The materials we encounter in our everyday life are as varied as their functions. A dry material can make an excellent fire starter, whereas a soft material is well-suited for creating sweaters. Batteries rely on materials capable of storing significant energy, while microchips require materials that can precisely control the flow of electricity. The underlying properties of these materials — what makes them good conductors, insulators, or heat-resistant — are deeply rooted in their atomic structures, which dictate how they interact with the world around them. At the atomic level, the arrangement of particles forms intricate patterns, often with multiple competing configurations. This atomic structure governs how a material behaves under different conditions, including interactions with light, electricity, and other materials.

Scientists at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Argonne National Laboratory, alongside collaborators from universities and other national laboratories, have turned their focus to a fascinating class of materials with remarkable properties. These materials undergo significant changes when exposed to an ultrafast pulse of laser light, entering a temporary and exciting state outside of equilibrium — a phenomenon known as metastability. These discoveries, though still in the experimental stage, could pave the way for innovations in how we store and process information in future electronic devices. Their research, published in Nature Materials, explores how materials can persist in these unusual, highly reactive states and what this means for the field of material science.

Metastable States: A New Frontier in Material Science

Metastable states represent an exciting frontier for material scientists. Unlike most materials, which remain stable in their lowest energy state (or equilibrium), metastable states persist beyond equilibrium, even though they may not be the most energetically favorable configuration for the material. The search for these states is driven by the recognition that such materials may possess unique and unexpected properties — potentially unlocking new applications, especially in fields like electronics, data storage, and memory technology.

A well-known example of a metastable state is diamond, a form of carbon. While graphite, another form of carbon, is energetically more stable, diamonds exist in a metastable state, maintaining their structure for millions of years, despite the fact that they could eventually decay into graphite under natural conditions. Metastable states can be thought of like a ball perched on a ledge—while gravity wants it to fall to the ground (the stable state), an obstacle blocks the path, allowing the ball to temporarily stay in its high-energy state.

The challenge for researchers is that most metastable states are fleeting. However, some metastable states can persist long enough to be of practical use, making them ideal candidates for the kind of technological advancements that push the limits of current materials. The work conducted at Argonne National Laboratory involves these persistent nonequilibrium states, exploring how materials can be driven into such states through the application of external forces such as light or pressure.

