Consciousness is the most intimate experience of our lives, and yet it is also the greatest mystery. Every thought, every memory, every sensation of joy or sorrow arises within the field of awareness we call the mind. We know what it is like to be conscious—we wake in the morning to the flood of perceptions and emotions, and we drift into unconsciousness at night when we sleep—but when we ask what consciousness actually is, the answers vanish like mist in sunlight. Scientists, philosophers, and spiritual thinkers have struggled for centuries with a deceptively simple question: is consciousness nothing more than the product of brain activity, or does it arise from a deeper origin beyond the reach of biology?

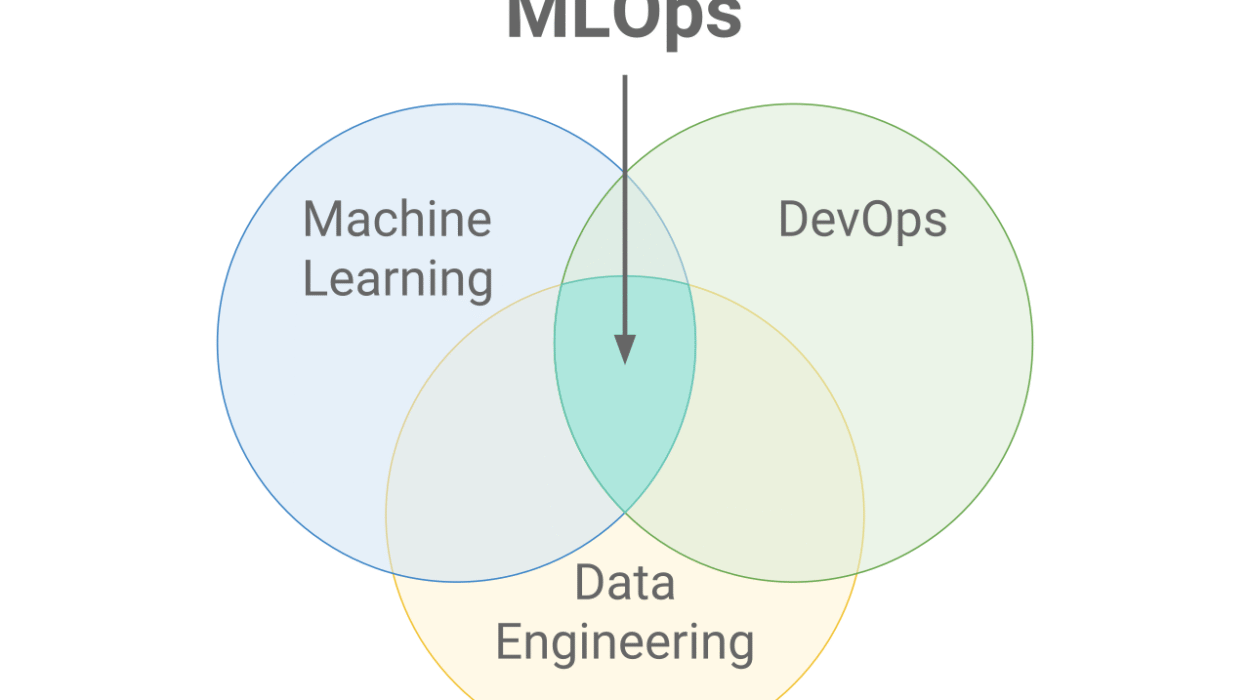

The debate is not merely academic. It touches on the essence of human identity and the meaning of existence. If consciousness is reducible to neurons and electrical impulses, then it may be explained entirely by physics and chemistry. If, however, consciousness has roots in some deeper layer of reality, then our minds may be windows into a universe far more mysterious than we can imagine. The search for an answer brings us to the intersection of neuroscience, philosophy, quantum physics, and metaphysics—a crossroads where science and wonder converge.

