Somewhere beneath the warm, blue waters of Okinawa, an octopus flexes a soft, intelligent arm through the sands of the seafloor. Its world is fluid, shapeshifting, kaleidoscopic—a living dreamscape of textures, colors, and smells. And yet, in this alien world of silent hunting and seamless camouflage, something profoundly human has been discovered: the octopus can be tricked into believing a fake arm is its own.

This revelation doesn’t just astonish us—it challenges everything we thought we knew about the nature of self-perception, consciousness, and the mysterious link between mind and body. That a creature so evolutionarily distant from humans—an invertebrate with no spine, no bones, and a brain radically unlike ours—can fall for the same multisensory deception that fools people, mice, and monkeys suggests a deeper truth: the sense of body ownership may not be a uniquely human trait at all.

The Curious Case of the Rubber Hand

The rubber hand illusion is one of neuroscience’s most eerie and elegant experiments. First described in 1998 by Matthew Botvinick and Jonathan Cohen, it involves a strangely simple trick: hide a person’s real hand behind a screen, place a lifelike rubber hand in front of them, and stroke both hands simultaneously with a brush or a soft tool. Within seconds, the brain begins to merge sight and touch, convincing the person that the rubber hand is actually part of their body.

Participants often gasp when the rubber hand is suddenly struck or threatened. Their real hand may remain untouched, but the brain has already adopted the fake limb. This powerful illusion shows just how malleable our sense of self can be—and how easily the brain can be persuaded by synchronized sensory input.

Over the years, researchers have shown that this trick doesn’t just work on humans. Primates and rodents have also demonstrated responses that suggest a similar misattribution of bodily ownership. But octopuses? Their nervous systems are so radically different that the possibility seemed implausible—until now.

An Arm That Wasn’t Theirs—But Felt Like It

In a breakthrough study published in Current Biology, researchers Sumire Kawashima and Yuzuru Ikeda at the University of the Ryukyus designed a clever aquatic version of the rubber hand illusion. Their subjects were plain-body octopuses (Callistoctopus aspilosomatis), enigmatic creatures known for their problem-solving abilities, camouflage mastery, and famously distributed nervous systems. Unlike humans, octopuses have a significant portion of their neurons—more than two-thirds—distributed across their arms, each of which can move semi-independently and respond to stimuli without direct input from the central brain.

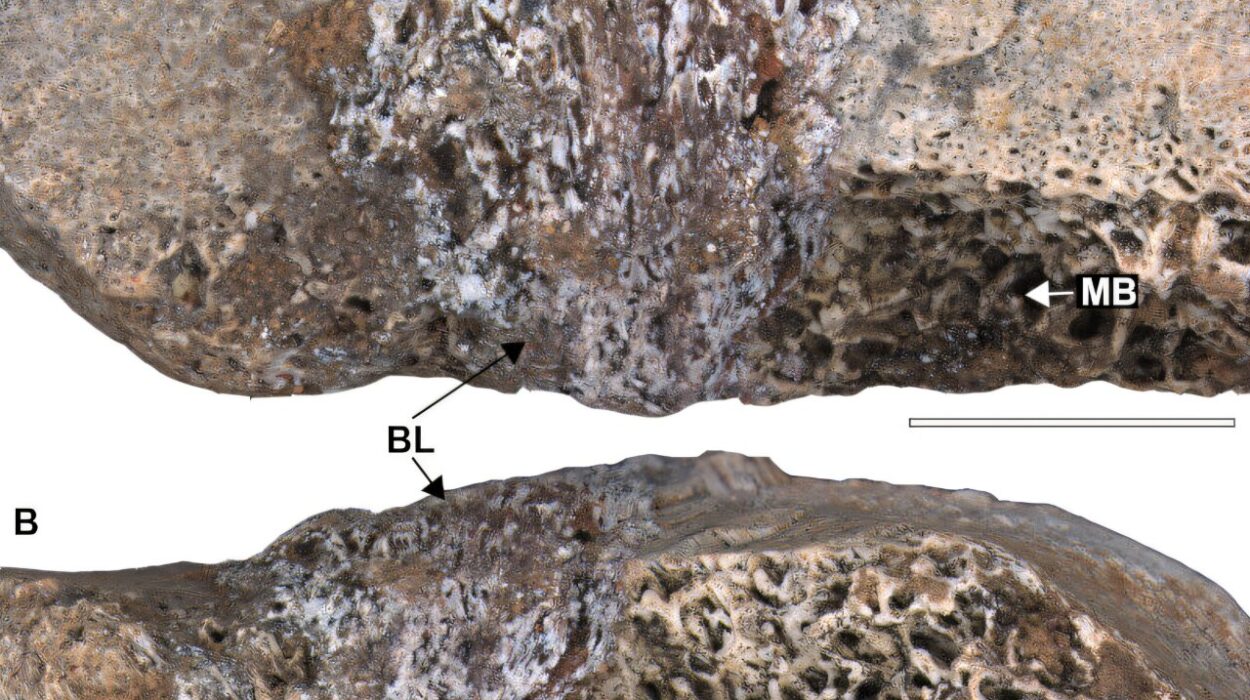

To test the illusion, the scientists placed a fake gel-like arm behind an opaque partition in a tank, directly above one of the octopus’s real arms. Both the real and fake limbs were stroked at the same time with soft plastic calipers. At first, the octopus remained calm. But then, when the fake arm was suddenly pinched with tweezers, the reaction was unmistakable. The animal flinched, changed color, pulled away, or jetted off—behaviors it typically uses in response to direct bodily threat.