Ferroelectrics and the Role of Ultrashort Laser Pulses

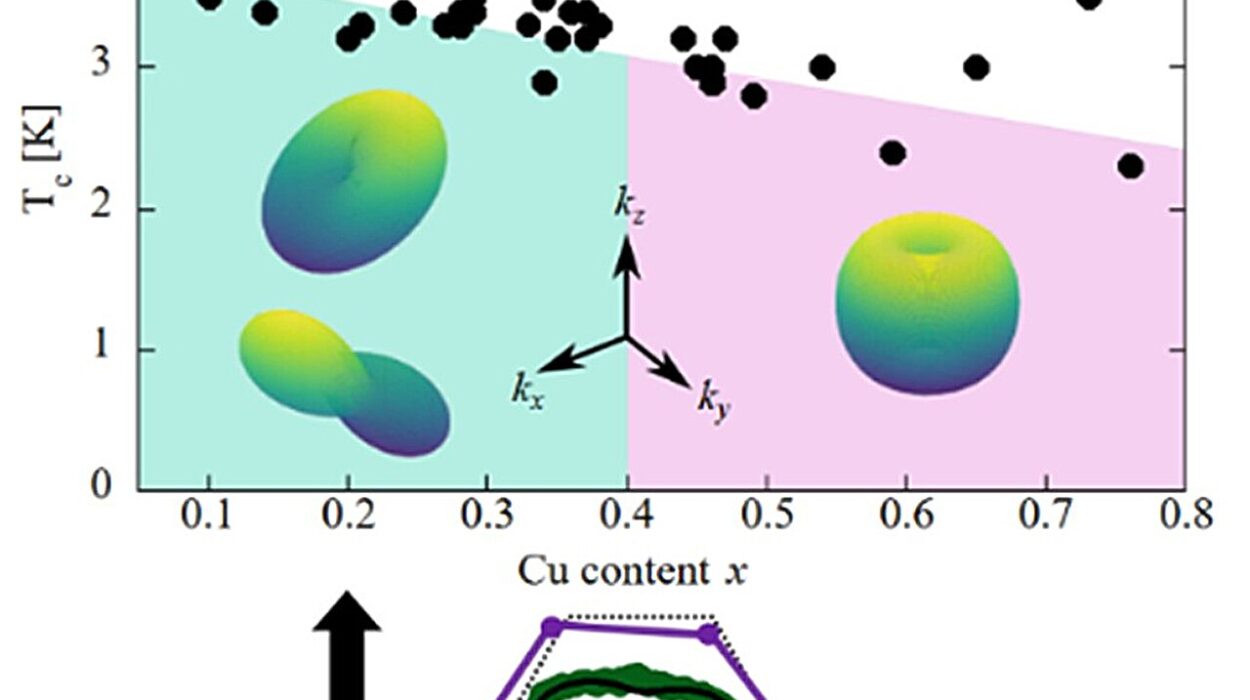

A primary focus of the research is understanding metastability in ferroelectric materials. Ferroelectrics are a class of materials that can retain electric polarization even in the absence of an external electric field. These materials are integral to applications like memory storage, actuators, and sensors. By harnessing metastable states, it might be possible to develop new materials for more efficient and densely packed electronics, potentially transforming fields ranging from computing to artificial intelligence.