The Brain as the Engine of Mind

Modern neuroscience has made astonishing progress in tracing the workings of the brain. Sophisticated imaging technologies such as fMRI and PET scans allow scientists to watch the living brain in action, revealing networks of neurons firing in patterns as people think, feel, and perceive. Certain regions light up when we solve a mathematical problem, others when we recall a memory or listen to music. Injuries to particular areas can disrupt speech, vision, or emotion, demonstrating a clear link between brain structure and conscious experience.

On the surface, this evidence seems compelling. Billions of neurons, each communicating with thousands of others across synapses, form vast circuits of electrical activity. From these networks emerge patterns—waves of activity in the cerebral cortex, oscillations across hemispheres—that correlate with awareness. When the brain is under anesthesia, these patterns collapse, and consciousness fades. When brain cells die in the final moments of life, awareness vanishes entirely. To many scientists, the conclusion is straightforward: consciousness is an emergent property of brain activity, much as the wetness of water arises from the interaction of hydrogen and oxygen atoms.

This view, known as physicalism or materialism, has dominated scientific thinking for decades. It rests on the assumption that everything in the universe, including the mind, can ultimately be explained by physical processes. Yet while this framework has yielded extraordinary insights into the mechanics of cognition, it still faces a profound puzzle—one that no amount of brain imaging has resolved.

The “Hard Problem” of Consciousness

The philosopher David Chalmers famously distinguished between the “easy problems” of consciousness and the “hard problem.” Easy problems are not trivial, but they involve questions that can be addressed by studying brain function: how we process visual input, how memory is encoded, or how language is generated. The hard problem, by contrast, asks why all this activity should be accompanied by subjective experience. Why does the firing of neurons produce the feeling of pain, the redness of a sunset, or the sweetness of a melody?

This difficulty is not just semantic—it exposes a gap in our understanding. Brain science can map correlations between neural states and mental states, but correlation is not causation. Explaining how neural activity leads to behavior is one thing; explaining why it feels like something to be that organism is another. The gap between physical description and subjective experience has led some thinkers to suggest that consciousness might not be reducible to matter alone.

Consciousness as an Emergent Phenomenon

One influential approach argues that consciousness emerges when physical systems reach a certain level of complexity. Just as the properties of a hurricane cannot be reduced to the movements of individual air molecules, or the behavior of an ant colony cannot be predicted from studying a single ant, so too consciousness might emerge from the collective dynamics of billions of neurons. According to this view, once the brain reaches a critical threshold of complexity and connectivity, awareness arises naturally.

The appeal of emergence lies in its ability to preserve physicalism while acknowledging that higher-level phenomena can display properties absent from their individual parts. Yet critics argue that emergence still does not bridge the explanatory gap. Complexity can produce novel behaviors, but it does not explain why these behaviors should be accompanied by inner experience. A sufficiently complex machine might process information, but why should that information be felt? The mystery of subjectivity lingers unresolved.

Quantum Theories of Mind

Another line of thought ventures beyond classical neuroscience into the realm of quantum physics. The brain is often treated as a biological machine, yet at its foundation it is composed of particles governed by quantum mechanics—the same laws that describe the strange behavior of electrons, photons, and atoms. Some researchers have speculated that consciousness itself may be a quantum phenomenon, arising not from conventional neural networks but from quantum processes within the brain’s microstructures.

One of the most notable proposals is the Orch-OR (Orchestrated Objective Reduction) theory, developed by physicist Roger Penrose and anesthesiologist Stuart Hameroff. They suggest that quantum computations occur within microtubules—tiny structural components of neurons—and that these computations give rise to conscious awareness. While controversial, this theory attempts to connect the mystery of consciousness with the fundamental indeterminacy of quantum mechanics, where observation appears to collapse possibilities into actuality.

Skeptics argue that the brain is too warm, wet, and noisy for delicate quantum states to survive, though recent research has hinted that biological systems such as photosynthesis may indeed exploit quantum effects. Whether or not quantum theories prove correct, they reflect a deeper intuition: that consciousness may not be adequately explained within the framework of classical physics.

