More than 4.5 billion years ago, long before human minds could contemplate time itself, a cloud of cosmic dust and gas swirled in the vastness of a young solar system. The remnants of ancient stars, forged in supernova explosions, drifted and collided under the relentless pull of gravity. This chaotic dance slowly coalesced into a fiery, molten sphere—a newborn Earth.

The early planet was not the calm, life-sustaining world we know today. It was a hellscape of churning magma oceans, volcanic eruptions, and relentless bombardment from asteroids. The young Sun shone dimmer than it does now, yet the surface of Earth glowed from its own internal fury. There was no oxygen to breathe, no oceans to sail, and no continents to stand upon. Earth was a glowing ember in space, still finding its shape.

But even in these violent beginnings, the seeds of life were hidden. Heavy elements like iron sank toward the center, forming the planet’s core, while lighter materials floated outward to create the first crust. Water, delivered by icy comets and asteroid impacts, began to gather in basins. The foundation for oceans was being laid, even as the planet raged with heat.

The First Oceans and Atmosphere

As Earth cooled, a remarkable transformation unfolded. Water vapor released by countless volcanic eruptions condensed and fell as rain for millions of years. These torrential downpours filled the early basins, creating primordial oceans. The planet’s surface hardened into a thin, unstable crust that floated atop a molten mantle.

The atmosphere during this era was nothing like today’s life-sustaining mix of nitrogen and oxygen. Instead, it was a toxic brew of carbon dioxide, methane, ammonia, and hydrogen sulfide. To early sunlight filtering through this haze, the planet must have glowed with an alien shimmer. Yet this harsh environment set the stage for something miraculous: the emergence of life.

The Dawn of Life

Sometime around 3.8 billion years ago, in a world without plants, animals, or even oxygen, life began. The exact details remain one of science’s greatest mysteries. Perhaps it started near hydrothermal vents on the ocean floor, where mineral-rich water and chemical gradients provided the building blocks for self-replicating molecules. Perhaps lightning strikes or meteorites delivered essential organic compounds.

However it began, the first living organisms were incredibly simple—single-celled microbes that fed on the chemical energy in their environment. They lacked complex structures but possessed something revolutionary: the ability to copy themselves, adapt, and evolve.

These early microbes transformed Earth in ways invisible to the naked eye but profound over geological time. By consuming carbon dioxide and other chemicals, they altered the planet’s chemistry. Some evolved the ability to harness sunlight, developing photosynthesis. With this innovation, life began producing oxygen—a waste product at first, but one that would ultimately reshape the entire world.

The Great Oxidation Event

For hundreds of millions of years, Earth’s atmosphere remained oxygen-poor. Any oxygen produced by photosynthetic microbes quickly reacted with iron and other elements, locking it away in rocks. But around 2.4 billion years ago, this balance tipped. Oxygen began accumulating in the atmosphere in what scientists call the Great Oxidation Event.

This transformation was both catastrophic and liberating. To many existing life forms that had evolved in an oxygen-free world, the gas was toxic, leading to mass die-offs. Yet oxygen opened doors to more efficient energy use, paving the way for complex life. It also created the ozone layer, shielding the planet from harmful ultraviolet radiation and making shallow waters and land safer for living organisms.

The world’s appearance changed too. Iron oxidized in the oceans, settling to the seafloor and forming vast bands of red rock still visible today. The sky, once hazy, may have turned blue for the first time. Earth was becoming recognizable to our modern eyes, even as it remained entirely alien to future humans.

The Rise of Supercontinents

Earth’s surface was never static. The planet’s crust floated on a restless mantle, and over billions of years, this movement built and destroyed continents repeatedly. The first true supercontinent, called Kenorland, formed about 2.7 billion years ago. It eventually broke apart, only to be replaced by others, including Nuna, Rodinia, and Pannotia.

These colossal landmasses profoundly influenced life and climate. When continents clustered near the poles, ice sheets grew, plunging the planet into global freezes known as “Snowball Earth” episodes. During these periods, ice stretched from poles to near the equator, and oceans froze over. Life endured in isolated refuges beneath the ice, clinging to survival in what must have felt like a nearly dead world.