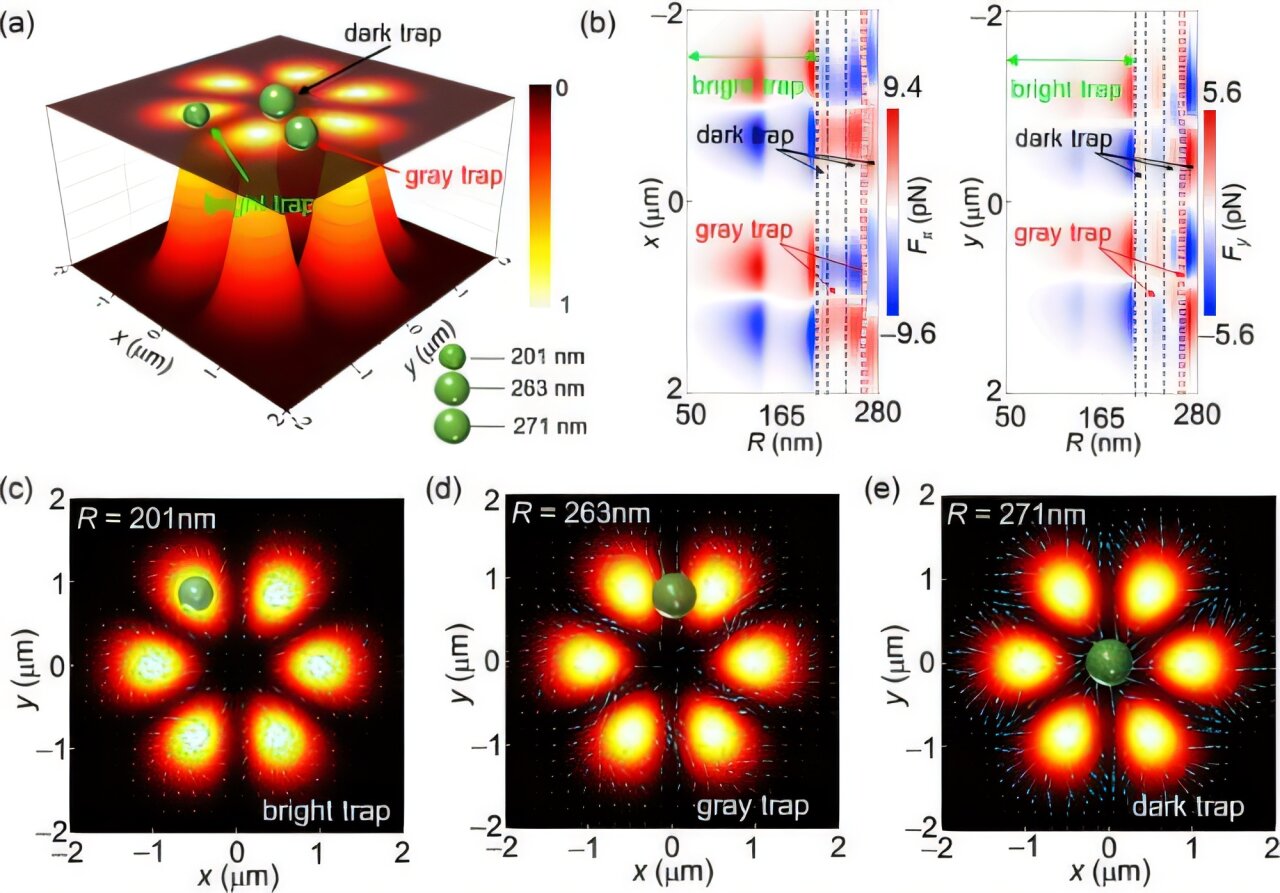

In a series of groundbreaking experiments, the scientists utilized extremely short laser pulses to induce a phase transition in a material known for its complex atomic structure. The material consists of alternating layers of two different materials — a ferroelectric and a nonferroelectric. These layers have opposing electron arrangements, creating a “frustrated” electronic structure that limits the material’s ability to relax into a stable equilibrium. This electron frustration creates a unique situation where the material can access metastable states, much like the proverbial ball stuck on the ledge.