Panpsychism and the Idea of Universal Mind

If consciousness cannot be fully reduced to brain activity, perhaps the problem lies in assuming that consciousness emerges only at high levels of complexity. Panpsychism, an ancient idea revived in modern philosophy, suggests that consciousness is a fundamental property of the universe, present in all matter to varying degrees. According to this view, the human mind is not an isolated miracle but a flowering of awareness already latent in the fabric of reality.

For panpsychists, even the simplest particles might have rudimentary forms of proto-consciousness. As matter organizes into more complex systems, these seeds of awareness combine and integrate, eventually giving rise to the rich inner worlds of animals and humans. While this idea may seem radical, it avoids the problem of explaining how consciousness suddenly appears from non-conscious matter. Instead, it reframes the universe as inherently imbued with mind-like qualities.

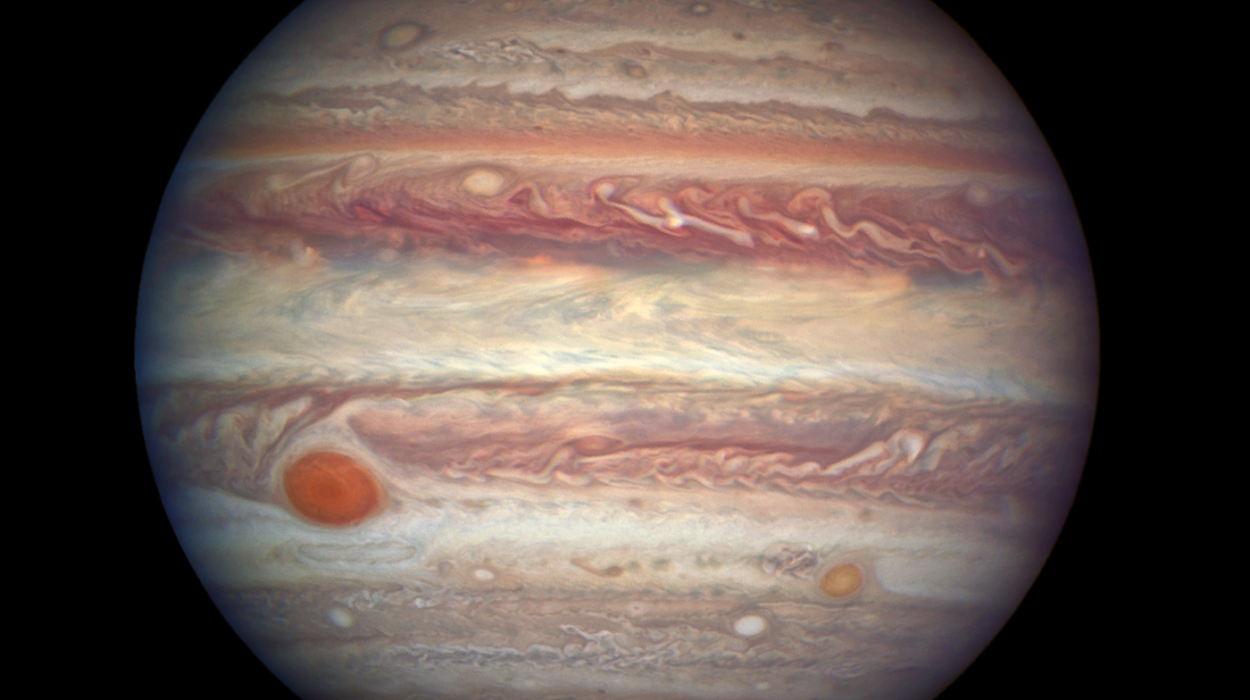

Critics counter that panpsychism risks diluting the concept of consciousness to meaninglessness. If everything is conscious, what distinguishes human experience from the “consciousness” of a rock? Defenders reply that degrees and forms of consciousness vary widely, just as heat exists in both a flickering candle and the heart of a star. The debate remains unresolved, but panpsychism’s revival signals a growing recognition that purely mechanistic explanations may not suffice.

Eastern Philosophies and the Primacy of Awareness

Beyond Western science and philosophy, many Eastern traditions have long held that consciousness is not a byproduct of matter but the foundation of reality itself. In Vedanta, for instance, consciousness (Atman) is seen as identical with the ultimate ground of existence (Brahman). Buddhist teachings emphasize awareness as the ever-present backdrop against which all thoughts and sensations arise and pass away.

