For most of human history, the night sky seemed timeless. Stars appeared fixed, planets moved predictably, and comets occasionally flared across the heavens. But in the last decade, astronomers have confirmed something extraordinary: objects from other star systems have passed through our solar neighborhood, carrying with them secrets from worlds we may never reach.

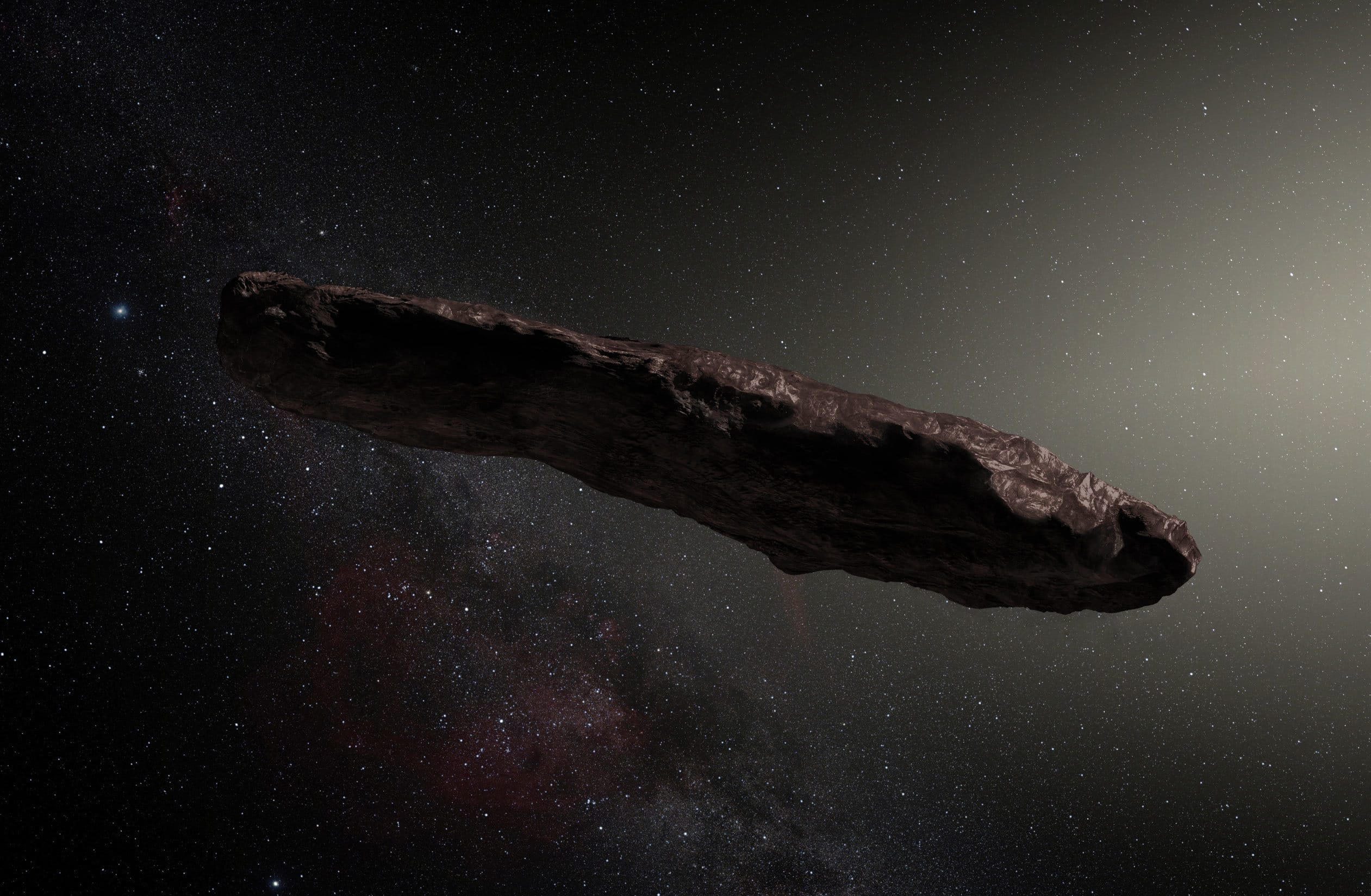

In 2017, the discovery of a mysterious, elongated body named ‘Oumuamua captured global attention. Just two years later came 2I/Borisov, a comet so pristine it seemed like a time capsule from another planetary nursery. And in July 2025, astronomers welcomed the arrival of 3I/ATLAS, a third interstellar visitor, this one clearly venting water vapor as it warmed under the sun’s light.