Using Lasers to Unlock Hidden Properties

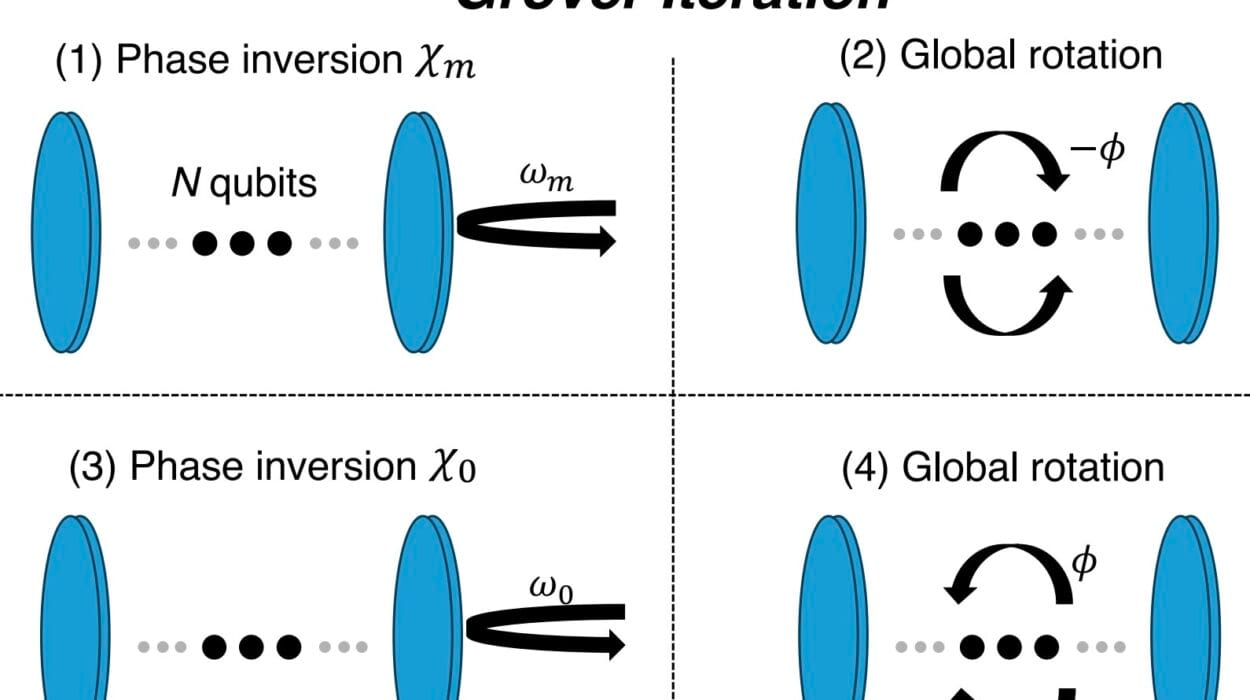

To investigate how materials move in and out of these metastable states, the team used ultrafast laser pulses, each lasting less than 100 femtoseconds, to excite the material. A femtosecond is a quadrillionth of a second, and the scale of these experiments is extraordinarily small in both time and space. To put this in perspective, the difference between one second and a femtosecond is comparable to the difference between 30,000 years and the blink of an eye.

The team collaborated with top-tier X-ray free-electron laser facilities, such as the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) at the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California and the SPring-8 facility in Japan. These advanced X-ray sources allowed the team to capture real-time atomic-level images of the material during its transition between states. The X-ray pulses essentially acted as a camera, taking rapid “snapshots” of the material as it underwent its transformation, revealing intricate details about the atomic structure of the material.

The setup for these experiments included a series of pump-probe measurements. The researchers would “pump” or excite the material with an ultrafast laser pulse, then immediately “probe” its reaction using high-energy X-rays. These complementary techniques — which allow scientists to study the material in ultra-high detail and resolution — gave the team the ability to observe the state of the material at various stages of its transformation, spanning timescales from trillionths of a second to millionths of a second.

The “Soup Phase” and the Emergence of Supercrystals

The material underwent a dramatic transformation just moments after being excited by the laser. Within a trillionth of a second, a chaotic “soup phase” emerged in the material. During this period, the originally structured vortices of the material became disordered, resulting in a hot, chaotic mix of charged particles. As time progressed, the system began to cool, and order gradually started to emerge, similar to the way sugar crystals form out of a hot sugar solution.

