In the first few microseconds after the Big Bang, when the universe was nothing but a seething ocean of energy and fundamental particles, unimaginable processes were unfolding. For decades, scientists have wondered whether some of that raw chaos could have collapsed into black holes—dense objects so powerful that not even light can escape their pull. These hypothetical objects, called primordial black holes, have remained an elegant idea but without evidence.

Now, thanks to the piercing eyes of the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), humanity may be witnessing the first sign that such exotic relics of creation truly exist. And if confirmed, this discovery could force scientists to rethink one of the most fundamental assumptions about how black holes and galaxies come to be.

The James Webb Telescope and the Little Red Dots

Launched in December 2021, JWST was designed to look farther into space—and deeper into the past—than any telescope before it. Its powerful infrared instruments can capture light that has traveled across billions of years, carrying with it stories from the universe’s youth.

Recently, JWST detected a collection of faint, reddish smudges scattered across the distant cosmos. These have been nicknamed Little Red Dots (LRDs). At first glance, they looked like tiny baby galaxies, barely formed and dimly glowing. But on closer inspection, their light told a stranger, more compelling tale.

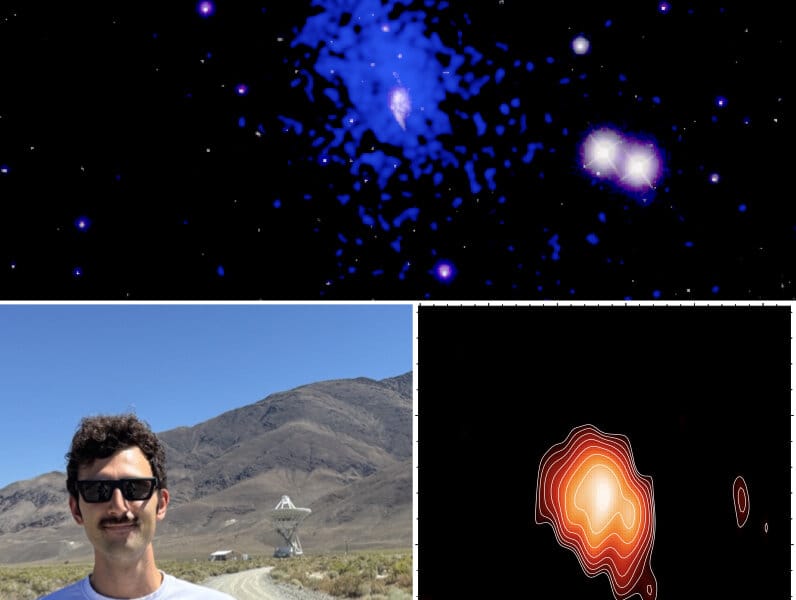

An international team led by astrophysicist Ignas Juodžbalis of the University of Cambridge focused on one of these objects, designated QSO1. What they found hidden in this faint red dot has stunned the scientific community.

A Monster in Miniature

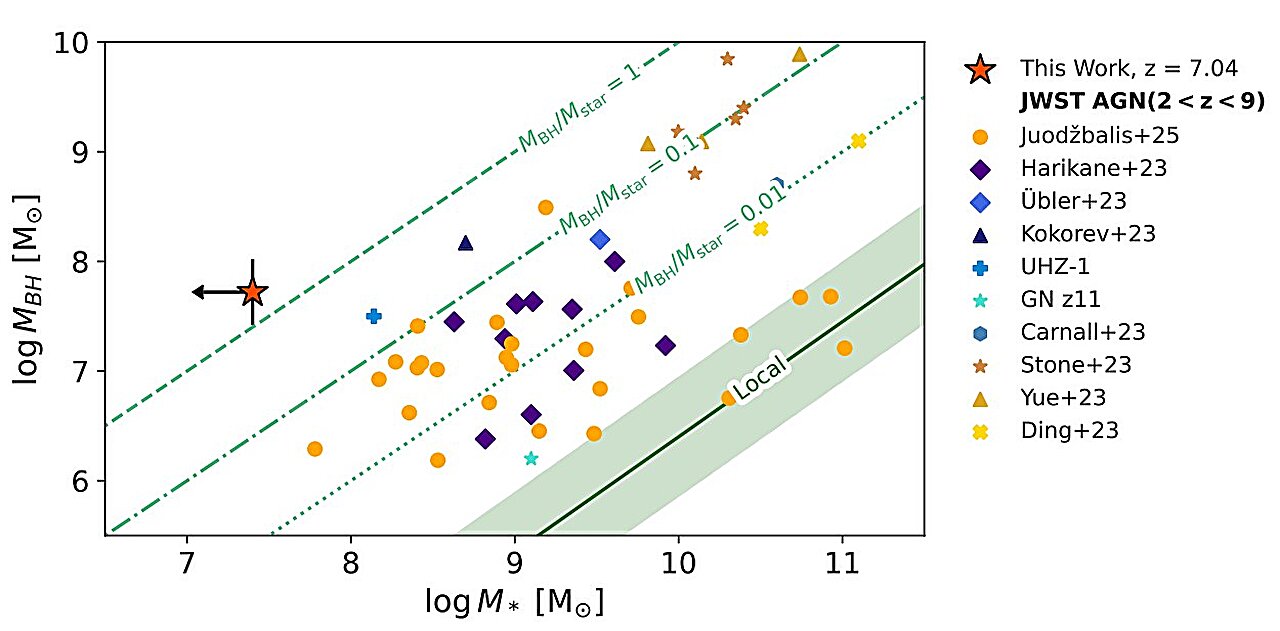

The team measured the light from QSO1 and discovered that it is powered by a black hole with the mass of about 50 million suns. This alone is startling, because the host galaxy in which this black hole resides appears tiny by comparison.