Three such detections in less than a decade overturned centuries of assumptions. Interstellar objects (ISOs), once purely theoretical, are now known to be real—and more common than we dared imagine. Each one is like a message in a bottle drifting across the cosmic ocean, offering a tangible sample of material from distant star systems.

Why Interstellar Objects Matter

Asteroids and comets are the leftover building blocks of planets. Studying our own gives astronomers a way to reconstruct the story of how the solar system formed. But ISOs provide something even more profound: a chance to examine the raw ingredients from other stars.

As Harvard researcher Shokhruz Kakharov explained, before ‘Oumuamua’s discovery we had “no direct evidence” that such travelers could reach us. Their arrival now allows scientists to study the chemistry and physics of alien planetary systems without sending spacecraft across interstellar distances. Each ISO carries with it not only the story of its own system’s formation, but also the signature of its long journey through the Milky Way.

They are also natural probes of galactic dynamics. Their paths through the stars record the gravitational tugs and pulls that shape the galaxy over billions of years. By retracing those paths, astronomers can peer into the history of stellar populations and planetary systems scattered across the Milky Way.

Origins Across the Galaxy

In a recent study, Kakharov and his mentor Prof. Abraham Loeb set out to answer a deceptively simple question: where did these visitors come from?

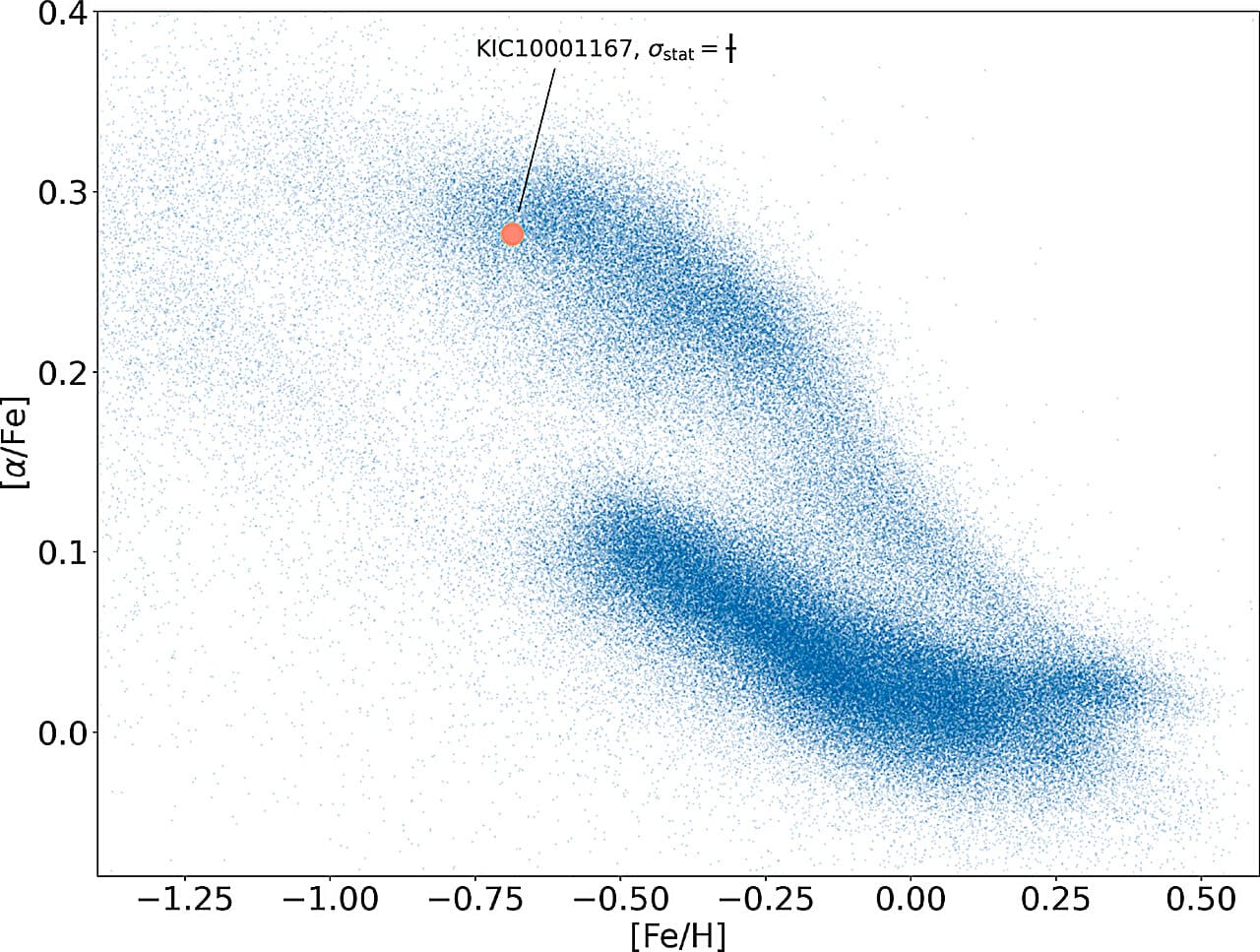

Using powerful computer simulations, they tracked the orbits of ‘Oumuamua, Borisov, and ATLAS backward through time. Because even tiny measurement uncertainties grow enormous over billions of years, they employed a statistical approach—running 10,000 possible trajectories for each object using a detailed model of the Milky Way’s gravitational field.

The results were striking.

- 3I/ATLAS, the most recent arrival, appears to be the oldest: about 4.6 billion years, roughly the age of the solar system itself. It likely originated from the thick disk of the Milky Way, a region populated by ancient stars with lower metal content.

- 1I/‘Oumuamua is comparatively young, about 1 billion years old, and came from the galaxy’s thin disk, where star formation is ongoing.

- 2I/Borisov falls in between, about 1.7 billion years old, also originating from the thin disk.

This diversity suggests ISOs are not rare flukes from young planetary systems but are ejected throughout the galaxy’s history. Each stellar generation seems to toss some of its icy or rocky fragments into the galactic tide, where they wander for eons before crossing paths with another star system—like ours.

The Mystery of ‘Oumuamua