These traditions suggest that consciousness is not created by the brain but revealed through it, much as a radio does not create music but tunes into signals already present. In this analogy, the brain is an instrument, and consciousness is the underlying field it channels. While such views cannot be tested in the same way as neuroscientific hypotheses, they resonate with subjective experience and provide a radically different framework for understanding the mind.

The Brain as Filter, Not Generator

An idea that bridges scientific and spiritual perspectives is the filter theory of consciousness. Rather than producing awareness, the brain may act as a filter or limiter, narrowing a vast field of universal consciousness into the focused experience necessary for survival. Aldous Huxley, drawing on the philosopher Henri Bergson, described the brain as a “reducing valve,” restricting the flood of awareness so that we are not overwhelmed.

This view has gained renewed interest from research into altered states of consciousness, whether through meditation, psychedelics, or near-death experiences. In such states, individuals often report a sense of expanded awareness, unity with the cosmos, or timelessness—experiences that suggest the brain may ordinarily constrain consciousness, and that under certain conditions, those constraints loosen. While such reports are subjective, they raise provocative questions about whether the brain is the origin of mind or simply its local expression.

The Ethical and Existential Stakes

Why does it matter whether consciousness arises solely from the brain or has a deeper origin? The implications are profound. If the mind is nothing more than neural circuitry, then death is the absolute end of subjective experience. The richness of consciousness is extinguished when the brain ceases to function. While this view may seem bleak, it emphasizes the preciousness of life and the urgency of making meaning within our finite existence.

If, however, consciousness is more than the brain—if it is fundamental, universal, or capable of existing beyond physical death—then our understanding of reality and our place within it must be reimagined. Such a perspective opens the door to spiritual interpretations, to the possibility of continuity beyond bodily demise, and to a vision of the universe not as cold and indifferent but as intrinsically alive with awareness.

Either way, the question forces us to confront who we are and what it means to exist. Are we temporary patterns in neural networks, or are we participants in a deeper mystery woven into the fabric of the cosmos?

Toward an Integrated Understanding

The search for answers need not force a choice between science and spirituality. Rather, it may call for a synthesis in which empirical investigation and contemplative insight inform one another. Neuroscience can continue to map the correlations between brain activity and experience, while philosophy and contemplative traditions probe the nature of awareness itself.

Already, interdisciplinary fields such as neurophenomenology seek to combine first-person reports of experience with third-person brain data, acknowledging that consciousness cannot be fully understood from the outside alone. Advances in artificial intelligence, too, challenge us to define what it would mean for a machine to be conscious, pushing the boundaries of our definitions.

Perhaps the ultimate truth will transcend current categories. Consciousness may be both emergent and fundamental, both shaped by the brain and connected to a deeper ground of being. Just as light is both particle and wave, perhaps mind is both product and source, a paradox that defies reduction to a single explanation.

Conclusion: The Light Behind the Eyes

In the end, the mystery of consciousness is inseparable from the mystery of existence itself. Each of us carries within our own awareness the very phenomenon we seek to explain. Every time we wonder about the origins of consciousness, we do so through consciousness itself—an infinite loop in which the questioner and the question are one.

Whether science eventually explains consciousness as the natural consequence of brain activity, or whether it discovers that awareness has a deeper origin, the journey itself reveals the profound wonder of being alive. To feel, to know, to ask—these are not trivial accidents of biology but the very essence of what it means to be human.

Einstein once remarked that the most incomprehensible thing about the universe is that it is comprehensible. Consciousness is what makes that comprehension possible, the light behind the eyes that transforms matter into meaning. Its origins may remain hidden, but its reality is undeniable.

Perhaps the greatest truth is not whether consciousness arises from the brain or from a deeper source, but that in this fleeting moment of existence, we are conscious at all. That simple fact is both miracle and mystery, grounding us in the knowledge that to be aware is to participate in the vast and unfinished story of the cosmos itself.