Even without seeing its real arm, the octopus behaved as if it had felt the pinch on a limb that was, in fact, not its own. The implication? The octopus had adopted the dummy arm into its own body schema. It had been tricked into feeling ownership of something alien.

When the experiment was tweaked—either by removing the synchronized stroking, mismatching the fake arm’s appearance, or altering the rhythm—the illusion fell apart. No defensive response was observed. The octopus knew something was off. The magic of the illusion only worked when sight and touch harmonized in time.

An Alien Intelligence, A Familiar Illusion

What makes this discovery so profound is not just that octopuses can experience the rubber hand illusion—it’s how they do it. Octopuses evolved their intelligence entirely separately from vertebrates. Our common ancestor lived over 500 million years ago. Their neural architecture is distributed, decentralized, and unlike anything in the mammalian world. Their arms are like autonomous explorers, capable of learning, remembering, and reacting without waiting for commands from the brain.

And yet, in the midst of this decentralized nervous system, there is a mechanism—perhaps a perceptual unity—that allows them to feel ownership over a limb. It suggests that some form of integrated body representation, or “body schema,” exists in the octopus mind. And more astonishingly, it suggests that this ability may not require a vertebrate brain at all.

If this is true, it means the roots of bodily self-awareness run deeper than we thought. That the neural mechanisms required for the sense of body ownership may have evolved more than once—or perhaps emerged from even more ancient principles of sensory integration shared across the animal kingdom.

What Is the Self, After All?

The rubber hand illusion isn’t just a parlor trick for neuroscientists. It strikes at the very core of identity. To feel that your body is yours is one of the most basic—and deeply personal—elements of consciousness. When this sense fails, as in rare neurological conditions like asomatognosia, patients may deny that their limbs belong to them at all. They might stare at their own arm and say, “That’s not mine,” even as it moves at their command.

Such disorders highlight how fragile the sense of body ownership is. It is not hard-wired; it is constructed—moment by moment—by the brain’s ability to weave together signals from sight, touch, proprioception (the sense of position), and expectation. When this integration is disrupted, so too is the self.

That an octopus—an animal with no skeleton, no centralized control center, and no common evolutionary path with us—can also build and lose this same illusion reveals something astonishing: the experience of having a body may be a widespread phenomenon, not limited to creatures with spines, hands, or even brains as we understand them.

The Robot in the Mirror and the Octopus in the Tank

Understanding how the octopus is tricked by the rubber hand illusion may do more than satisfy our philosophical curiosity—it may reshape the future of technology. Insights into how animals integrate multisensory input to construct a sense of body ownership could inform the design of more sophisticated robots and AI systems. If we want machines to interact with the world with the same fluidity and self-coherence as biological organisms, they must understand—at least computationally—where they end and the world begins.

In robotics, body schema is critical. A machine that “knows” what parts belong to it can adapt more effectively to unpredictable environments, modify its actions in real time, and even experience “embodiment” in virtual or physical systems. Mimicking the octopus’s decentralized yet unified body experience could help create machines that are both flexible and self-aware—at least in a limited sense.

And for humans, the implications are equally compelling. Disorders of body ownership, like phantom limb pain, alien hand syndrome, and certain dissociative conditions, could benefit from a better understanding of how different brains—both human and non-human—construct the experience of self. Treatments might one day involve retraining the brain’s sensory integration systems using insights drawn from creatures of the deep.

What the Octopus Teaches Us About Being Alive

The octopus has always captured the human imagination. It is a creature of myth and marvel—a shapeshifter, an escape artist, an alien genius wrapped in soft skin and sinewy motion. But now, it may also be a philosopher of the flesh. Not by thought, but by sensation. Not by words, but by the quiet agreement between eye and nerve.

By falling for a trick that was never meant for them, octopuses have joined us in one of our most intimate illusions: the belief that what we see and feel is always real, always ours. That the boundary between body and world is stable. That we know what it means to be “me.”

In the quiet ripples of a lab tank in Okinawa, an octopus reached for a body that was not its own—and for a moment, believed it was. And in that moment, the distance between species collapsed. Two minds—one human, one cephalopod—met in the shared confusion of identity.

The illusion was fake. But the insight it gave us is very, very real.

Reference: Sumire Kawashima et al, Rubber arm illusion in octopus, Current Biology (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2025.05.017