More than 5,000 years ago, high in the shadowed corridors of the Italian Alps, a man died alone on a mountain pass. His body, battered by stone and arrow, was slowly consumed by snow and time. Yet unlike so many others lost to history, Ötzi the Iceman did not disappear. He froze, and he endured.

And now, millennia later, the story of Ötzi is expanding—not just as a mystery of how he died, but as a revelation of how we lived, evolved, and adapted. From his leathery skin to the copper axe found at his side, every part of Ötzi has told us something new about prehistoric life. But in a recent study, it’s his ribcage—yes, his ribs—that’s offering a stunning new chapter in our evolutionary tale.

Thanks to cutting-edge digital reconstructions, researchers have looked deep into the shape and structure of Ötzi’s chest. What they found reaches far beyond one man in the Alps—it helps decode the anatomy of all Homo sapiens and their ancient journey across climates, continents, and time.

The Shape of Breath: What the Ribcage Reveals

The ribcage is more than a cage for the lungs. It’s a vital architectural feature that supports breathing, posture, and protection for essential organs. Its shape can reflect biology, behavior, and even the weather patterns that ancient people lived through. When scientists examined Ötzi’s ribcage, they weren’t just seeing bones. They were reading a map of adaptation.

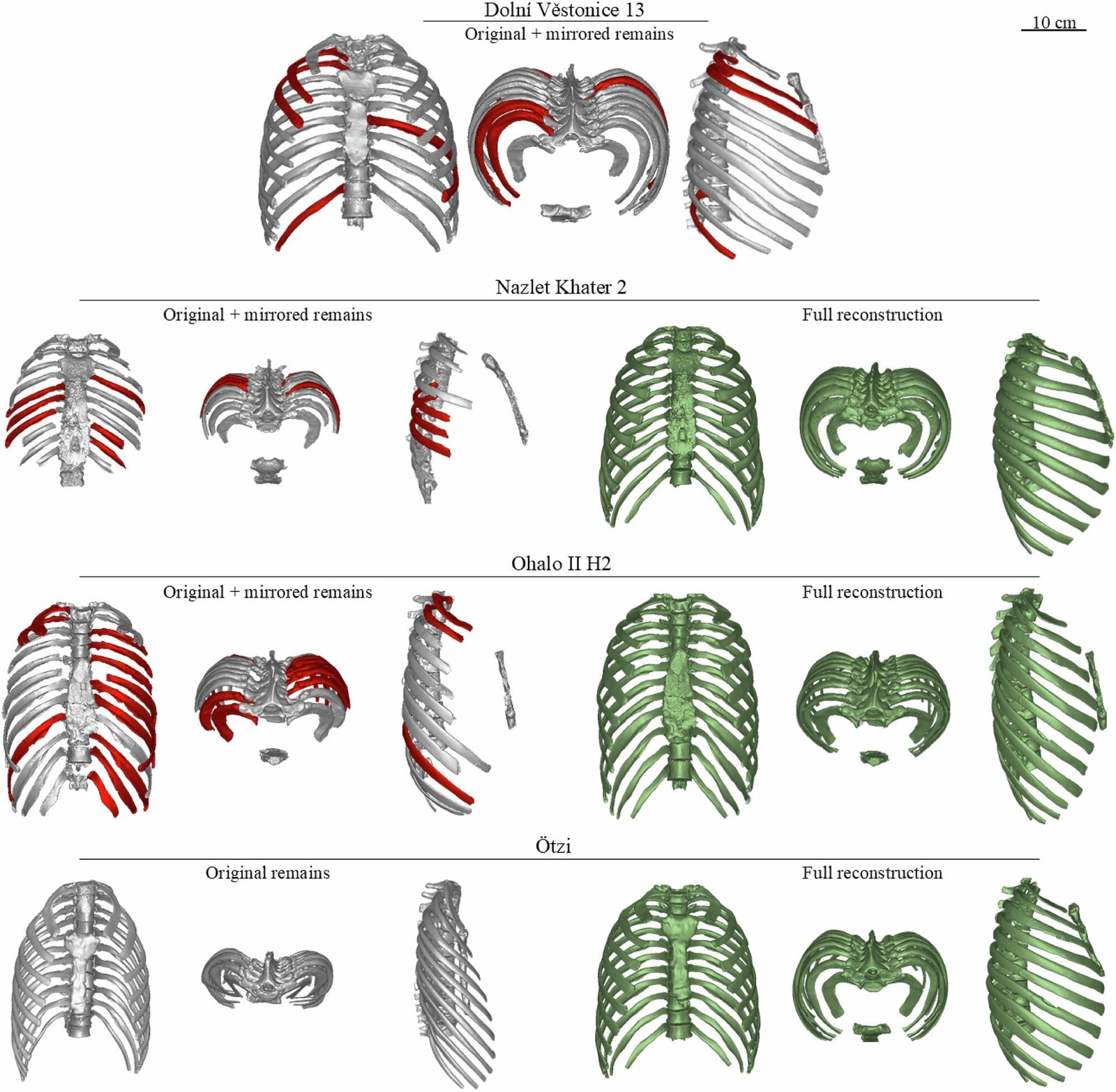

Led by José M. López-Rey of the National Museum of Natural Sciences in Madrid, a team of researchers digitally reconstructed the ribcages of four prehistoric humans. Alongside Ötzi, they examined Nazlet Khater 2 from Egypt (30,000 years old), Ohalo II H2 from Israel (19,000 years old), and Dolní Věstonice 13, unearthed in the chilly regions of the Czech Republic and dating back 30,000 years.