But Earth has always been dynamic. Volcanic activity and shifting plates eventually warmed the planet, melting the ice and triggering evolutionary bursts. New species flourished, and ecosystems became more complex. These cycles of assembly and breakup would continue, shaping the future of life countless times.

The Cambrian Explosion: Life Takes Center Stage

For billions of years, life remained microscopic. But around 540 million years ago, a dramatic evolutionary event transformed the biosphere—the Cambrian Explosion. In a relatively short span of geological time, an astonishing diversity of multicellular organisms appeared.

Oceans teemed with creatures unlike anything before: trilobites scuttled across the seafloor, spiny predators floated through the water, and the first primitive vertebrates emerged. Complex eyes evolved, transforming how organisms interacted with their environment. This explosion of innovation was fueled by rising oxygen levels, genetic breakthroughs, and ecological competition.

The Cambrian seas were a crucible for future life. Many of the fundamental body plans—limbs, shells, segmented bodies—that define today’s animals originated during this time. Evolution’s creativity was unleashed, setting the stage for future land colonization.

From Ocean to Land

For most of Earth’s history, life belonged to the oceans. But about 470 million years ago, plants and fungi began creeping onto land, forming the first primitive ecosystems. These early colonizers altered the planet dramatically. Roots stabilized soils, and photosynthesis drew carbon dioxide from the air, cooling the climate.

Animals soon followed. Insects scurried across the ground, and amphibians emerged from water to breathe air and hunt on land. Forests of towering ferns and giant horsetails spread, creating lush habitats. By 300 million years ago, massive swampy forests covered vast regions, laying down the coal beds that would one day fuel human industry.

Reptiles evolved from amphibians, adapting to life fully away from water. These early reptiles diversified into many forms, including the ancestors of dinosaurs and mammals. Earth was entering an age of giants and drama.

The Age of Dinosaurs

About 252 million years ago, a cataclysmic event known as the Permian-Triassic extinction nearly wiped out life on Earth. Over 90% of species vanished in what scientists call “The Great Dying.” Volcanic eruptions, climate shifts, and ocean anoxia devastated ecosystems.

From this devastation, a new chapter began: the rise of the dinosaurs. For over 180 million years, these remarkable creatures dominated land, sea, and air. From massive, long-necked sauropods grazing treetop leaves to fierce predators like Tyrannosaurus rex, dinosaurs diversified into forms both awe-inspiring and bizarre.

During this era, Earth’s continents were united in a supercontinent called Pangaea, surrounded by a vast global ocean. Over time, Pangaea fractured, drifting into separate continents, shaping the geography we recognize today.

Alongside dinosaurs, other creatures thrived. Birds evolved from small feathered dinosaurs, taking to the skies. Mammals, though small and nocturnal, quietly evolved traits that would one day allow them to inherit the Earth.

