight Zone

To many, the idea of life on Venus sounds preposterous. After all, the planet’s surface is a searing 450°C (842°F), hot enough to melt zinc. Any Earth-born creature would be obliterated in seconds.

But about 50 kilometers (31 miles) above that inferno lies a curious twilight zone—a band of atmosphere where temperatures hover between 30°C and 70°C (86°F to 158°F), and the pressure is similar to sea level on Earth. In this relatively temperate layer, clouds are made of sulfuric acid droplets, but some scientists argue that extremophile microbes—akin to those that thrive in acid pools and volcanic vents on our planet—might find a way to survive.

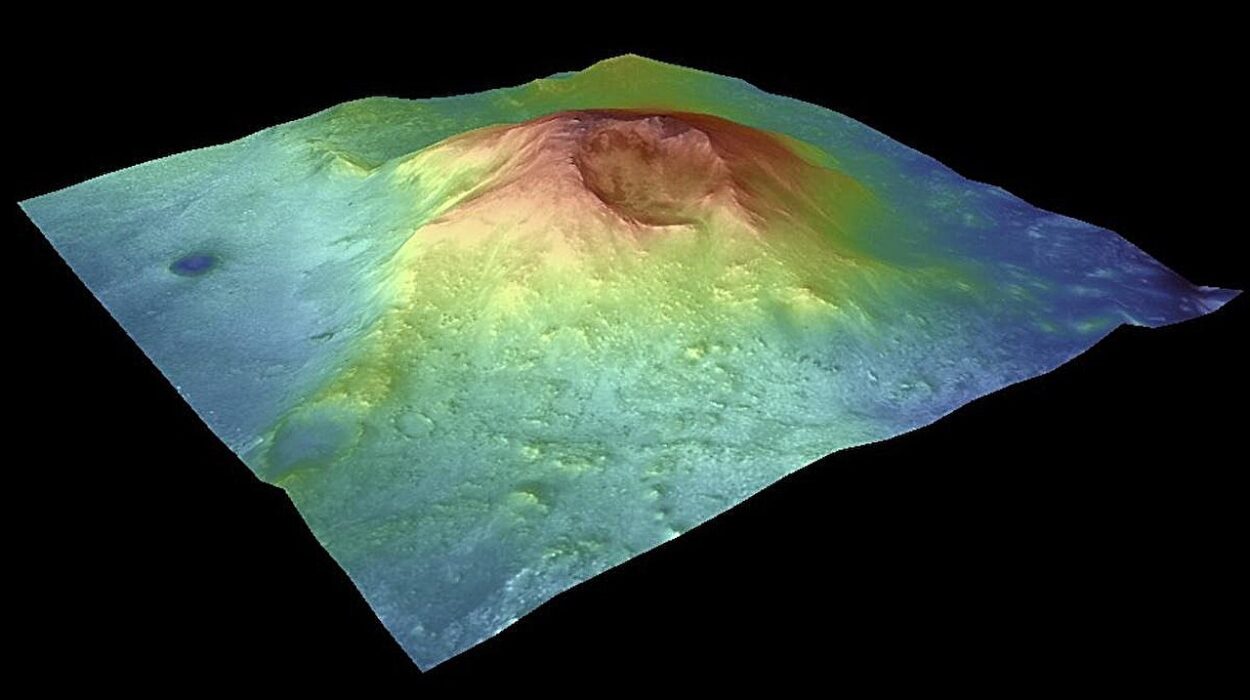

If such life ever existed, it could be the remnant of an earlier, gentler Venus. Billions of years ago, astronomers believe, the planet may have had oceans and a climate not so different from Earth’s. But runaway greenhouse gases transformed Venus into a furnace, boiling away any surface water and choking the atmosphere with carbon dioxide.

It’s possible—just possible—that hardy microbial life retreated upward, evolving to survive in the acid-laced clouds rather than vanishing entirely.

A Controversial Quest

Even within the scientific community, the notion of Venusian life remains deeply polarizing.

Phosphine and ammonia are fascinating clues, but skeptics warn that there could be unknown geological or chemical processes at work, perhaps involving exotic reactions on mineral grains or hidden volcanic activity.

Dr. Dave Clements of Imperial College London, who leads the JCMT-Venus project, believes that the dynamic, ever-changing nature of Venus’s atmosphere might help explain why phosphine observations have been so inconsistent.

“This may explain some of the apparently contradictory studies,” he said. “Many other chemical species—like sulfur dioxide and water—have varying abundances, and may eventually give us clues to how phosphine is produced.”

Resolving this debate requires data that telescopes simply can’t provide. It requires a probe—like VERVE—capable of sampling the clouds directly, measuring the chemistry in real time, and mapping how these gases ebb and flow across Venus’s hidden skies.

An Adventure Worth Taking

While Mars has long been the poster child for extraterrestrial life hunting, Venus is emerging as a compelling—and perhaps even more provocative—target.

After decades of neglect, the planet is finally regaining the attention of space agencies around the world. NASA, ESA, and the Indian Space Research Organisation all have Venus missions in development.

But VERVE stands out for its singular focus on a question as old as science itself: is life unique to Earth, or can it take root in places we once thought uninhabitable?

“We’re on the verge of finding out,” Greaves said. “If there are microbes in the Venusian clouds, they would be a completely new form of life—one that evolved in parallel to life on Earth. That would change everything we know about biology and our place in the universe.”

Waiting for the Answer

As researchers finalize their plans and wait for funding, the clouds of Venus continue to swirl, keeping their secrets for a little longer.

But soon, if all goes well, VERVE will rise on a column of fire, cross the void between worlds, and slip into the acid haze—carrying with it our hopes for one of the most profound discoveries in the history of science.

Until then, we can only look up and wonder whether, in the drifting golden clouds of Earth’s closest planetary neighbor, something tiny and ancient is looking back.

More information: VERVE—a proposal for an ESA mini-Fast mission to Venus, conference.astro.dur.ac.uk/eve … 7/contributions/462/