Each of these skeletons represented early Homo sapiens living in different climates and geographies. By comparing their 3D thoracic models with those of 59 modern humans—alongside Neanderthals and Homo erectus—the researchers were able to pose a provocative question: Is the slender, barrel-shaped ribcage seen in modern humans truly a unique evolutionary feature, or did it emerge from an ancient, shared design?

The Ghosts We Carry in Our Chests

Contrary to what many anthropologists long believed, the findings reveal that our “modern” ribcage shape—rounded, globular, slightly cylindrical—is not so modern after all. The fossilized ribcages of ancient Homo sapiens matched these shapes closely, suggesting that this thoracic structure was already established tens of thousands of years ago.

This discovery upends earlier assumptions that Homo sapiens evolved smaller, narrower chests only after Neanderthals died out. Instead, it appears that early modern humans already bore this hallmark structure, perhaps passing it down through countless generations.

But there’s more. The study uncovered another layer—climatic adaptation.

How Weather Wrote Our Skeletons

In the warmer, more temperate regions of ancient Egypt and Israel, early humans like Nazlet Khater 2 and Ohalo II H2 had narrower, more cylindrical ribcages. These chests would have supported efficient thermoregulation, allowing the body to shed heat more easily in hot environments.

Meanwhile, Dolní Věstonice 13, found in the cold plains of prehistoric Europe, had a broader, deeper ribcage—surprisingly similar in volume to those of robust Neanderthals and even early Homo erectus. These wider chests likely housed larger lungs and retained heat more effectively, offering an evolutionary advantage in frigid climates.

Ötzi, ever the transitional figure, fell somewhere in between. His ribcage blended features from both warm and cold-adapted populations, hinting at the unique challenges of Alpine life. His ancestors may have roamed across shifting climates, and his skeleton tells the tale of a body trying to do the same—anatomy shaped by the seasons.

Redrawing the Blueprint of Our Species

One of the study’s most profound insights is that there is no single “correct” or uniform human body plan. While it’s tempting to believe that evolution moves in a straight line from primitive to advanced, the story told by our ribcages is one of diversity, flexibility, and plasticity.

Dolní Věstonice 13, for instance, had a thoracic size that nearly rivaled that of Neanderthals, even though he was clearly Homo sapiens. This contradicts the long-standing idea that our species always had more slender, delicate bodies. Instead, it points to a dynamic truth: the human form has changed again and again, responding not just to genetics, but to the raw pressures of climate and environment.

The implications stretch far beyond bones. If climate could reshape our chests, what else might it have altered? Our muscle distribution? Metabolic rates? The way we moved, worked, even gave birth? Evolution, it turns out, is not a matter of fixed endpoints—it’s a dance of adaptation. And we are still dancing.

What Our Ancestors Still Teach Us

In examining the bones of Ötzi and his long-dead kin, scientists aren’t merely uncovering data. They are hearing echoes. Each rib, each curve, each subtle angle of a fossilized sternum whispers a story of endurance. These people weathered ice ages, deserts, hunger, migration, and injury. They didn’t have antibiotics or warm coats or nutrition labels. Yet they thrived long enough to pass their blueprints to us.

And here we are—sitting in climate-controlled homes, typing on machines, reading about our ancestors whose bodies told time with the wind and hunger with the seasons.

Understanding how their bodies evolved not only illuminates our past—it also helps us anticipate our future. In an era of rapid climate change, we’re once again facing environmental pressures. While we have technology on our side, our biology remains a product of ancient adaptations. By studying how our ribcages once responded to nature’s challenges, we may better understand how to navigate the ones that lie ahead.

A Living Archive Beneath the Skin

In Ötzi’s chest, a story has been locked in ice for 5,300 years. Not just a story of how he lived or died—but of how we came to be the humans we are today. His ribs are not just remnants of a man—they are a record of deep time, a survival guide written in bone.

This new research doesn’t just offer anatomical insight—it reveals the fluidity of our form, the dance between genes and geography, between biology and behavior. It reminds us that evolution isn’t finished. That even now, as our environment shifts, so too might our bodies—slowly, subtly, like snow reshaping a mountain.

Ötzi walked through an ancient world we can barely imagine. But through science, we can follow his footsteps—not with boots, but with curiosity. We don’t need time machines. We just need to look closer.

And listen to the bones.

Reference: José M. López-Rey et al, Fossil ribcages of Homo sapiens provide new insights into modern human evolution, Communications Biology (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s42003-025-08472-3