The Cataclysm That Changed Everything

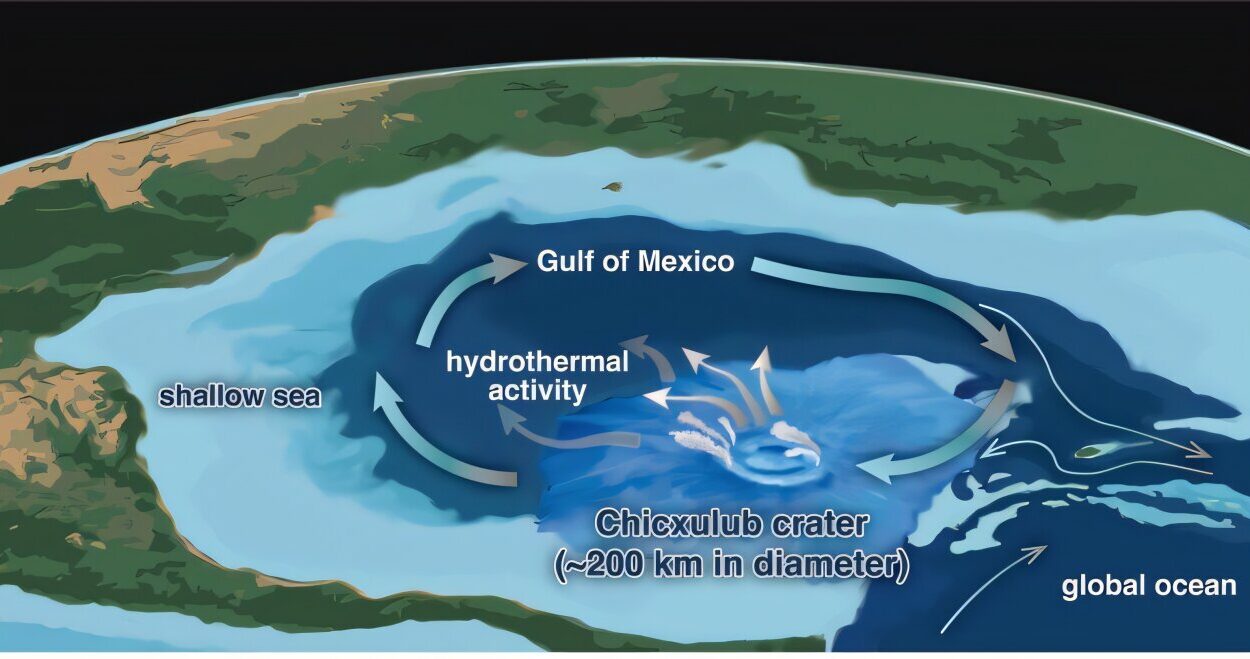

Sixty-six million years ago, life faced another catastrophe. A massive asteroid struck near present-day Mexico, unleashing energy billions of times greater than atomic bombs. The impact created wildfires, triggered tsunamis, and shrouded the planet in darkness. Dinosaurs, except for their bird descendants, vanished in the ensuing mass extinction.

Yet from this disaster, new possibilities emerged. With dominant dinosaurs gone, mammals rapidly diversified. Tiny, shrew-like creatures evolved into primates, whales, elephants, and countless other forms. Flowering plants spread, reshaping ecosystems. The modern world was taking shape.

The Rise of Humans

About 6 million years ago, in Africa, a lineage of apes began walking upright. These early hominins developed tools, learned to harness fire, and formed complex social groups. Over time, species like Homo habilis and Homo erectus spread across continents, adapting to diverse environments.

Roughly 300,000 years ago, Homo sapiens appeared—our species. With remarkable intelligence and language, humans built cultures, art, and technology. From small bands of hunter-gatherers, we transformed landscapes, domesticated plants and animals, and eventually formed civilizations.

In just a fraction of Earth’s history, humans became a geological force, altering climate, carving cities, and even venturing beyond the planet’s surface. We are a late arrival to Earth’s story, yet our impact is immense.

Earth in the Present and Future

Today, Earth is a vibrant, living planet—a blue jewel in space. Its continents drift slowly, mountains rise and erode, and ecosystems pulse with life. Yet it faces unprecedented challenges. Climate change, mass extinctions, and environmental degradation threaten the delicate balance that took billions of years to form.

But Earth is resilient. It has survived asteroid impacts, supervolcanoes, and ice ages. Life has repeatedly recovered, evolving in unexpected ways. The future will undoubtedly bring new transformations—whether shaped by humans or cosmic forces.

In billions of years, the Sun will swell into a red giant, boiling away oceans and possibly consuming the planet. Long before then, continents will shift again, new species will emerge, and Earth’s surface will be unrecognizable to us. Our planet’s story is far from over.

A Living Memory of Deep Time

As we gaze at mountains, oceans, and fossils, we are looking at chapters of a vast cosmic narrative. Every grain of sand was forged in ancient upheavals. Every breath we take carries echoes of primordial life. We are products of deep time, connected to microbes, dinosaurs, and distant stars.

The history of Earth is not just a record of rocks and organisms—it is a story of transformation, resilience, and wonder. From a fiery ball of molten rock to a cradle of conscious beings gazing at the universe, Earth’s journey is a testament to the extraordinary possibilities of nature.

We live in a brief moment of this grand tale, yet we are uniquely able to understand it. To know Earth’s history is to know ourselves, and to realize that the planet beneath our feet is not just home—it is a living memory of the cosmos, a miracle four and a half billion years in the making.