Among the three, ‘Oumuamua remains the most enigmatic. Unlike Borisov and ATLAS, which clearly displayed comet-like activity, ‘Oumuamua showed no obvious tail. Instead, it behaved in puzzling ways—accelerating slightly as if pushed by something beyond gravity, while its shape appeared elongated or even flattened, depending on interpretations.

Some explanations involve exotic ices releasing gas invisibly, while others propose more unusual scenarios. Loeb himself famously suggested it could even be artificial, a piece of alien technology like a light sail. While most astronomers favor natural explanations, the debate underscored just how mysterious these objects can be—and how much we have yet to learn.

Natural Probes of Other Worlds

Unlike spacecraft, which take decades to travel even to nearby stars, ISOs come to us. They are ejected during the violent early days of planetary formation, when giant planets scatter leftover debris into interstellar space. Some are thrown outward with such speed that they escape their home systems entirely. After drifting for millions or billions of years, a lucky few intersect the solar system, giving us fleeting opportunities to study them.

In this sense, ISOs are free interstellar missions, delivering samples of exoplanetary systems without the cost or wait time of building starships. They show us what other planetary nurseries are made of, whether icy, rocky, or something entirely unfamiliar.

The Promise of Future Discoveries

Until recently, the discovery of an ISO felt like a once-in-a-lifetime event. But with the upcoming Vera C. Rubin Observatory, that may soon change. Its Legacy Survey of Space and Time (LSST) will scan the sky every few nights with unprecedented sensitivity, potentially detecting dozens of ISOs each year.

Meanwhile, missions like the European Space Agency’s Comet Interceptor could one day fly out to meet one directly, capturing images and measurements as it speeds through the solar system. Such encounters could revolutionize planetary science, offering laboratory-like detail on material forged in alien suns.

A Galaxy of Wanderers

What makes the study of ISOs so profound is not just the science they carry, but the story they tell about our place in the universe. Each object is a traveler older than human civilization, older than Earth’s continents, sometimes even older than the sun itself. They remind us that the Milky Way is not static but dynamic, alive with motion and exchange.

When ‘Oumuamua was first spotted, astronomers described it as a messenger from afar. With Borisov and ATLAS following behind, it is clear that the galaxy is full of such messengers—cosmic drifters that bind star systems together into a greater story.

As we await the next visitor, we are left with the humbling realization that the universe is not distant and untouchable. Sometimes, it comes to us—bearing silent gifts from other worlds, waiting for us to notice, to measure, and to wonder.

More information: Shokhruz Kakharov and Abraham Loeb, Galactic Trajectories of Interstellar Objects 1I/’Oumuamua, 2I/Borisov, and 3I/Atlas. lweb.cfa.harvard.edu/~loeb/SL_25.pdf