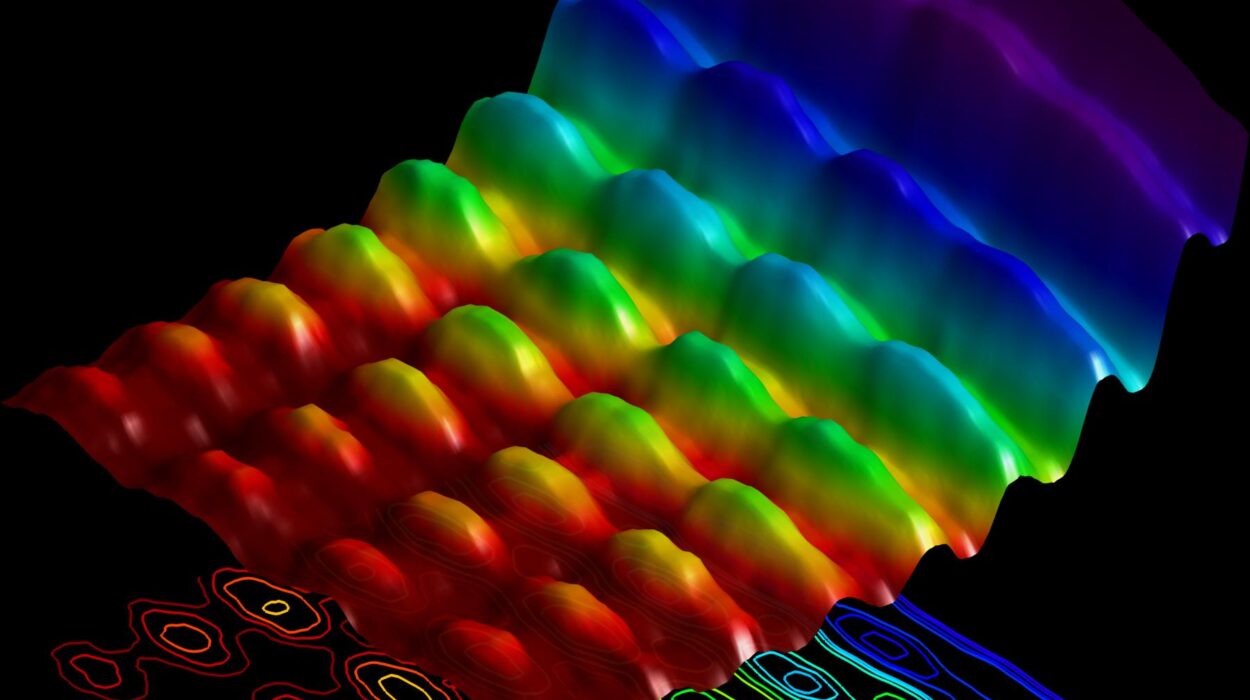

By about one nanosecond after the laser pulse, the material began to form a new, highly ordered structure: a supercrystal. This supercrystal was remarkable in that it was made of many smaller crystals aligned in a highly organized configuration, unlike its initial disordered state. What’s most fascinating about this finding is that the material achieved greater order in its final state than in its original state. This is not a common occurrence in experiments involving metastable states, which often result in materials that decay into more disordered configurations.

Researchers were able to track the growth and evolution of the supercrystal structure using X-ray mapping techniques. By imaging the sample before and after the transition, they were able to create highly detailed three-dimensional maps of the material. The collaboration with Argonne’s Advanced Photon Source played a crucial role in capturing these three-dimensional images, which provided a deeper understanding of the material’s transformation.

Implications for Future Technology and Materials Design

Understanding how metastable states emerge and evolve has significant implications for the design of future materials, particularly in the fields of microelectronics and data storage. Metastable states might be used to store information in ways that go beyond traditional binary logic. By harnessing the power of these unusual electronic landscapes, scientists could potentially design materials capable of more complex data encoding and faster information processing. This research could play an essential role in pushing the boundaries of Moore’s Law, which predicts the increasing density of transistors in integrated circuits.

As information technology moves toward its physical limits, researchers are eager to discover new mechanisms by which to store, manipulate, and process information more efficiently. Metastable materials offer exciting possibilities. For instance, their ability to exist in stable configurations beyond the norm could create opportunities for storing data in highly dense, multi-dimensional states.

Venkatraman Gopalan, a key researcher involved in the study, emphasizes the importance of finding new building blocks that could fuel faster information processing. He explains, “Length scales for microelectronics are reaching a certain limit, and there’s an urgent need to search for new building blocks to process information faster and represent it with higher density.”

The immediate future of this research lies in understanding the roles of different phases, like the soup phase, in enabling the material’s transition into metastable states. There is much to be learned from these transitions, which could ultimately inform the design of next-generation electronic devices with previously unimaginable capabilities.

Conclusion: Unlocking the Power of Metastability

The work conducted by the team at Argonne National Laboratory is just the beginning of what could become a profound new direction in material science. The study of metastable states and their transition under the influence of light has the potential to unlock a new class of materials with unprecedented electronic properties. Such advancements could usher in an era of faster, more efficient microelectronics, radically altering how information is stored, processed, and transmitted. As the science of metastability evolves, it will undoubtedly lead to innovations that could have a transformative impact on technology, industry, and society as a whole.

Reference: Vladimir A. Stoica et al, Non-equilibrium pathways to emergent polar supertextures, Nature Materials (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41563-024-01981-2