Typically, astrophysicists expect that galaxies come first. Stars gather into large structures, and then, over millions of years, gas funnels into their centers, where black holes slowly grow. But QSO1 flips that logic upside down. The black hole there is already massive, while the galaxy itself is barely developed.

Even more peculiar, this black hole seems to be nearly naked. Unlike the enormous quasars we usually observe, which blaze with the light of matter spiraling into their depths, QSO1 has only a small halo of material falling into it. For something so young and so massive, its stripped-down appearance makes no sense—unless we are seeing a completely different kind of black hole.

A Challenge to Conventional Wisdom

For decades, the narrative of cosmic growth has been fairly clear: galaxies form, stars ignite, and at their cores, black holes accumulate and expand. But the finding from QSO1 hints at a radical alternative: perhaps, in some cases, black holes came first, helping to shape the galaxies around them rather than waiting for galaxies to evolve.

This possibility is not only bold but also strangely familiar. In the 1970s, the legendary physicist Stephen Hawking predicted that primordial black holes might have formed in the immediate aftermath of the Big Bang. These would be objects born not from collapsing stars, as most black holes are, but from the raw density fluctuations in the newborn cosmos itself.

If the black hole in QSO1 is truly primordial, it would be the first tangible evidence of Hawking’s idea. It would mean that black holes are not merely the end stages of dying stars but also potential seeds of creation, shaping galaxies before galaxies could even exist on their own.

The Glow of Accretion

QSO1’s black hole is currently in the early stages of accretion, the process by which it pulls in gas and dust from its surroundings. As matter falls inward, it heats up and radiates energy, producing the mysterious glow that JWST detected. The brightness of this glow allowed scientists to measure the black hole’s size and confirm its enormous mass.

What is astonishing, however, is how little material seems to surround it. For a black hole this massive, one would expect a galaxy bustling with stars and dense clouds of gas. Instead, QSO1’s galaxy seems fragile, like scaffolding around a structure that has already been built. The black hole is the centerpiece, and the galaxy is the latecomer.

Black Hole Primacy

The team’s paper describes this phenomenon as “black-hole primacy.” It suggests that some black holes may form and grow earlier, or much faster, than the galaxies they inhabit. This flips the cosmic script: instead of galaxies nurturing black holes, black holes might help create galaxies by influencing how gas and stars collect around them.

If this idea holds true, it could explain how supermassive black holes, weighing billions of solar masses, managed to appear so quickly in the young universe—an unsolved puzzle that has long troubled cosmologists.

What Comes Next

For now, this discovery is just the first step. The QSO1 black hole is a tantalizing hint, not yet definitive proof. Scientists will need to measure the masses of many more Little Red Dots and distant quasars to see whether QSO1 is a rare anomaly or part of a much larger pattern.

If additional evidence emerges, the implications will be extraordinary. Not only would we confirm the existence of primordial black holes, but we would also have to rethink the relationship between black holes and galaxies, rewriting the story of cosmic evolution itself.

The Human Side of Discovery

Behind every headline-making finding is the quiet, relentless work of scientists who dare to ask questions bigger than themselves. This discovery represents decades of preparation, from building the James Webb Space Telescope to training researchers who could interpret its data. It is a testament to human curiosity—the same curiosity that once made Stephen Hawking wonder about the universe’s first black holes nearly half a century ago.

There is something deeply emotional about the possibility that, through JWST, we are looking back across billions of years and witnessing one of the universe’s first experiments in creating structure. The idea that a black hole, a symbol of destruction in popular imagination, could also be a cradle for galaxies gives us a profound reminder: the universe is rarely what we expect, and it is always more creative than we can imagine.

A Universe Waiting to Be Understood

Whether QSO1 proves to be a primordial black hole or simply a cosmic oddity, it has already reshaped how scientists think about the early universe. It has opened the door to questions that go beyond physics and astronomy, reaching into philosophy and wonder: How did order emerge from chaos? How many other black holes are out there, waiting to be seen? And could it be that the first architects of galaxies were not stars, but black holes themselves?

The answers are still being written in the starlight that travels across time to our telescopes. Each discovery is another piece of a puzzle that spans billions of years and countless galaxies. And with JWST’s gaze, we are closer than ever to completing that cosmic picture.

For now, we stand at the edge of a revelation. A nearly naked black hole, glowing faintly at the dawn of time, may be whispering to us a new story of creation—one where black holes were not just the monsters of the cosmos, but also its first architects.

More information: Ignas Juodžbalis et al, A direct black hole mass measurement in a Little Red Dot at the Epoch of Reionization, arXiv (2025). DOI: 10.48550/arxiv.2508.21748